Joannes Gennadius

Joannes Gennadius (1844-1932) was born in Athens, the son of the distinguished George Gennadius and Artemis Benizelou.

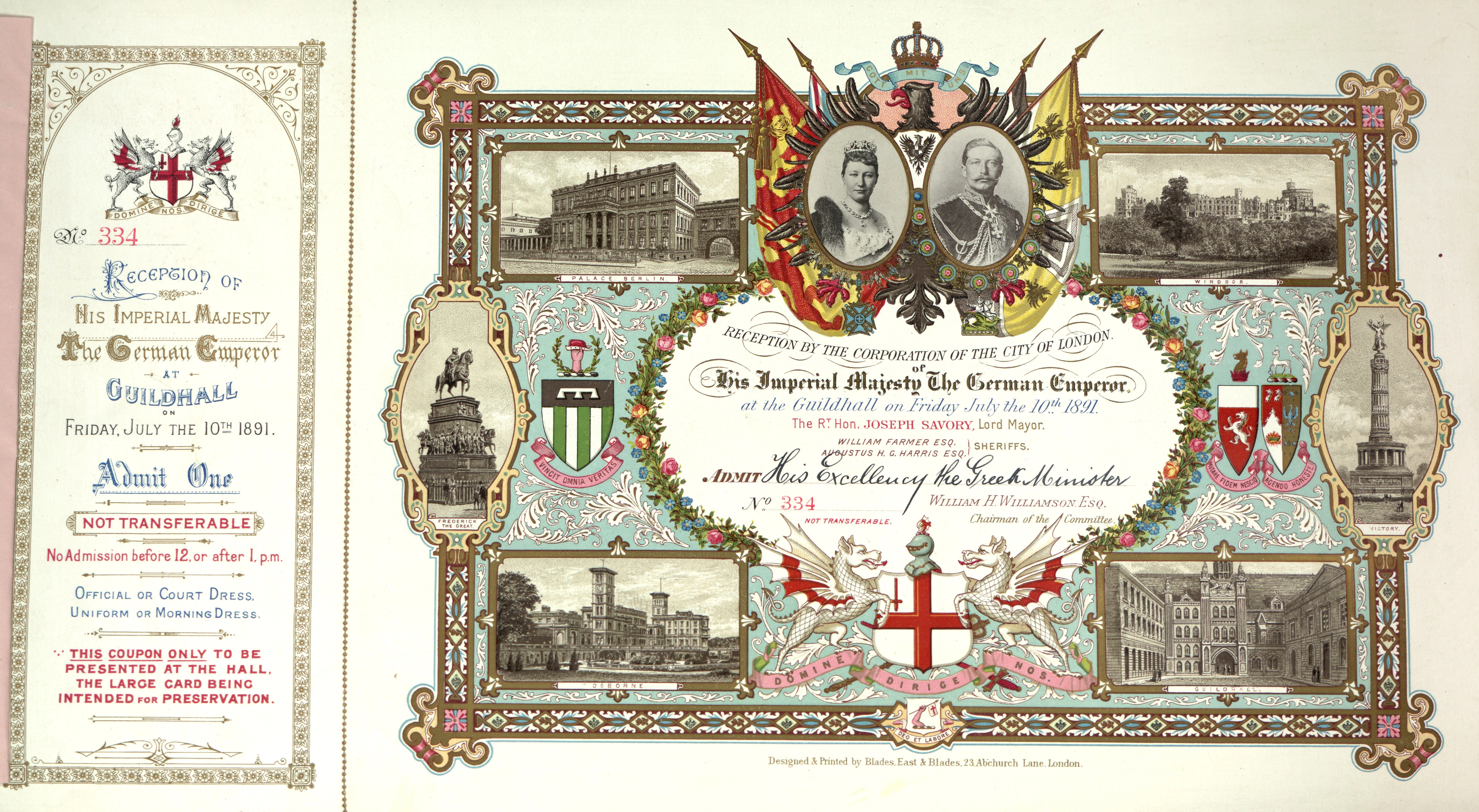

In 1862, he moved to London, where he was employed by the Greek firm of Ralli Brothers. In 1870, he published the pamphlet on the Dilessi murders, which became the starting point for his diplomatic career from 1873 onward. He served in Washington, Constantinople, Vienna, The Hague, and London, where, in 1886, he was promoted to the rank of Minister Plenipotentiary. Forced to resign in 1892, he remained outside the diplomatic service until 1910, when he was reappointed as Greek ambassador to London, a post he held until his retirement in 1918. Gennadius’s pivotal diplomatic positions during the critical period of the Eastern Question and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire make him a unique source on the events of the time, while his extensive travels imbued him with a sense of cosmopolitanism. This exhibition draws on his scrapbooks for relevant information and rare material concerning the War of 1897, the Balkan Wars, the revival of the Olympic Games, the Greek Independence Loans, nd other key moments in modern Greek history, such as the Greek Revolution. His journeys further underscore this cosmopolitan dimension, while the section on Costume books highlights another distinctive aspect of this collection.

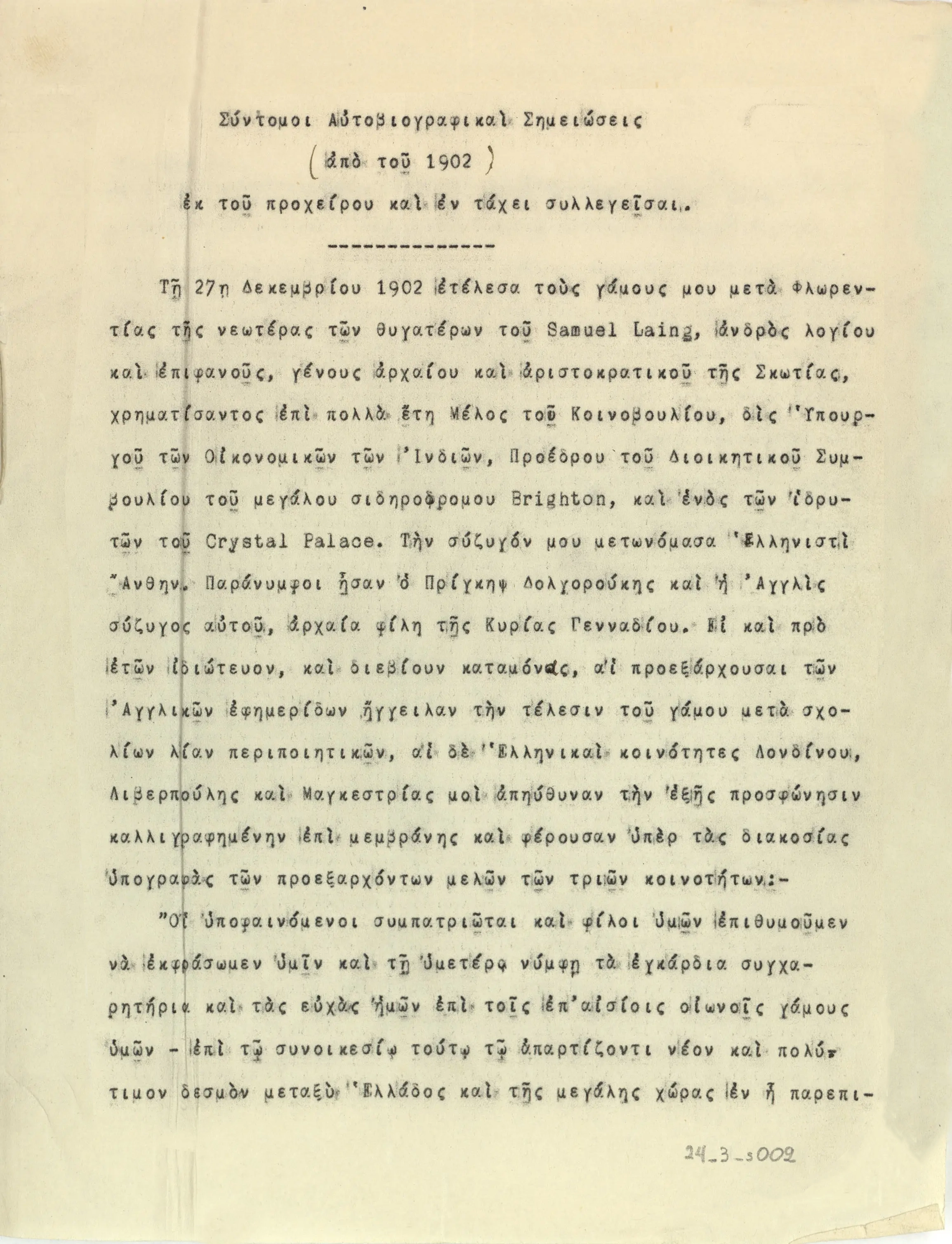

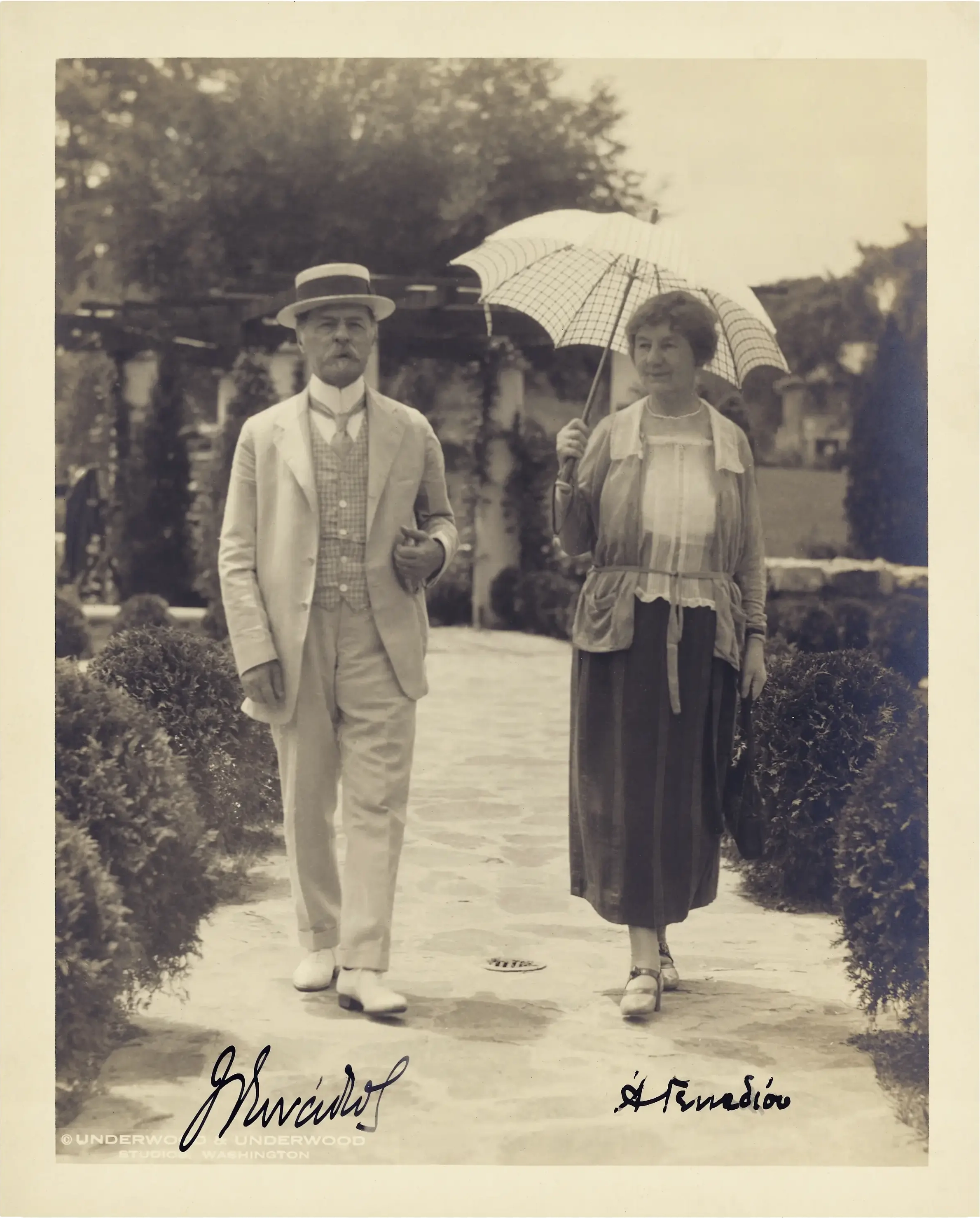

From 1895 onward, Joannes Gennadius devoted himself to writing studies that promoted the Greek cause in Britain, with his most significant achievement being his contribution to the establishment of the Koraes Professorship of Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies at King’s College, London (1915–1918). In 1902, he married Florence Elizabeth Laing Kennedy, whom he renamed Anthi translating her name into Greek.

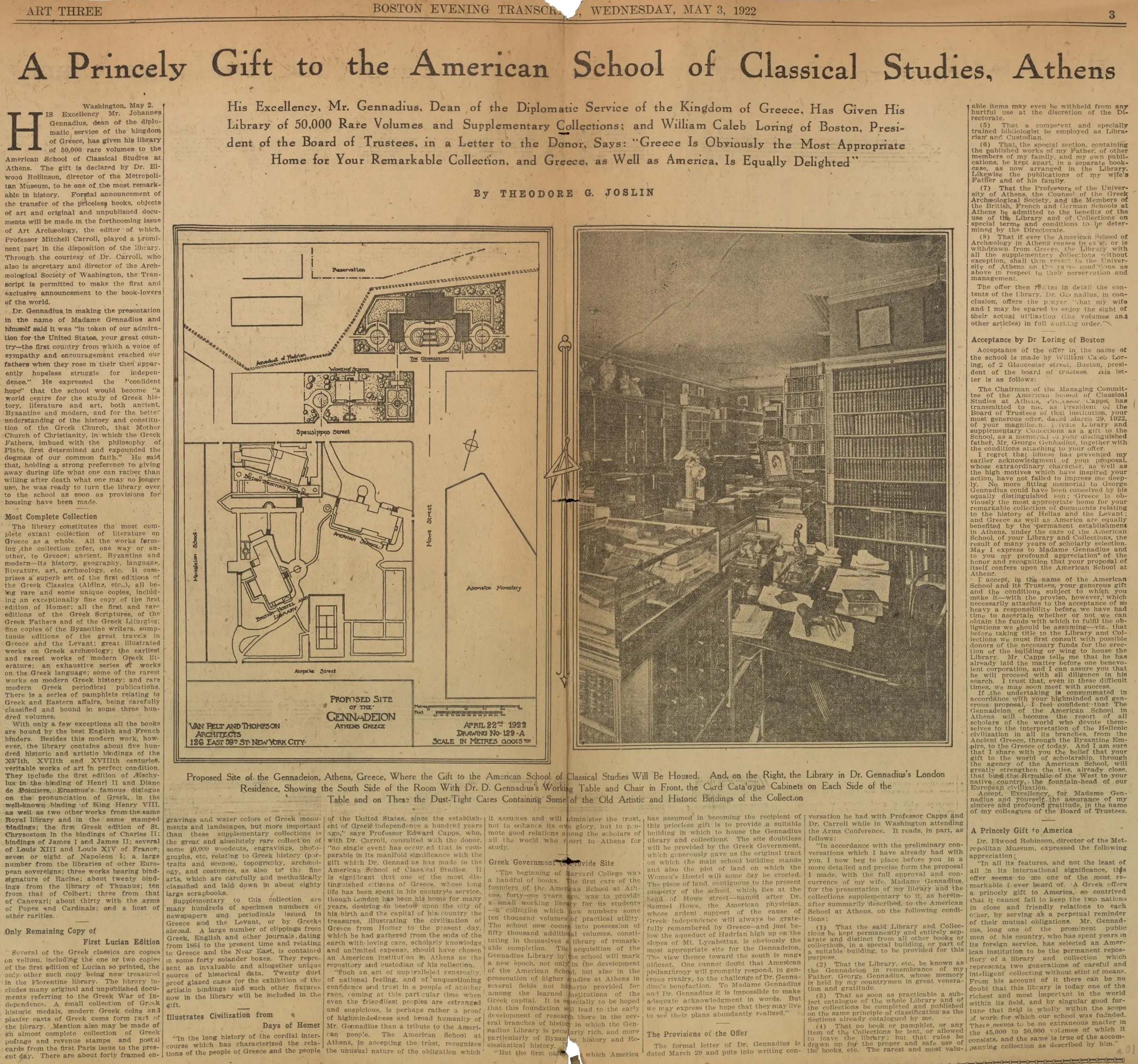

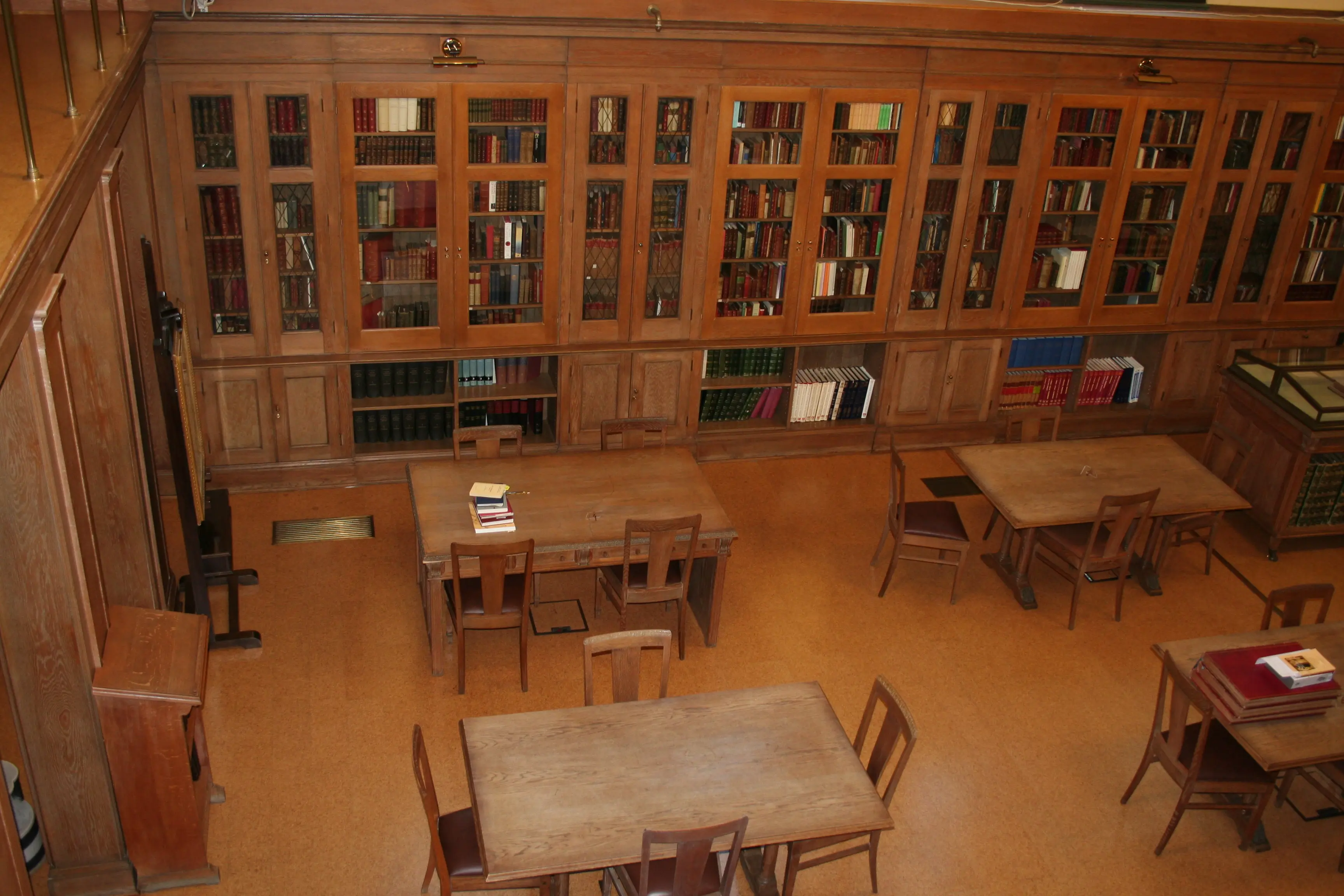

In 1921, he represented Greece at the naval disarmament conference in Washington D.C., and in 1922 he donated his library to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. The opening ceremony of the Gennadius Library took place in 1926, and a few years later, in 1932, he passed away at the age of 88.

The genius of Joannes Gennadius, which inspired him to defend the rights of Greece by undertaking difficult diplomatic initiatives, also guided him—through an unfailing instinct—toward realizing a great vision for his library: the collection of valuable material, in line with his noble aim to create a library that would reflect, in his own words, “…the creative spirit of Greece throughout all periods of its history, the influence of its sciences and arts upon the Western world, and the impression made by its natural beauty and archaeological treasures upon visitors, so that the rarest and most beautiful books might one day return to Greece as an honorary offering to it.”

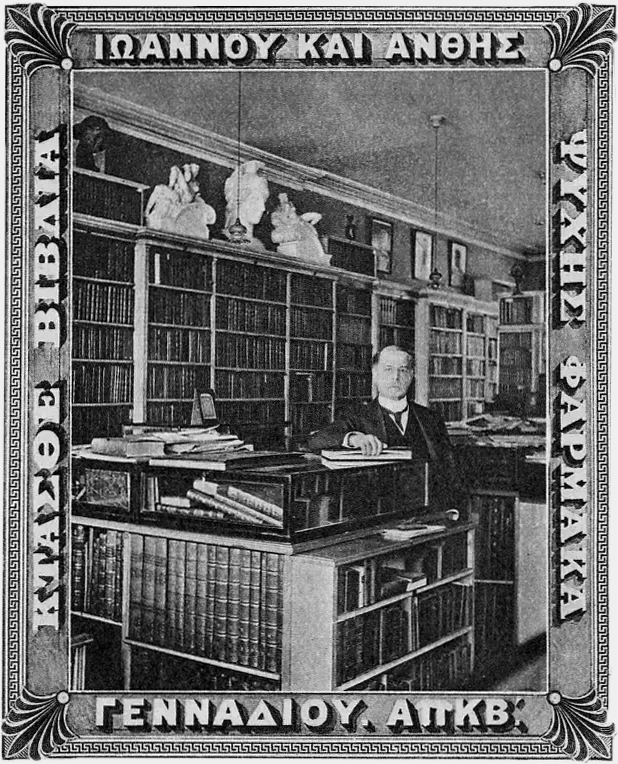

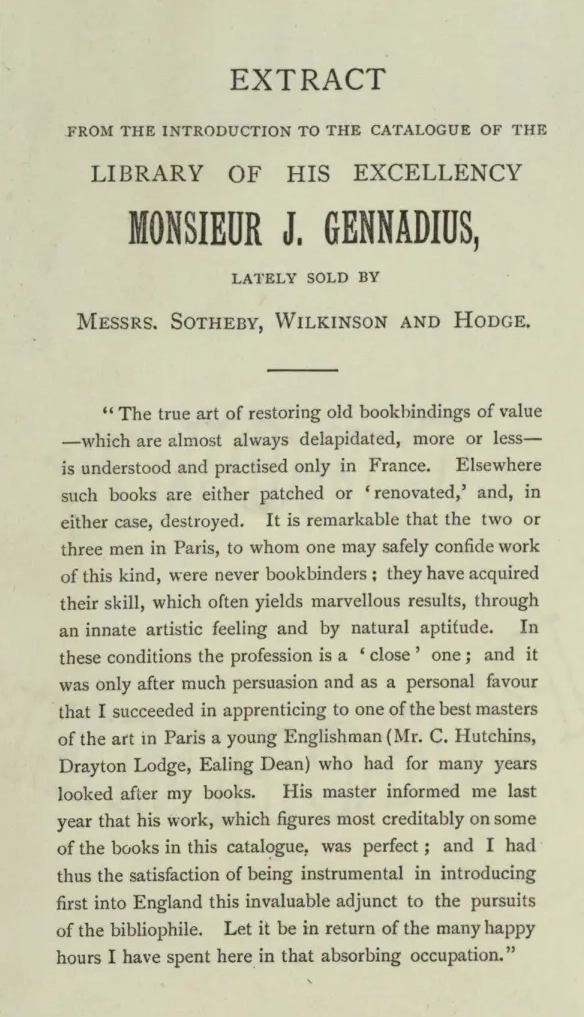

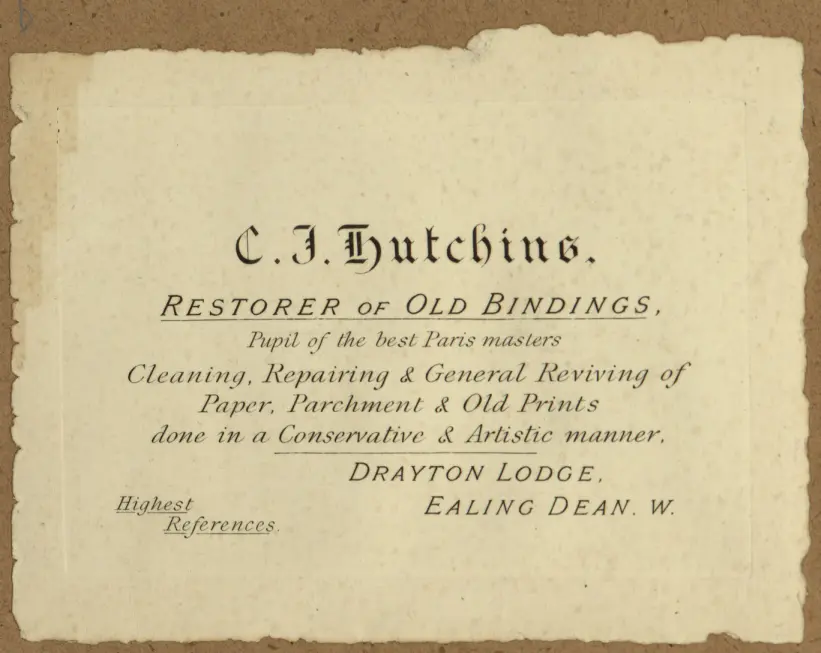

Joannes began his collection after 1870, and by 1895 he had already managed to collect his most important and rare books.

Gennadius inherited his passion for books and for learning from his father, George Gennadius—an ardent supporter of the Greek Revolution, a scholar and teacher, and founder of the University of Athens, the National Library, and other significant cultural institutions of the newly established Greek state.

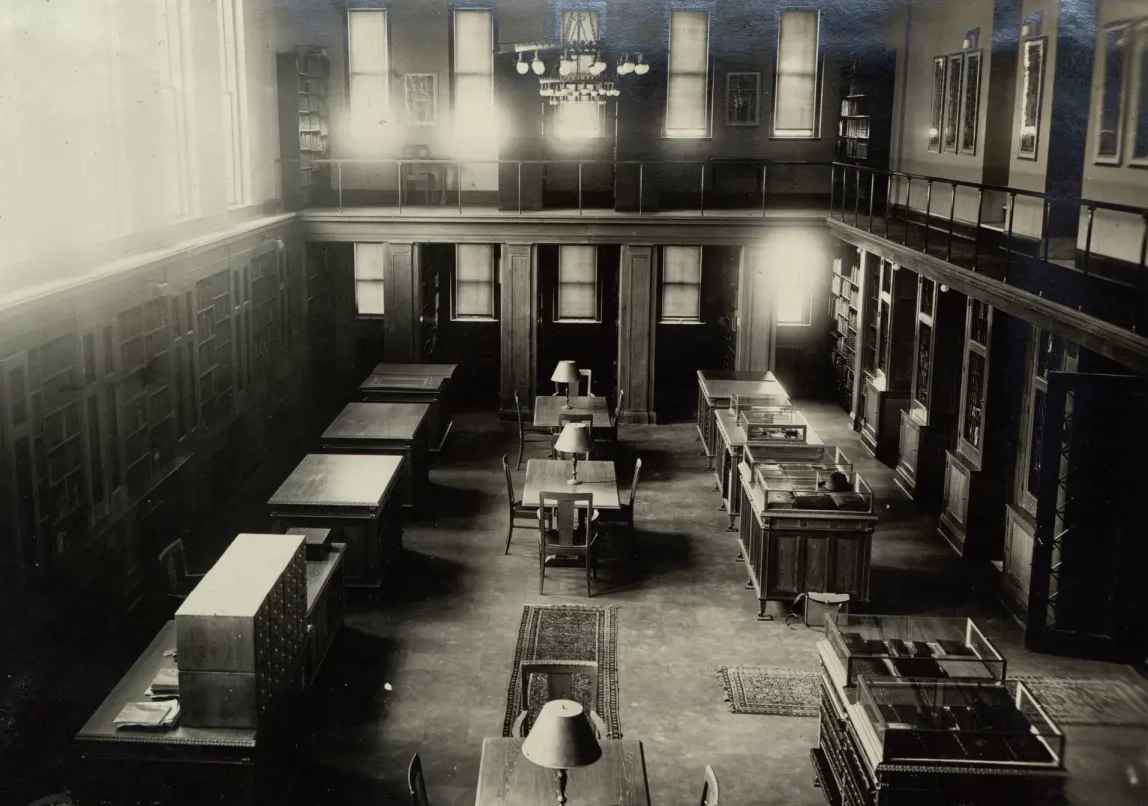

In 1922, Gennadius donated his collection (of approximately 26,000 volumes) to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, on the condition that the School would provide adequate premises for the collection and its staff and would maintain the Library under the name “Gennadeion” in honor of his father.

As expressed in the Deed of Gift of October 18, 1922, Gennadius’s wish was that his library should contribute to making the American School a world-center for the study of Byzantine and modern Greek history, literature, and art. In the same year, Edward Capps, Chairman of the American School’s Managing Committee overseeing its academic work, wrote that the donation of the Library was “the best thing that has happened to the School since its foundation.”

Dedicated to the study of the history of Hellenism, the Gennadius Library is one of the most important libraries of its kind in the world. It is a treasure trove of books, manuscripts, rare bindings, research material, archives, and works of art, serving readers from Greece, the United States, and around the world. Above its imposing bronze entrance doors, the inscription from Isocrates’ Panegyricus — “Greeks are called those who participate in our education”— reminds all visitors of the value of Greek education.

At the heart of the library were (and are) the books, archives, manuscripts, and objects that diplomat and bibliophile Joannes Gennadius spent his lifetime collecting in London.

In the hundred years since its establishment, the Library’s original 30,000 volumes have multiplied to over 150,000 titles. Gennadius, who devoted his life and resources to the collection of rare and distinctive books, focused on Greek civilization from Late Antiquity to his own time. Following the framework and thematic organization set by Gennadius himself, the library covers Greece, the Greeks, and Greek culture from antiquity onward, with particular emphasis on the medieval and modern periods. The collections continue to expand thanks to the efforts of directors, Overseers, and Friends of the Library, as well as through donations and new acquisitions of rare books, manuscripts, archives, and works of art.

True to Joannes Gennadius’s vision, the library has become an invaluable resource for the study of Late Antiquity, Byzantium, the Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, modern Greek studies, and humanism, attracting scholars from around the world. Today, thanks to the generosity of the Trustees of the School and the Library, and to the dedication of its Managing Committee, staff, and Friends worldwide, the library stands close to fulfilling Gennadius’s vision: to become a world-center for the study of Hellenism.

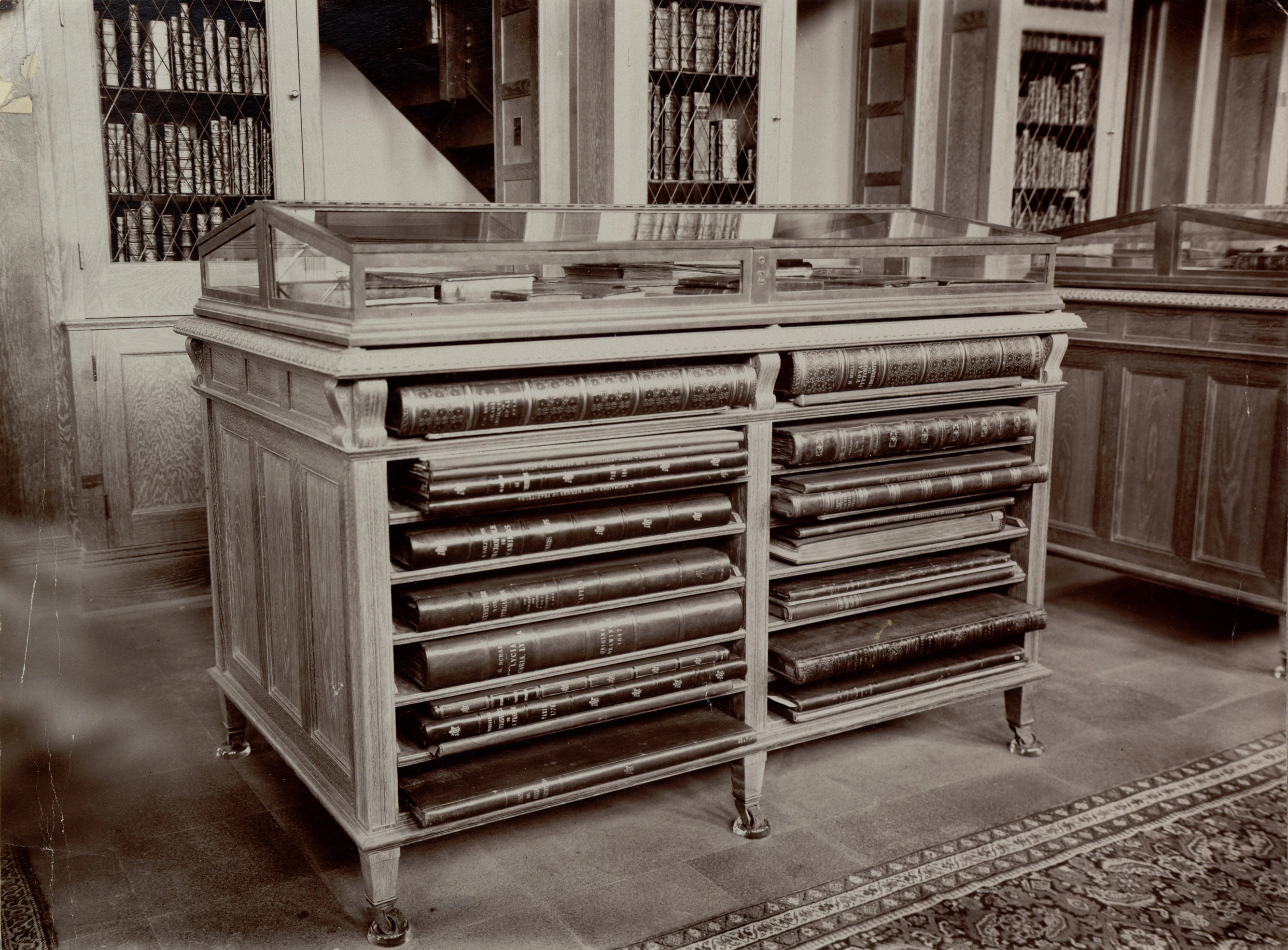

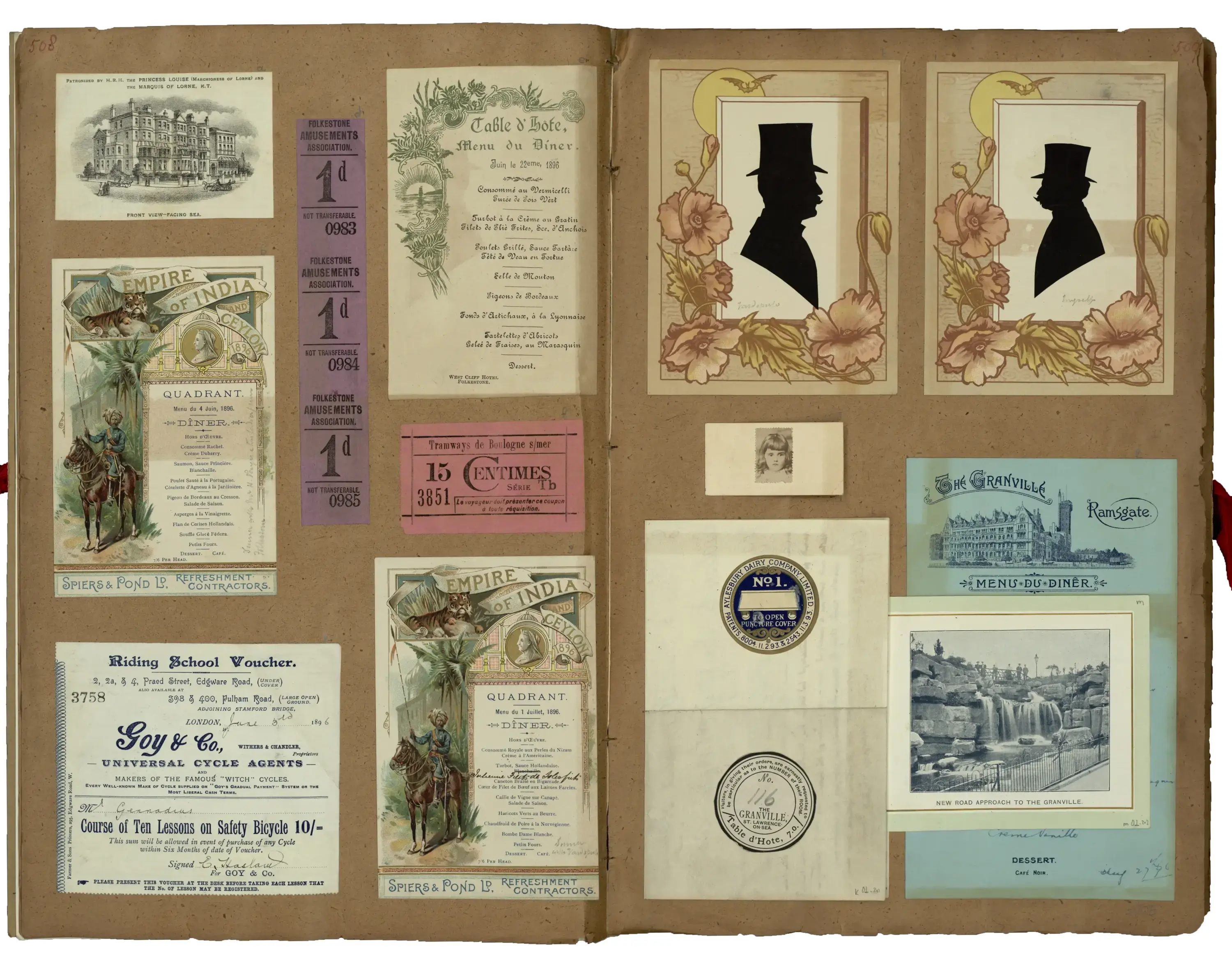

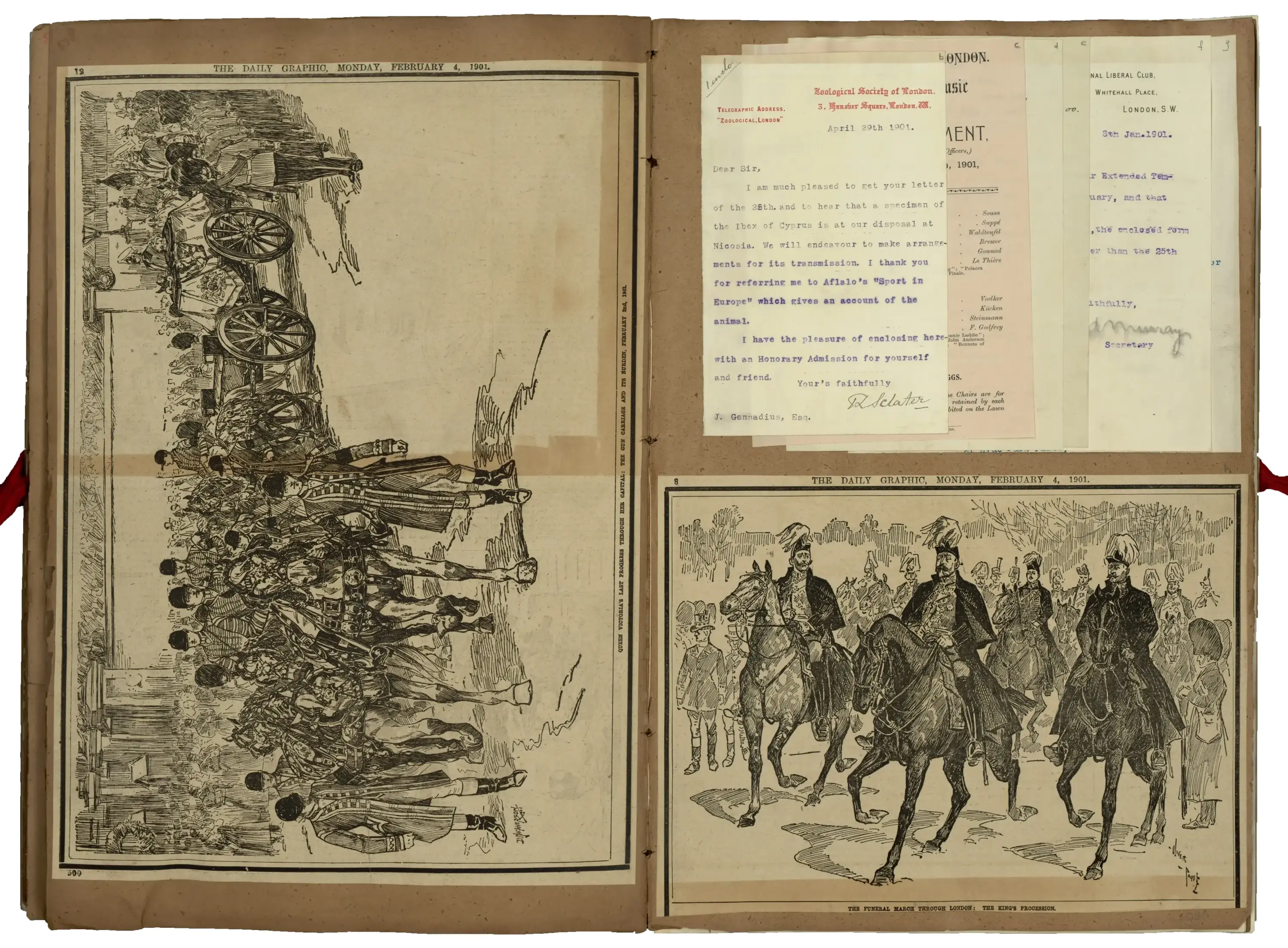

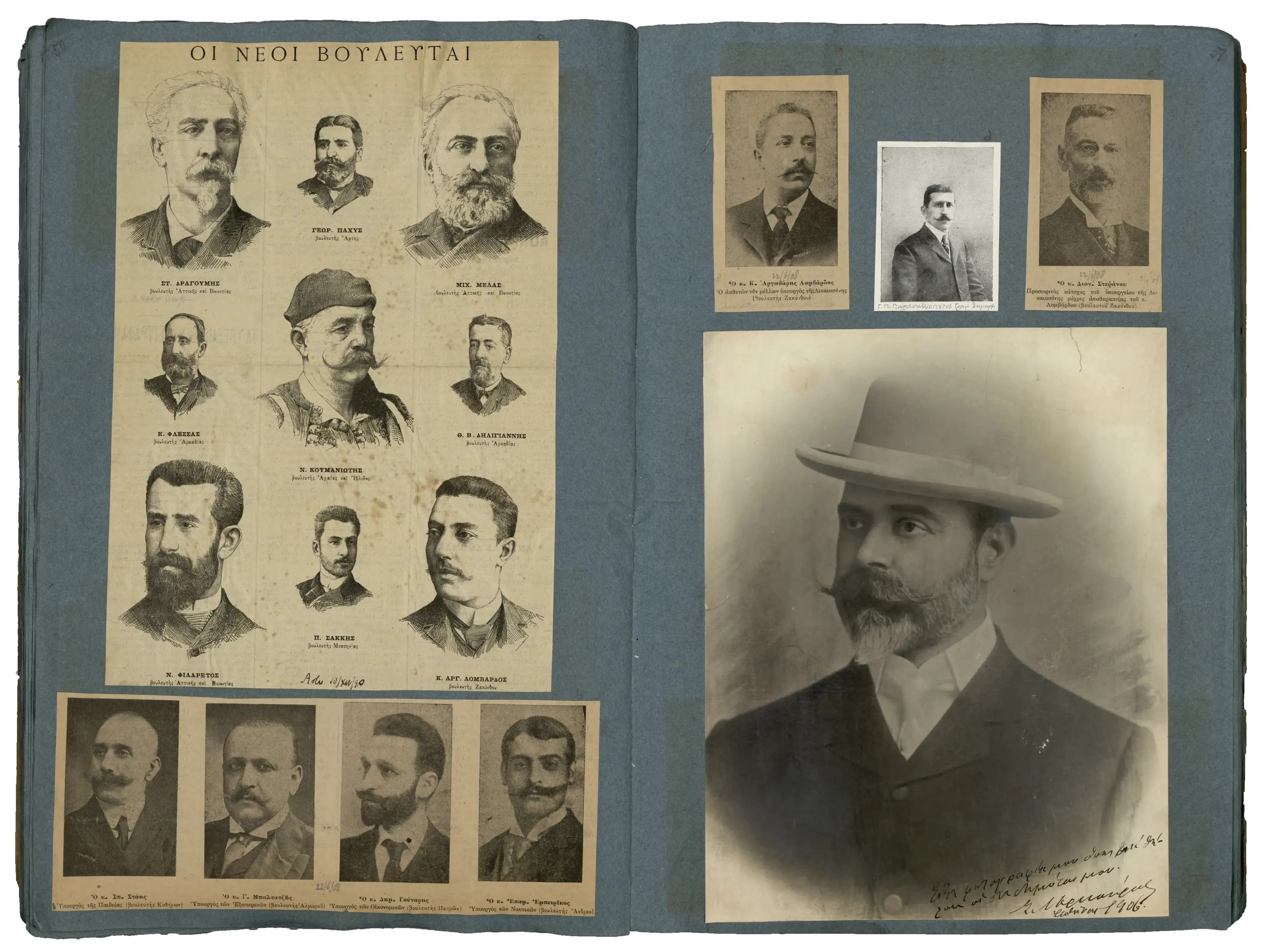

From an early age, Joannes Gennadius collected prints related to Greece and other subjects, carefully pasting them into scrapbooks. These scrapbooks are unique in their wide thematic range, encompassing items on history, topography, archaeology, ethnography (costume albums and prosopography), architecture, art, bibliography, journalism, and even material related to Gennadius’s family.

Beyond prints, Gennadius’s 116 scrapbooks also contain photographs and a wealth of ephemera: newspaper and book clippings, printed matter, broadsides, invitations, and more. Each volume averages 60–70 large-format leaves, designed in a complex manner. Documenting them has been a true feat of scholarship, accomplished through European research projects in 2007 and again in 2024.

Portraiture and topographical materials from these scrapbooks were already widely used in the 1970s to illustrate the multi-volume History of the Greek Nation published by EKDOTIKI ATHINON, intended for a general audience. This exhibition, however, presents lesser-known materials that offer invaluable insights into the history of modern Greece and into the personality and world of Joannes Gennadius.

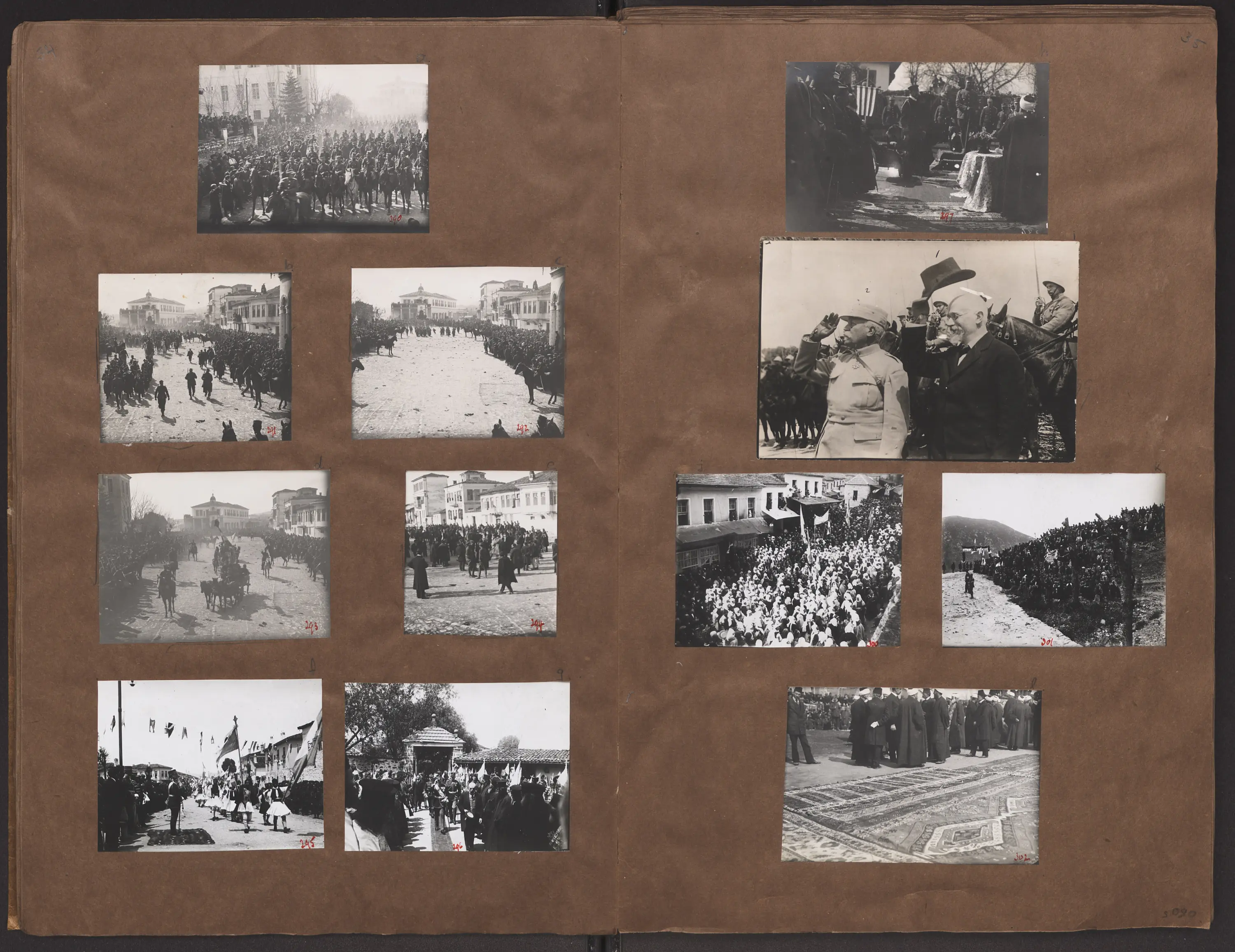

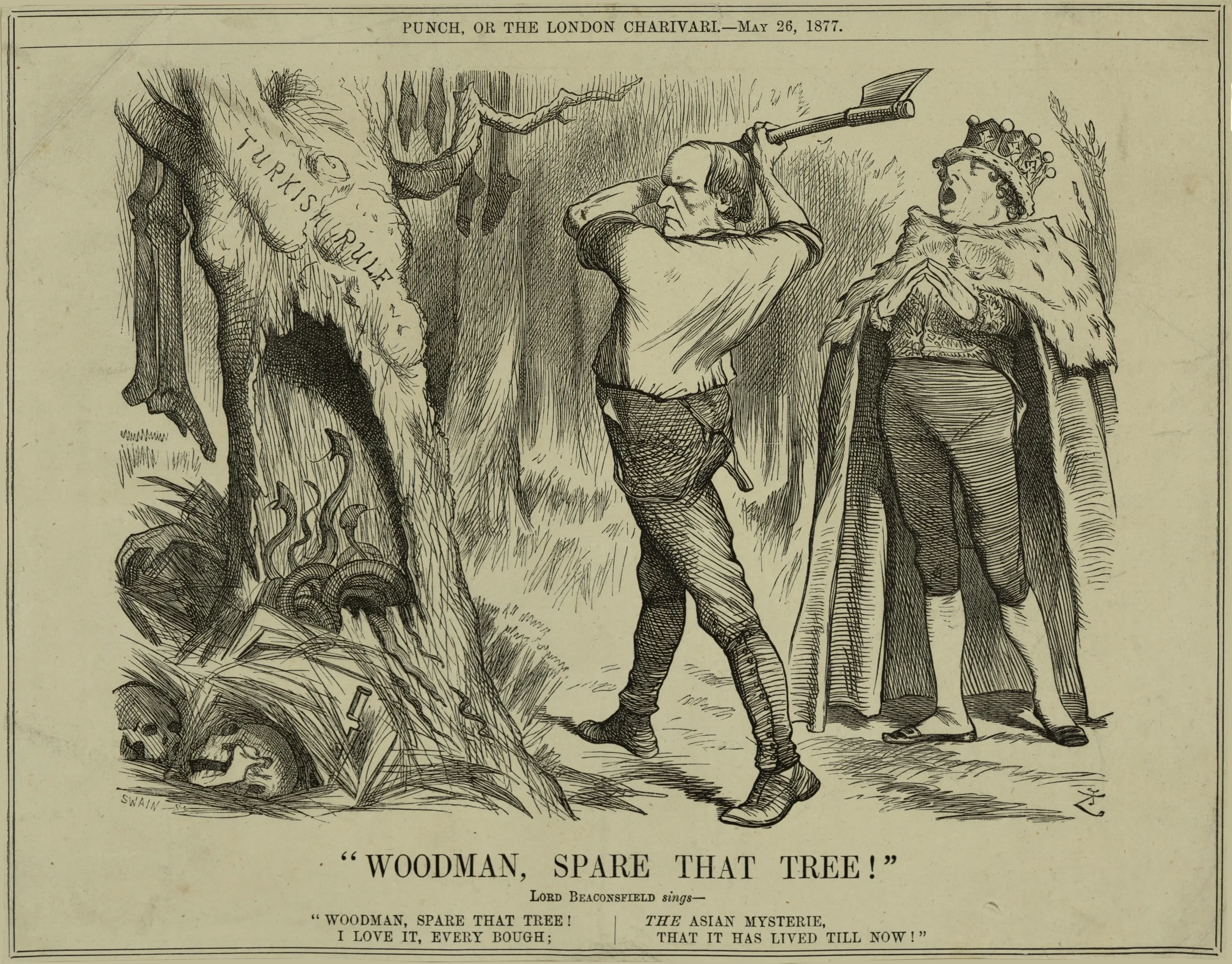

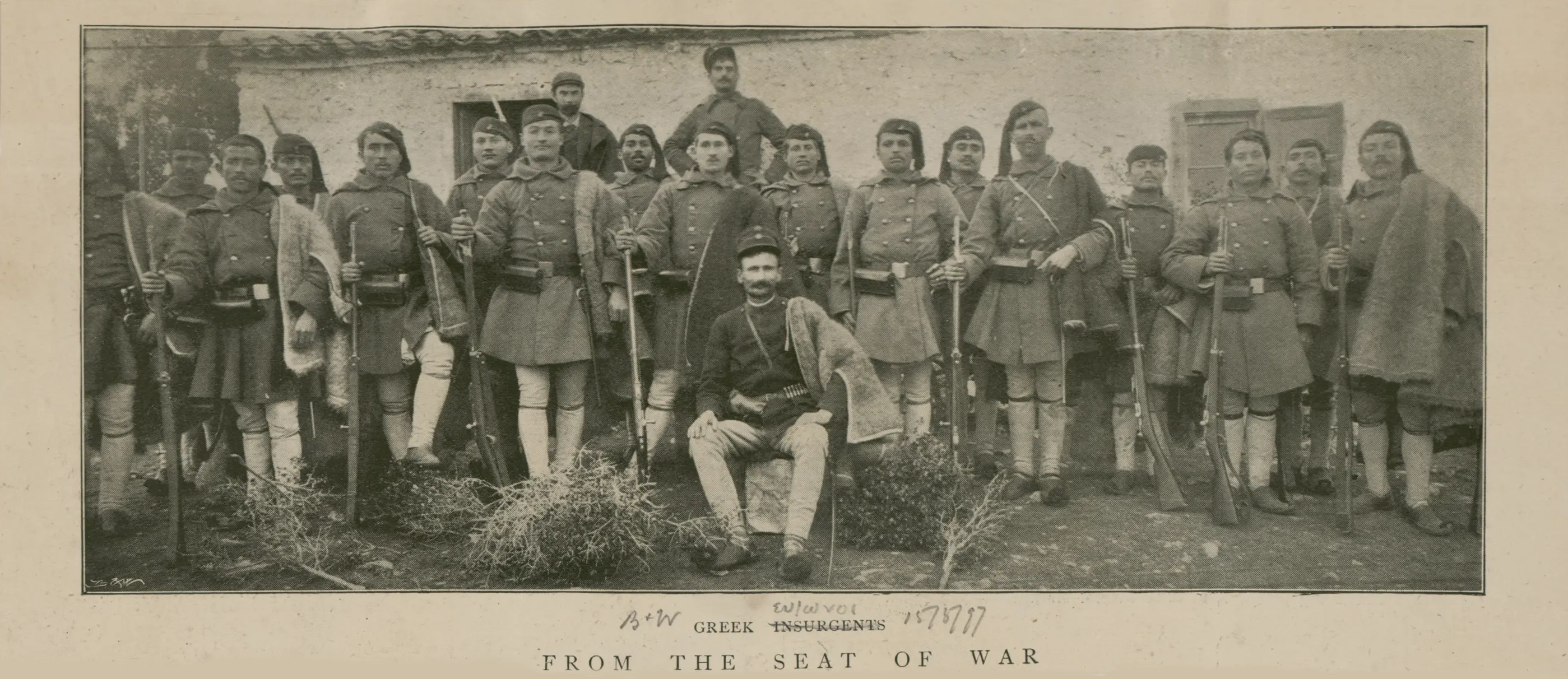

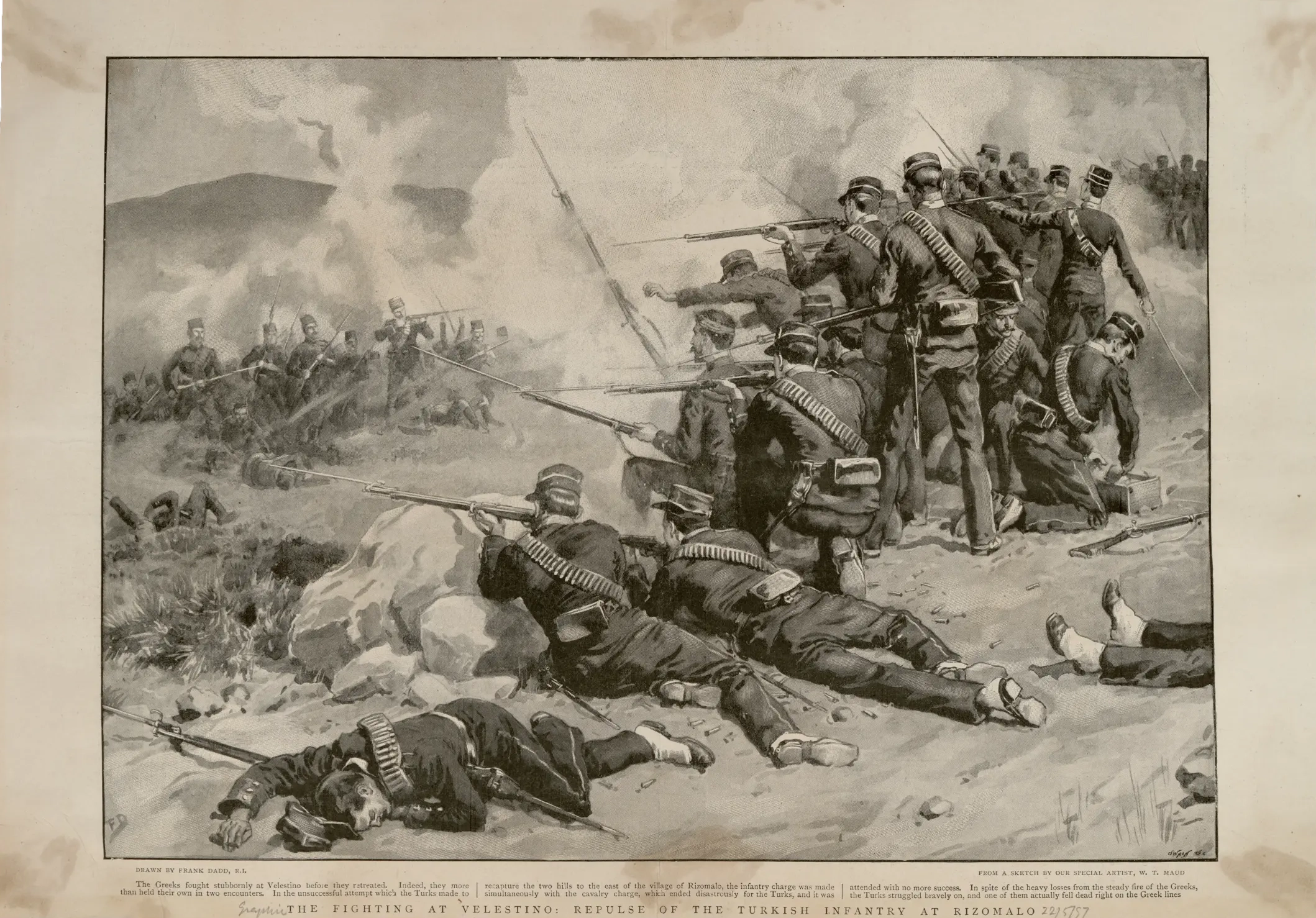

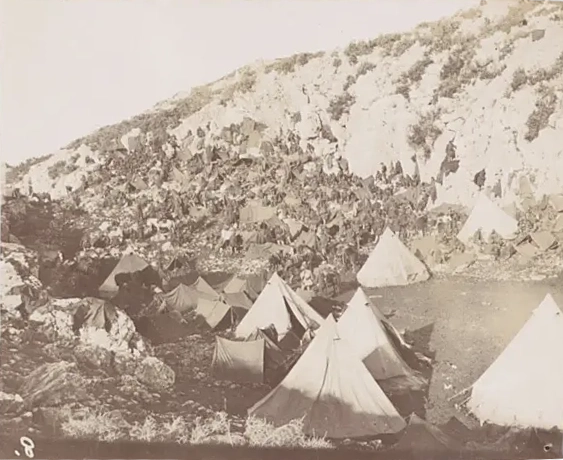

For instance, the volumes devoted to the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 (vol. 36) and the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 (vol. 35) contain unique primary photographic material collected by Gennadius himself. Even a brief glance at the caricatures preserved within opens new horizons for the study of satire and the ways historical events were received in both Greece and the United Kingdom.

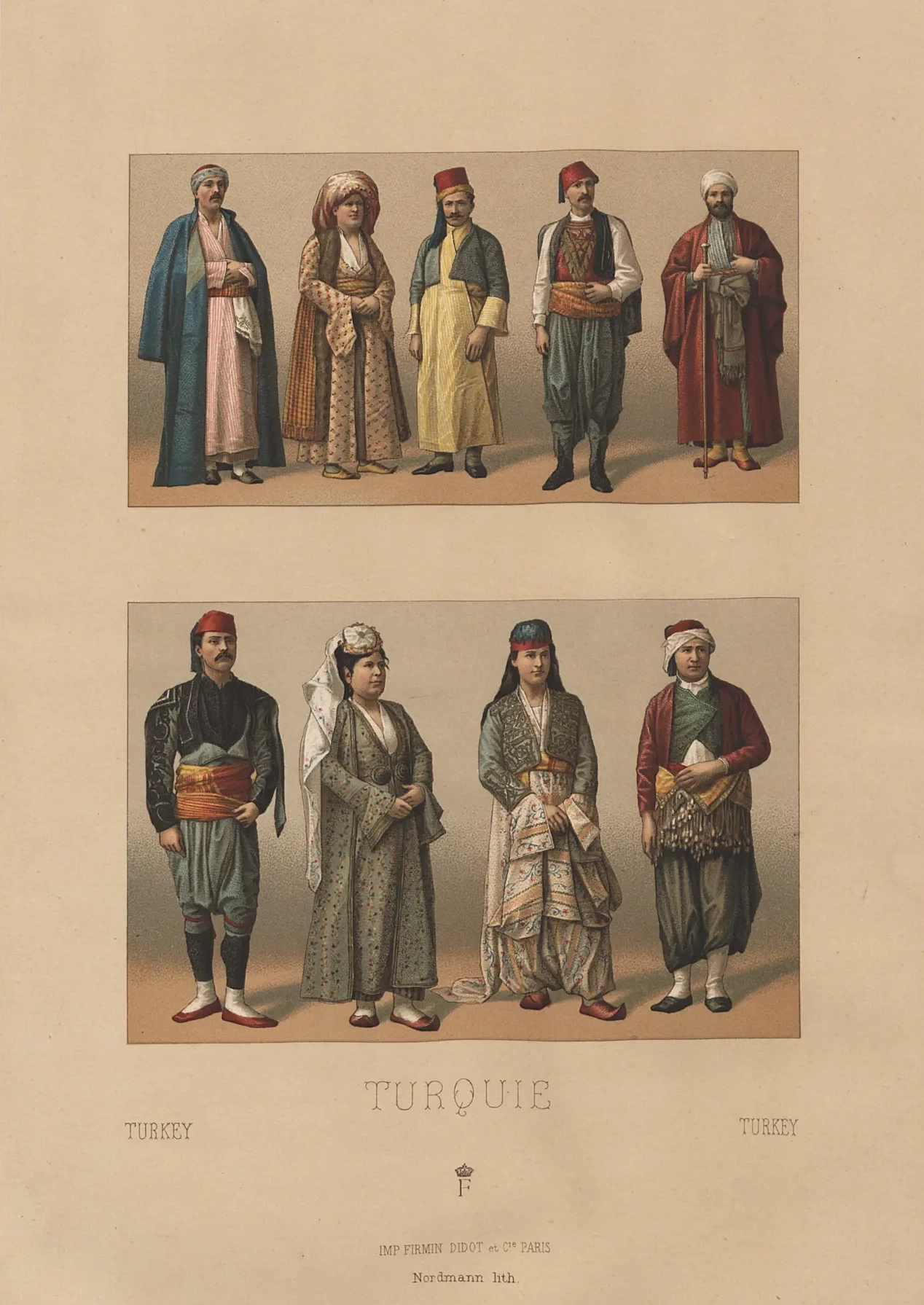

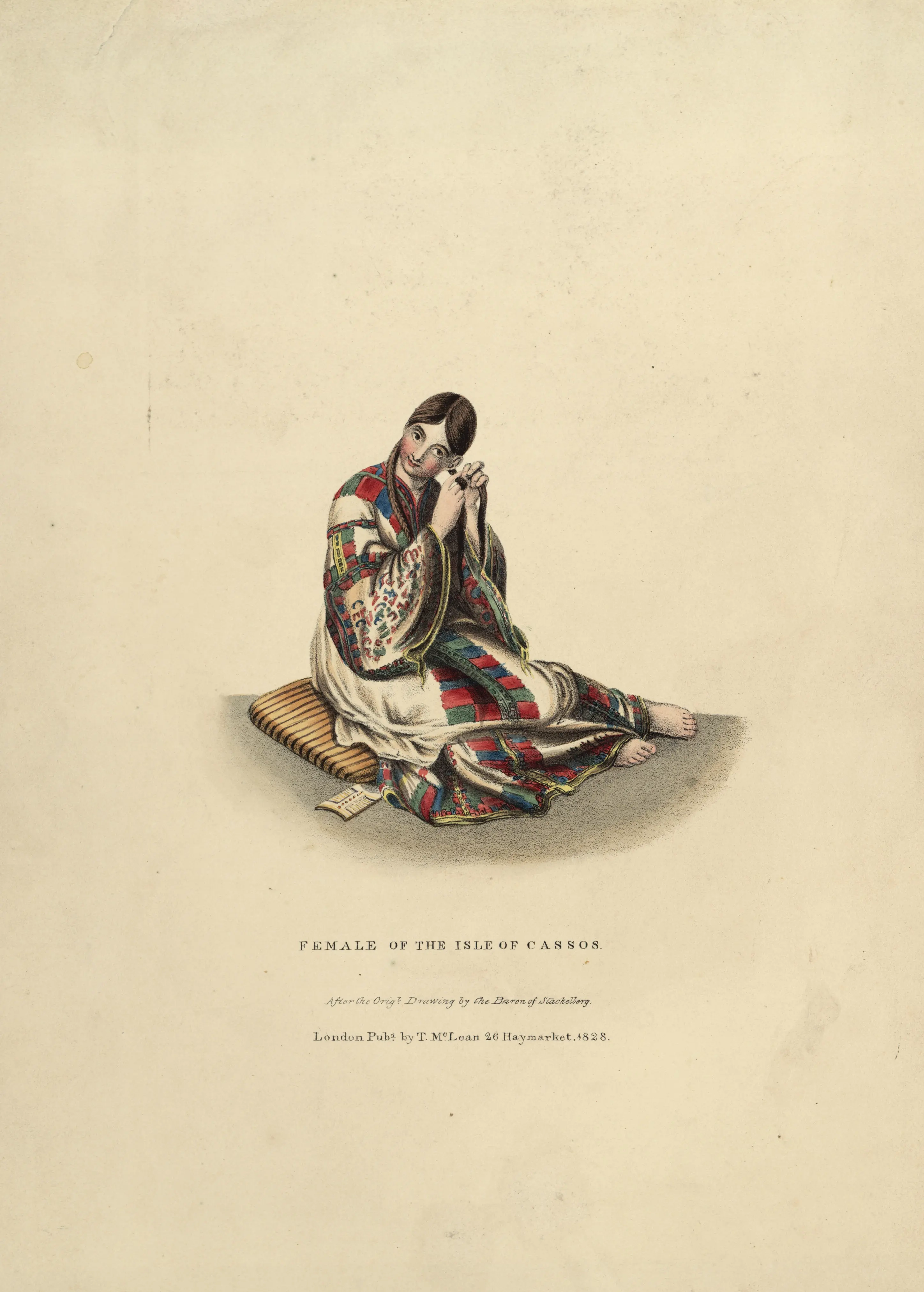

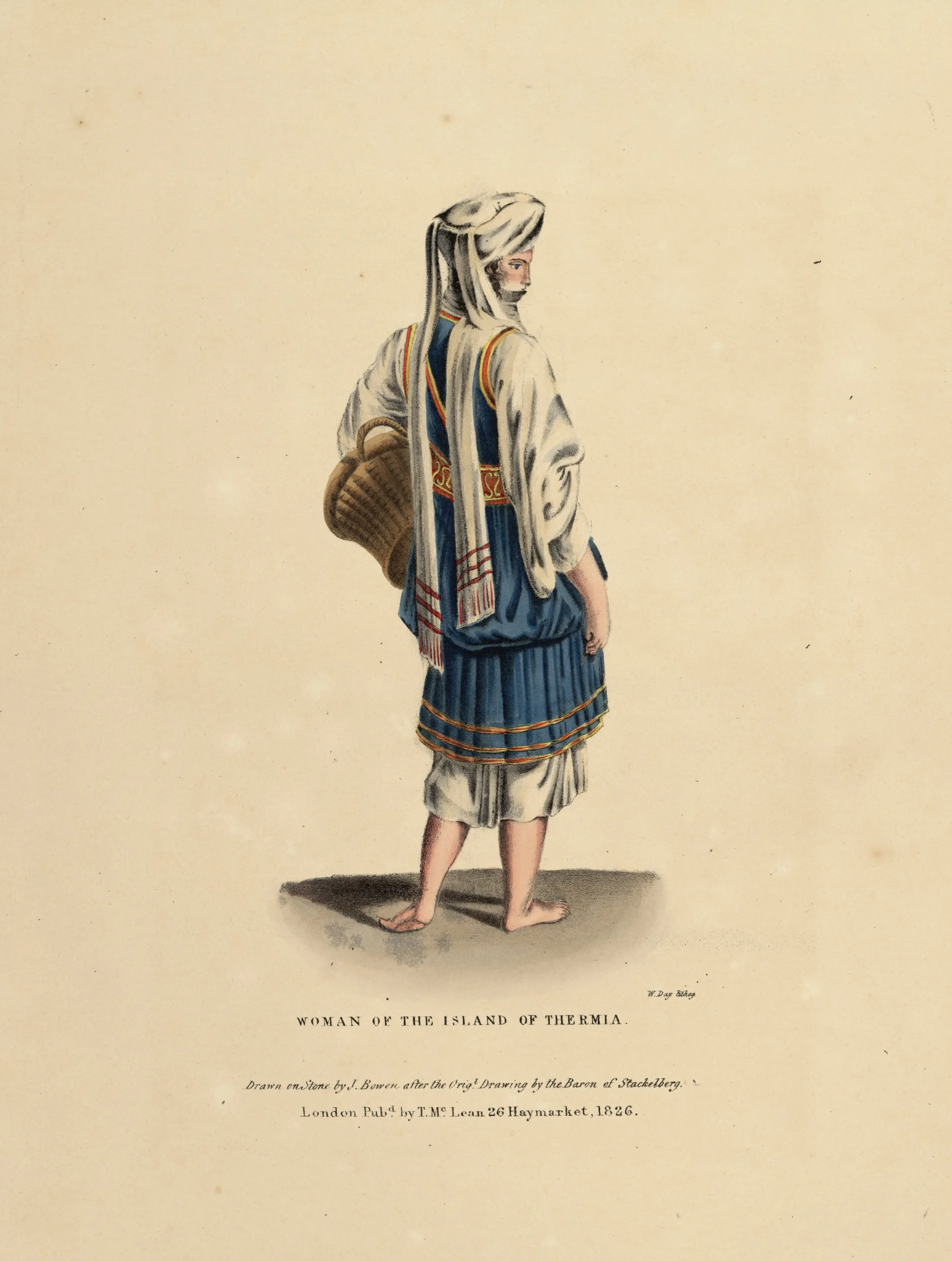

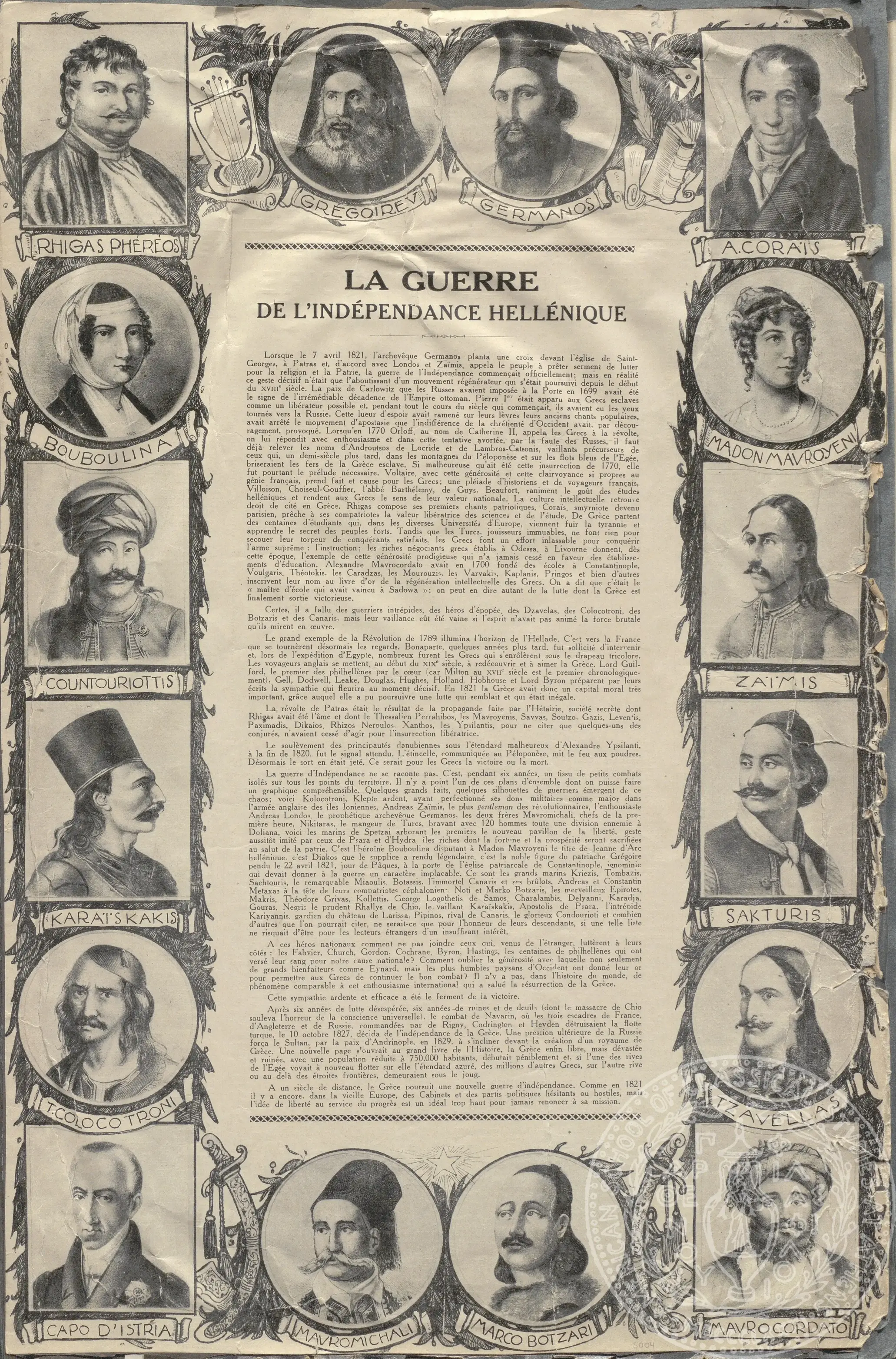

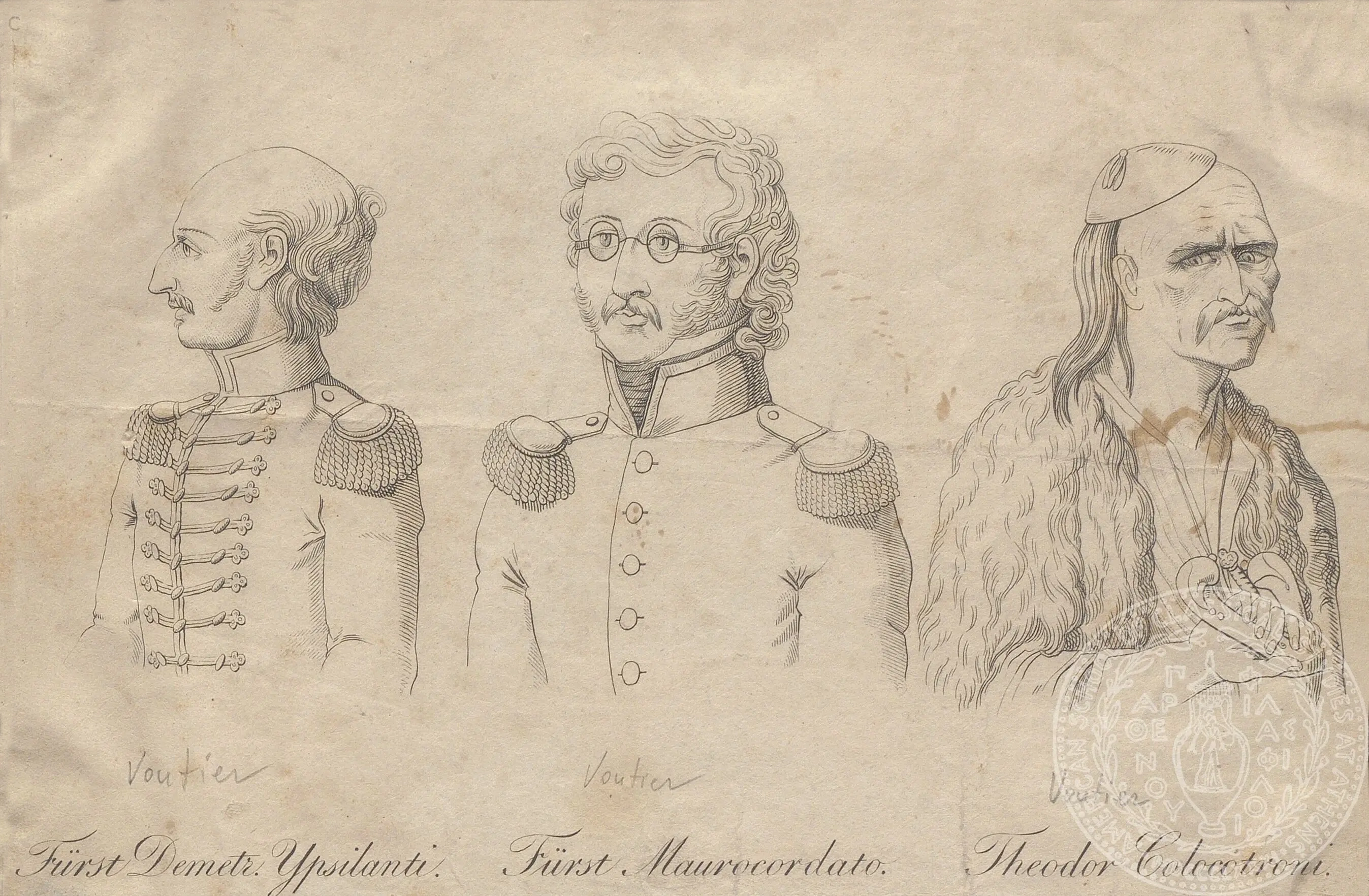

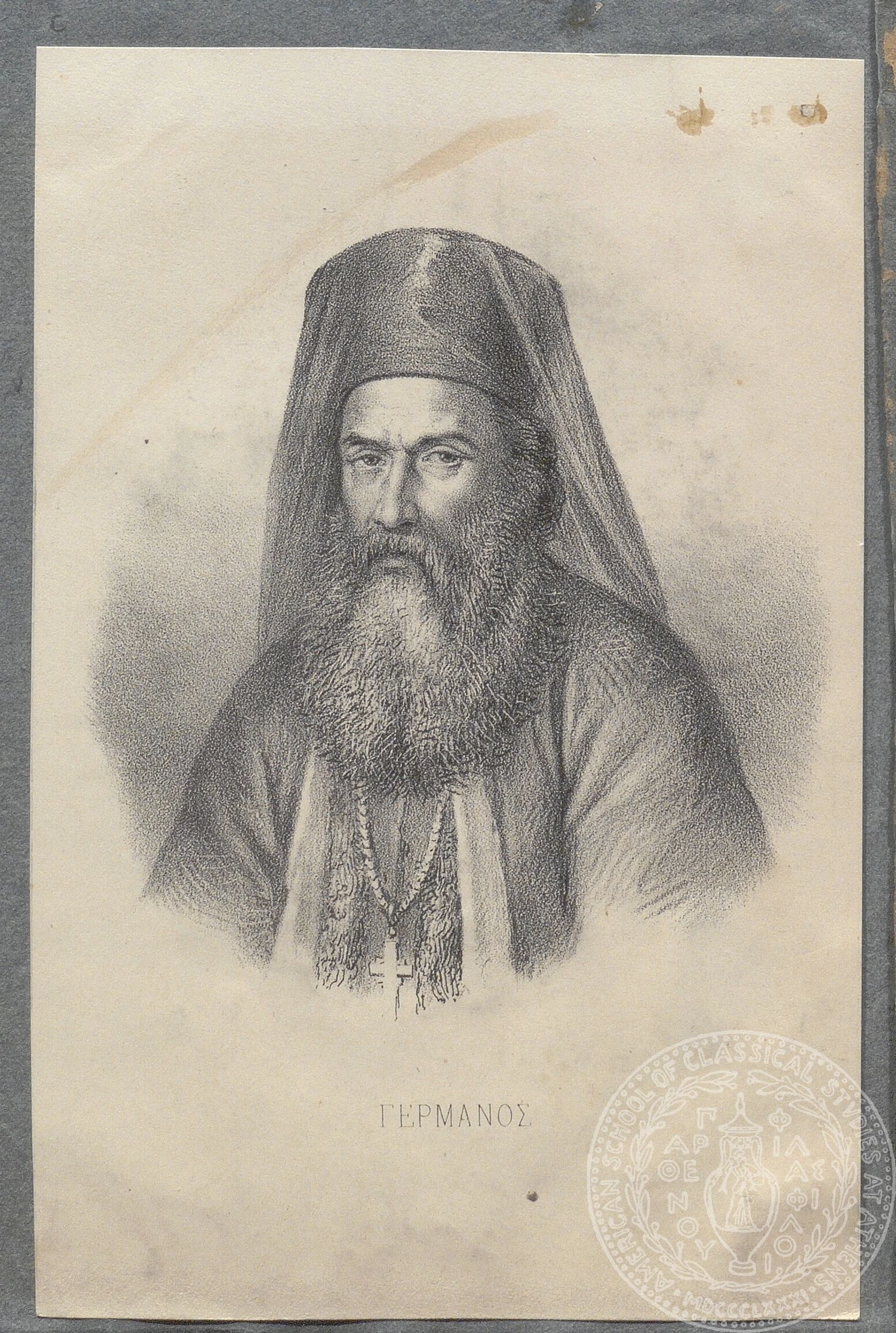

Scrapbooks devoted to prosopography include portraits of prominent historical figures, beginning with heroes of the Greek War of Independence, as well as contemporary personalities, while the scrapbooks devoted to costume (Vols. 58–66) complete the picture Gennadius left us of these themes.

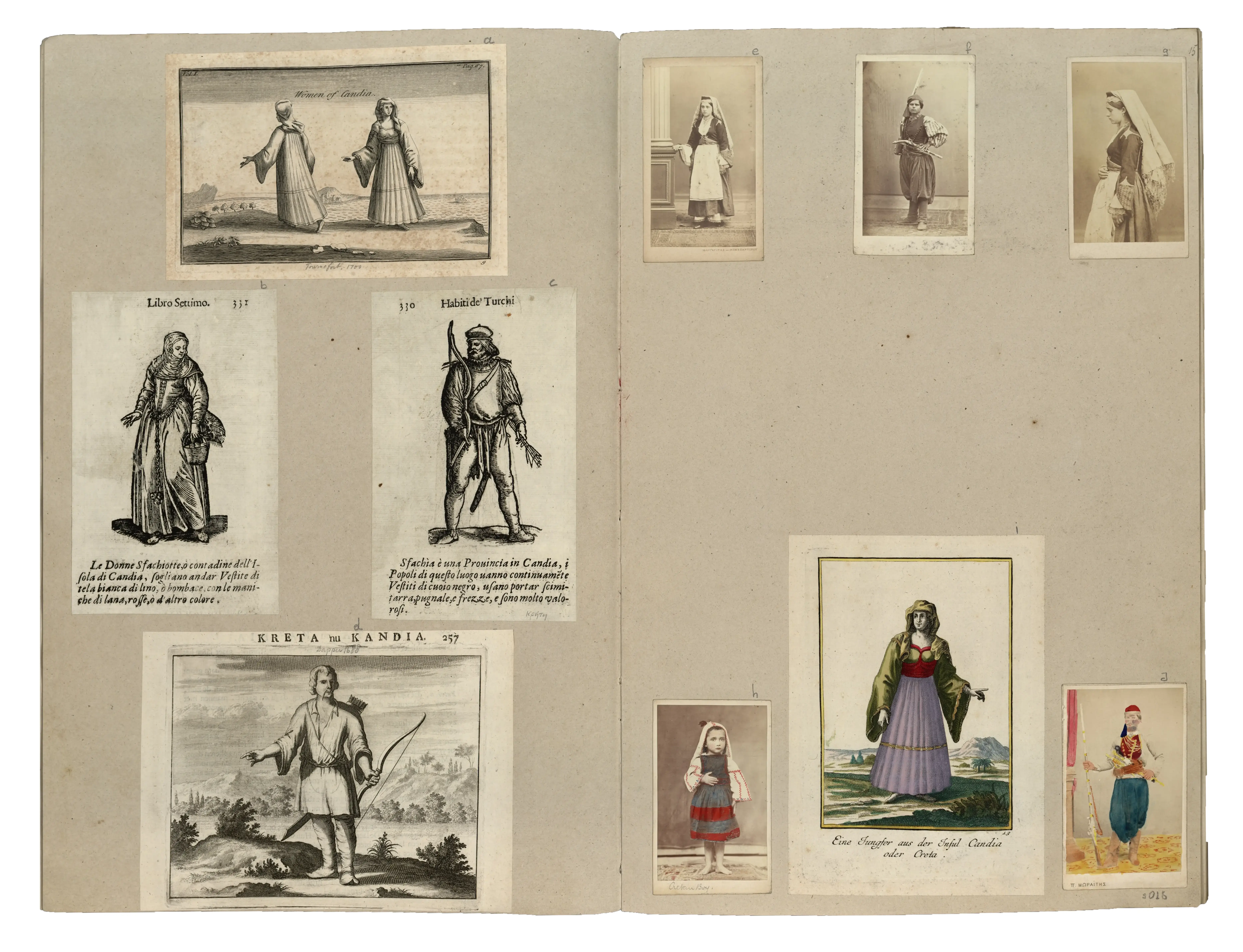

Costume books

The collector’s passion for depictions of costumes from the Ottoman Empire—both in printed books and in drawings or handmade albums—reflects a broader fascination with cultural representation and historical costume.

With the primary aim of satisfying curiosity and alleviating Europeans’ fear of the Ottomans, costume books familiarized the West with exotic Oriental customs from the 16th to the 19th century. The depictions of Ottoman costumes enabled Europeans to gain insight into Ottoman society and the way in which it operated. Such books also served as practical “guides” for diplomats and others intending to visit the Sultan’s court.

The artists were, at first, European travelers to the East, but by the early 18th century Ottoman artists themselves began to imitate the genre, recognizing the high demand for such illustrations. The subject remained popular even after the advent of photography in the mid-19th century producing well known orientalist images.

In these scrapbooks, costume points directly to specific geographic regions or social classes, with the images acting as self-evident truths of an otherwise unfamiliar reality. Costume, as a symbol of cultural difference, represented the way of life, and thus shaped how the West perceived and re-imagined the East. While these publications claimed authenticity, they nonetheless adapted themselves to the commercial expectations of a European readership, reproducing familiar patterns, such as gender roles and social classes.

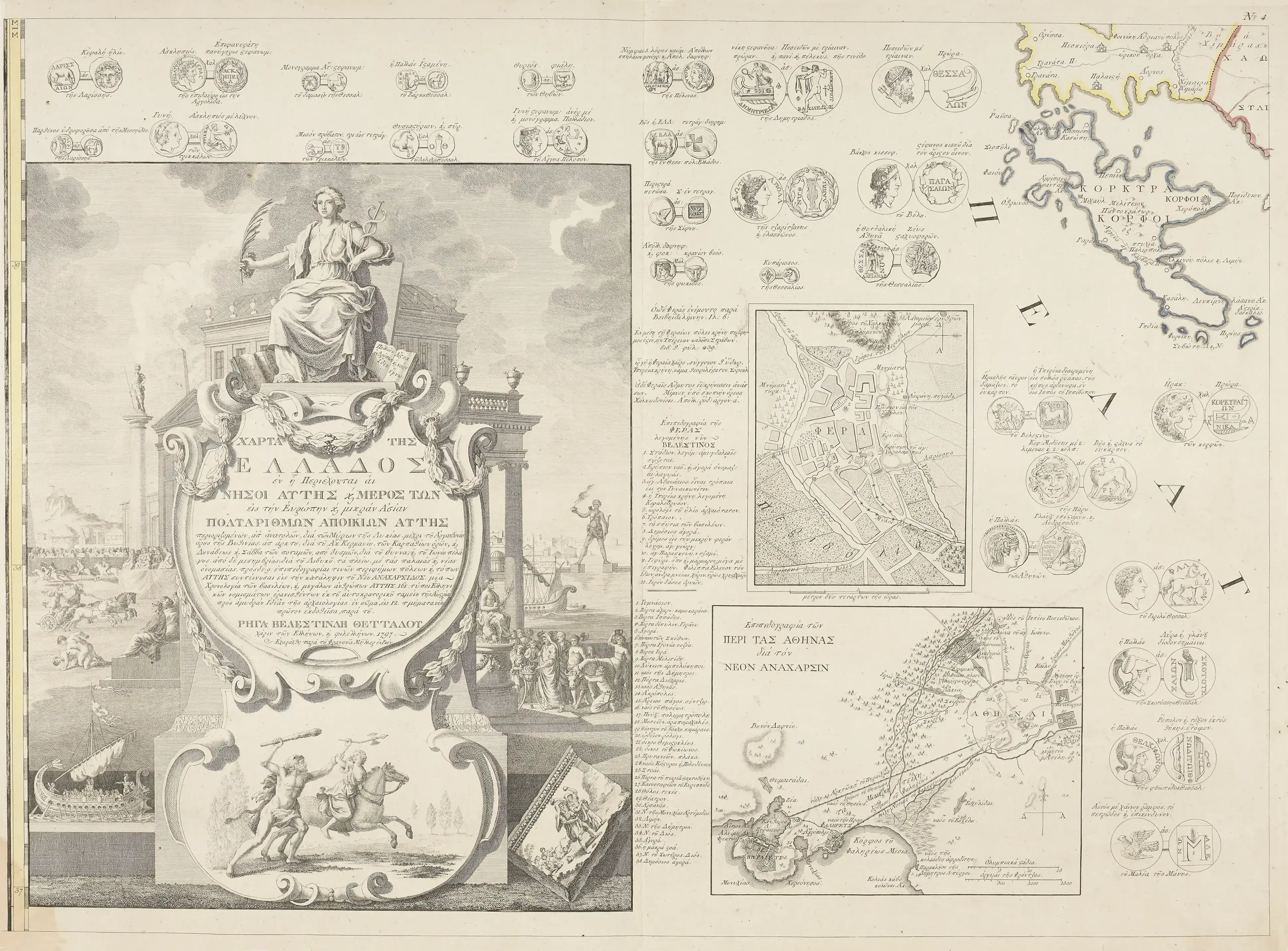

The Greek Revolution of 1821

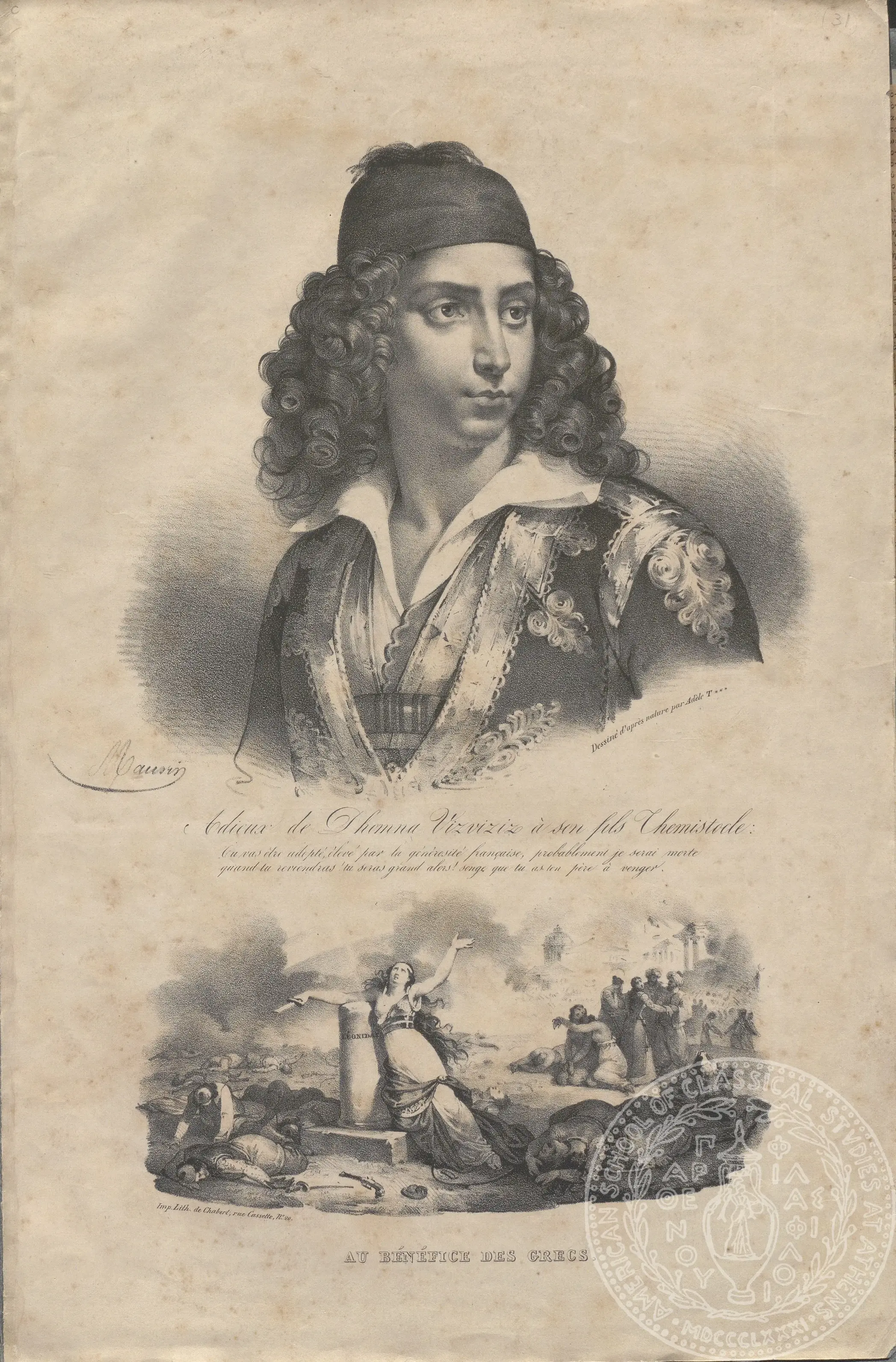

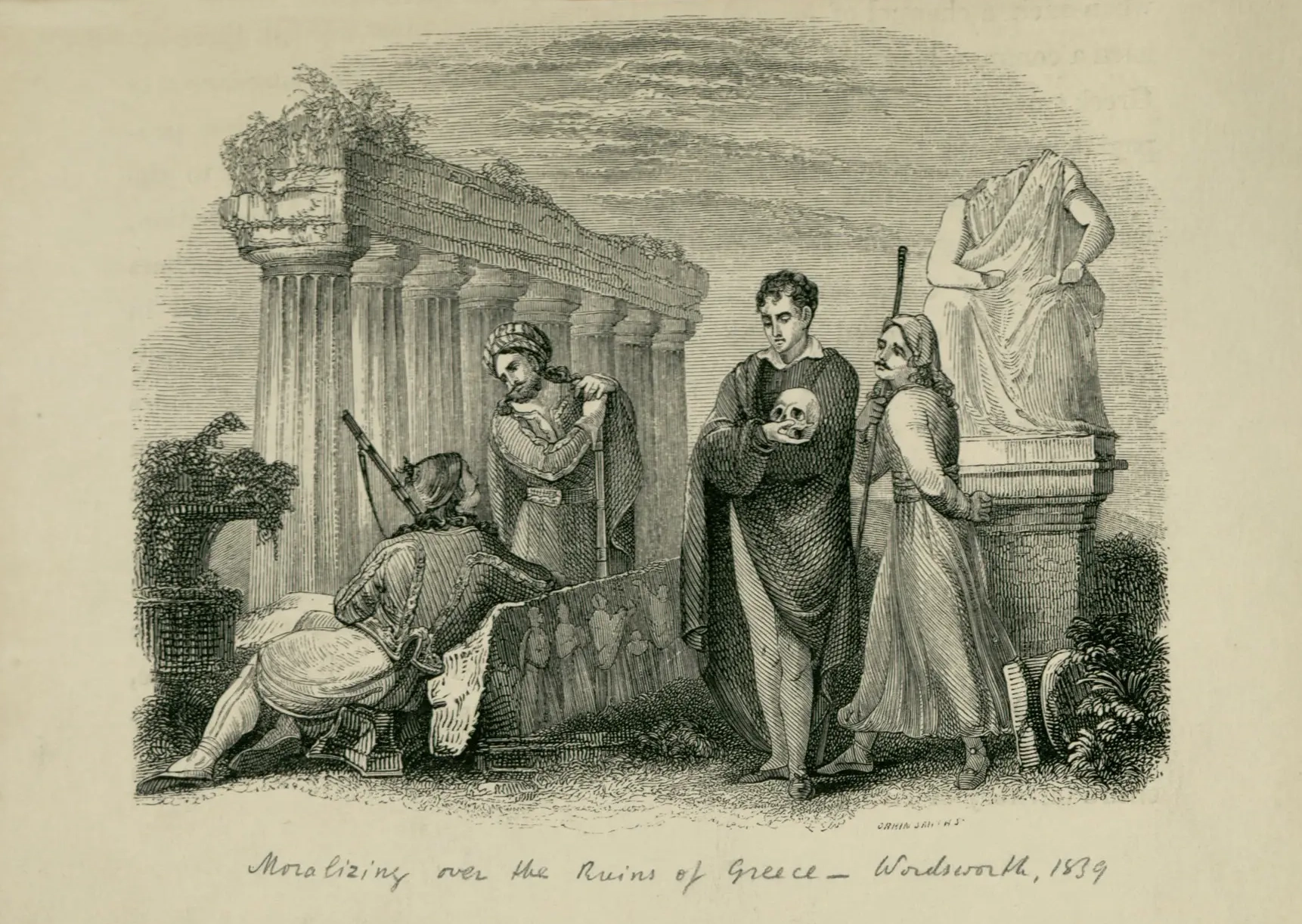

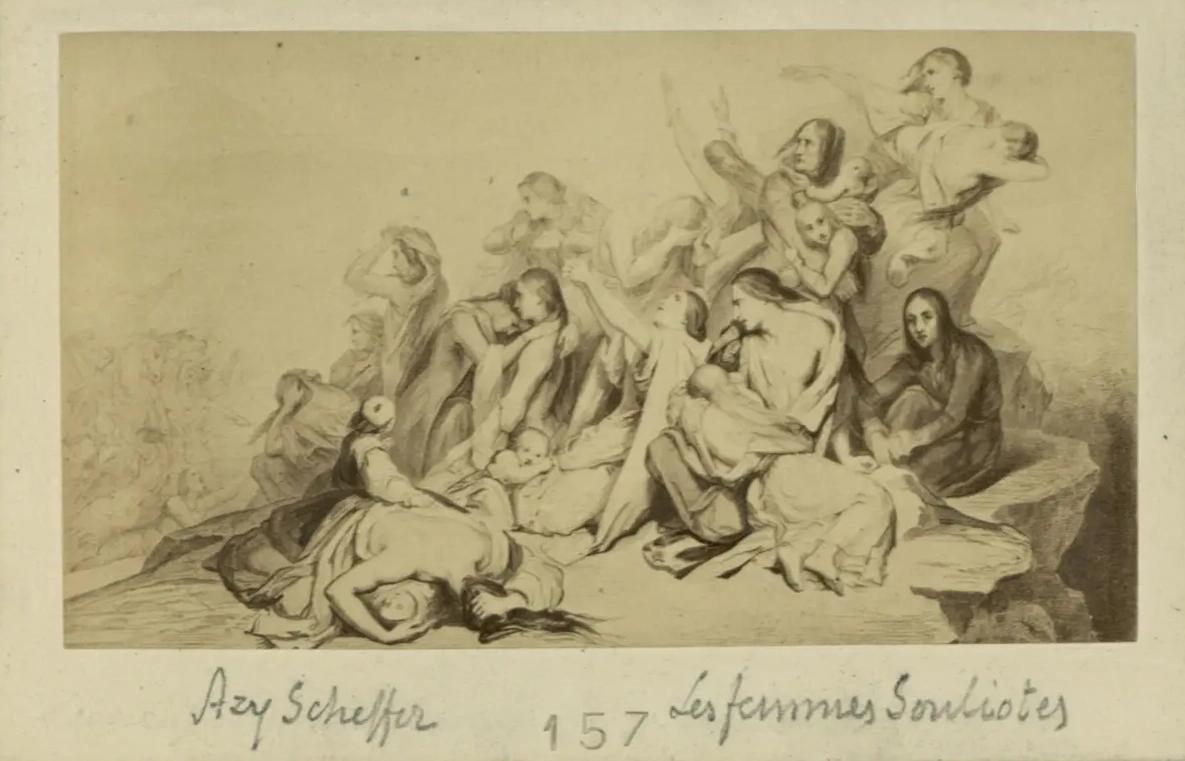

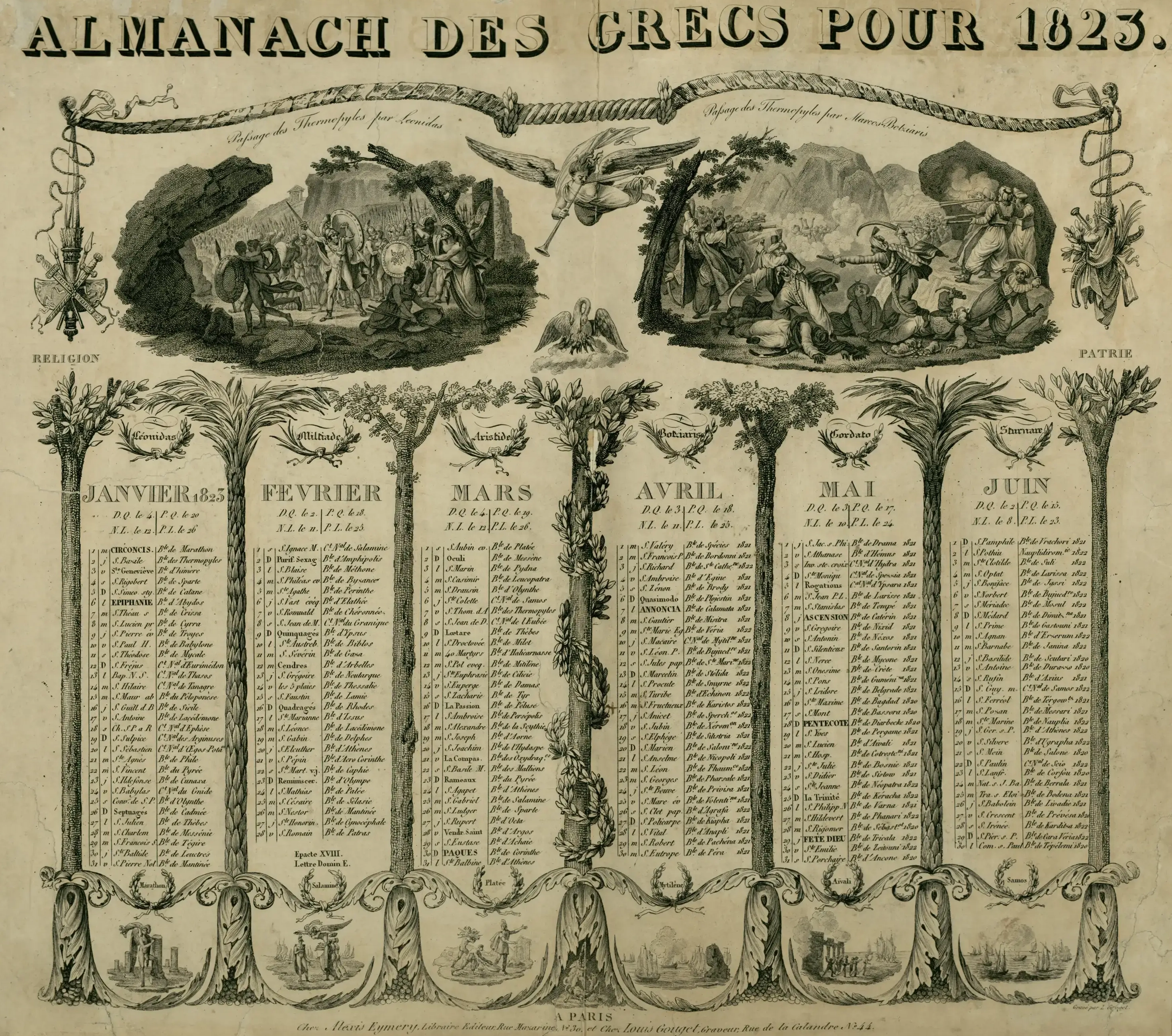

The Greek War of Independence (1821–1828) against the Ottoman Empire, the battles and their impact on public opinion, the heroes and leading figures of the Revolution, the organization of government, the national assemblies, the first printed books and newspapers,Philhellenism, as well as the earliest scholarly studies on the revolution of 1821, are all well represented in Gennadius’s collections. After all, the category “Independence” formed the very first volume of the typed catalog Gennadius prepared for his library in 1921. In fact, the scrapbooks dedicated to 1821 contain rare historical evidence on the Greek Revolution.

The first revolutionary stirrings emerged during the mature phase of the so-called Modern Greek Enlightenment in the second half of the 18th century, rooted in the idea of a modern Greek state connected to the ancient past. Central to the preparation for the revolution was the secret organization “Philiki Etaireia” (Friendly Society), founded in Odessa in 1814.

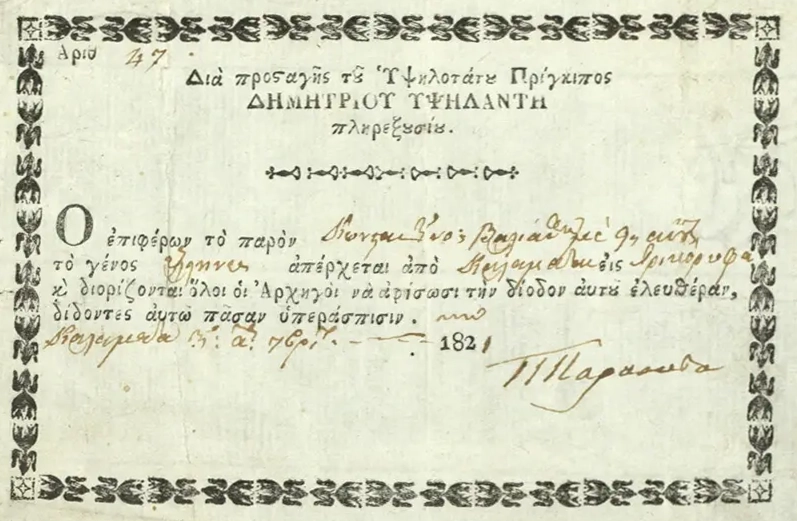

In February 1821, the leader of the “Philiki Etaireia”, Alexander Ypsilantis, crossed into the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and soon thereafter, revolutionary uprisings spread from Macedonia to Crete. On March 23rd, Kalamata fell to the hands of the Greek revolutionaries; one of the leaders of the Revolution, Petrobey Mavromichalis, established the “Messenian Senate” in the town of Kalamata. Later, Peloponnesian forces under Theodoros Kolokotronis besieged and occupied Tripolitsa. Despite all the disagreements and civil conflicts among the revolutionaries, a temporary central administration was formed, securing victories in the Peloponnese, Central Greece, and several Aegean islands.

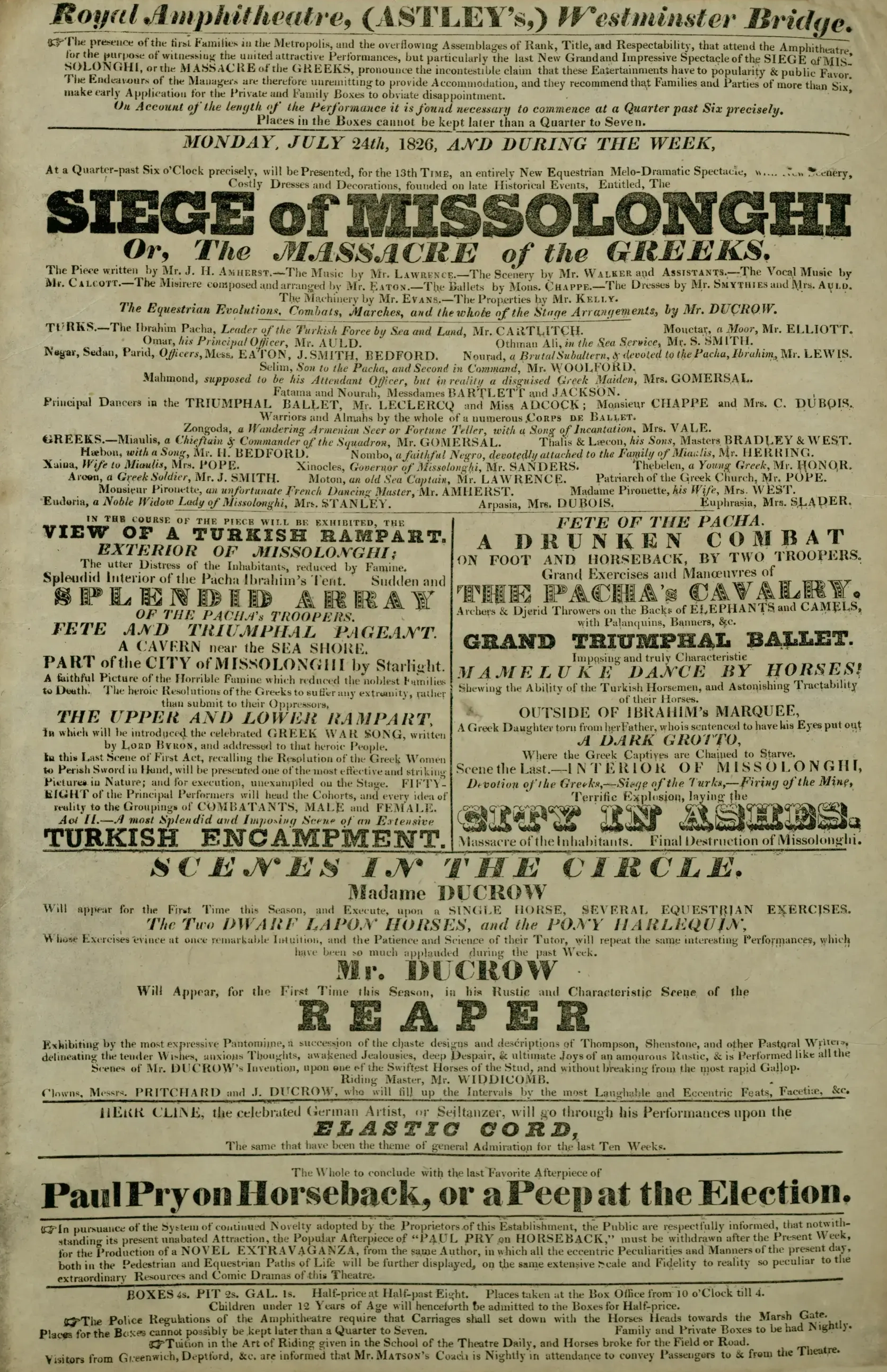

The Revolution’s success was imperiled in 1825, when Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt took military action. But the fall of Messolonghi in 1826, coupled with the growth of European Philhellenism, shifted the diplomatic stance of the European Great Powers, which had viewed the outbreak of the revolution with suspicion. The armed intervention of England, France and Russia at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, the French expedition to the Morea, and the Russo-Turkish War contributed decisively to the Greek cause.

In 1827, Ioannis Kapodistrias was elected the first Governor of the Greek State. Until his assassination in 1831, he worked tirelessly on internal reforms and the promotion of Greek interests abroad. Greek independence was formally recognized in 1830 with the London Protocol, and the borders of the new state were finalized in 1832 along the Ambracian Gulf–Pagasetic Gulf line. Greece became a monarchy under the Bavarian prince Otto.

Among the greatest treasures of the Gennadius Library is a series of paintings depicting battles of the Greek War of Independence. These paintings were commissioned by General Makriyannis from the Laconian painters Panagiotis and Dimitrios Zographos (1836–1839). The paintings, originally painted on wood, and later, on paper, were presented as gifts to King Otto and the rulers of the Great Powers. Today, only two of these four sets survive: the paintings from the Gennadius collection, which once belonged to King Otto, and the paintings offered to Queen Victoria of England, which are still preserved in Windsor Castle.

Equally important is the Byron collection, which preserves rare works and personal belongings of the poet, including his portrait and the laurel wreath entwined with wildflowers offered by the people of Messolonghi. Also of great value is the series of portraits by Adam Friedel, “Twenty-Four Portraits of the Principal Leaders and Personages who have made themselves most conspicuous in the Greek Revolution”.

The Gennadius Library, thus, offers a unique opportunity to discover rare evidence and rich bibliography relating to the course of modern Hellenism, making it an indispensable resource for the study of modern Greek history.

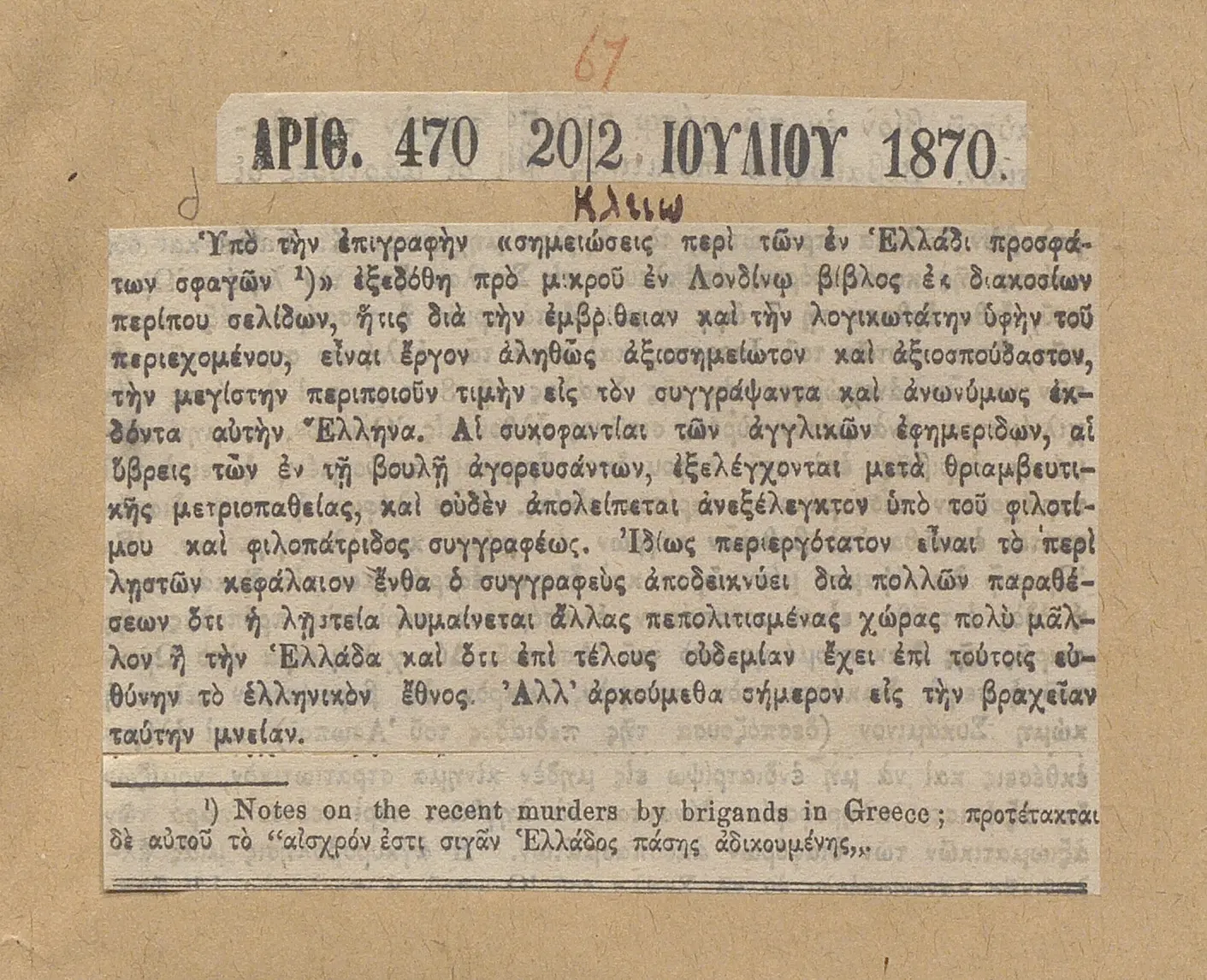

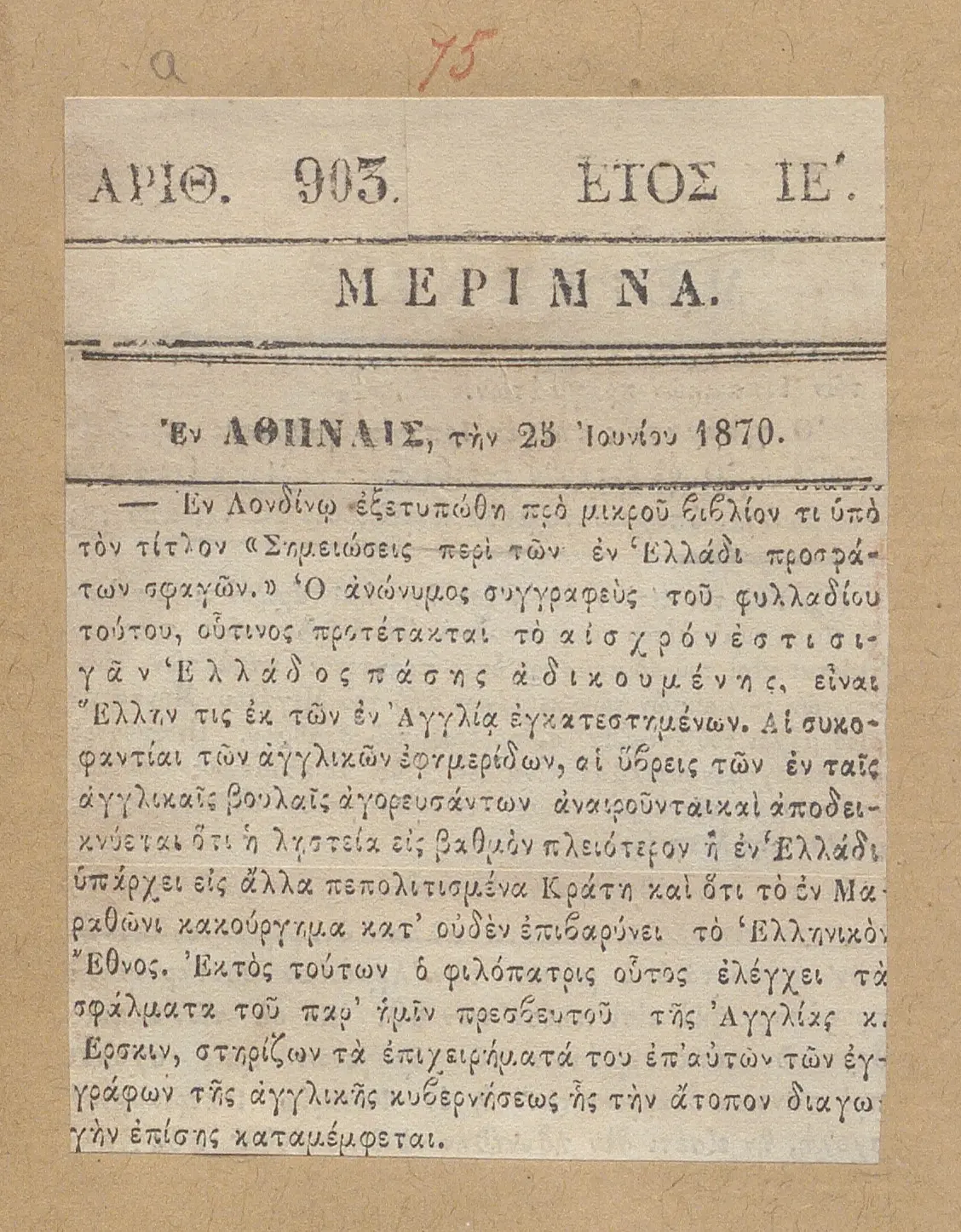

The Dilessi murders (1870)

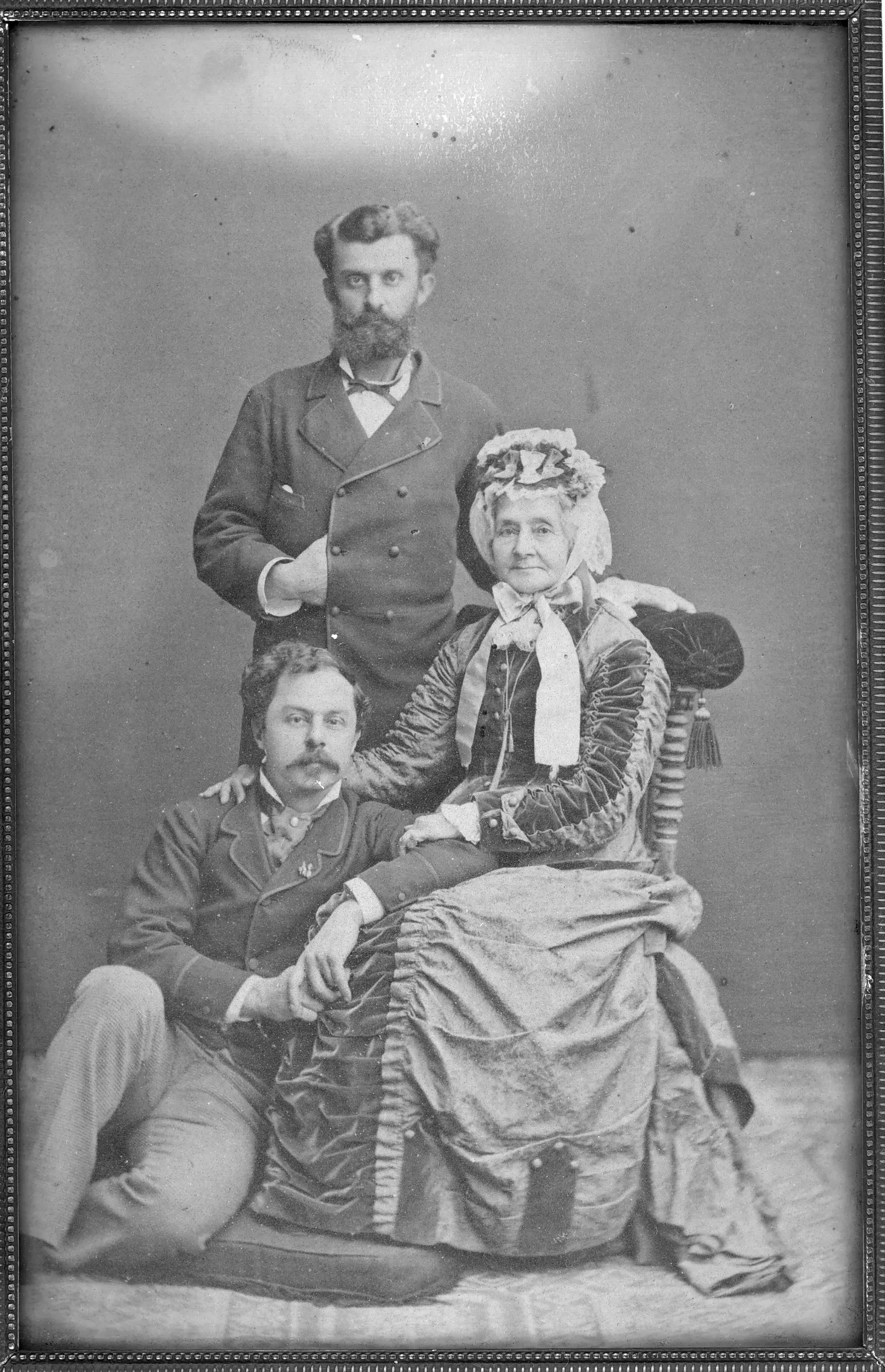

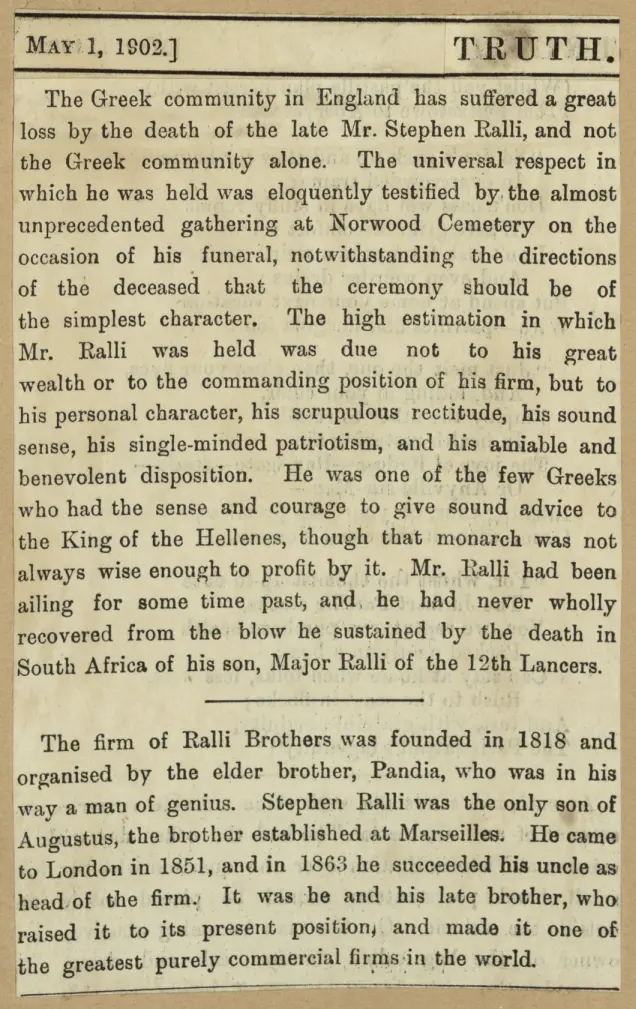

The shocking events known as the “murders of Dilessi or Marathon” (1870), deeply disturbed Joannes Gennadius, who had been living in London since 1862 employed by the prominent Greek firm of Ralli Brothers. There, he associated with young men of refinement, wealth, and influence. Yet, he was troubled by the prevailing pro-Turkish sentiment in England and by a general distortion of Greece’s image and values. He, therefore, made it his personal mission to defend his homeland. Under the pseudonym “Zeus’ Offspring” (Διός Γέννα), he wrote four letters to the liberal newspaper The Morning Star, setting out historical and statistical evidence of the rapid material progress of the Greek nation and the maturity of its citizens. All his letters were published, bringing recognition and satisfaction to the Greek community in London.

Despite Gennadius’s efforts, in April 1870 an incident intensified anti-Greek sentiment in western Europe: a band of brigands kidnapped a group of foreign tourists near Marathon. Some of them were British, and while negotiations for their release were underway, the murder of three of the captives provoked furious reactions and a surge of anti-Greek feeling in Western Europe, especially in Britain. The incident seemed to undermine Gennadius’s claims of Greece’s maturity and stability.

The British press stirred public opinion against the Greeks. The directors of Ralli Brothers, aware of the fervent patriotism of their employee Joannes Gennadius, warned him not to publish any statements in defense of Greece. Nevertheless, he considered it his “sacred duty” to set the record straight.

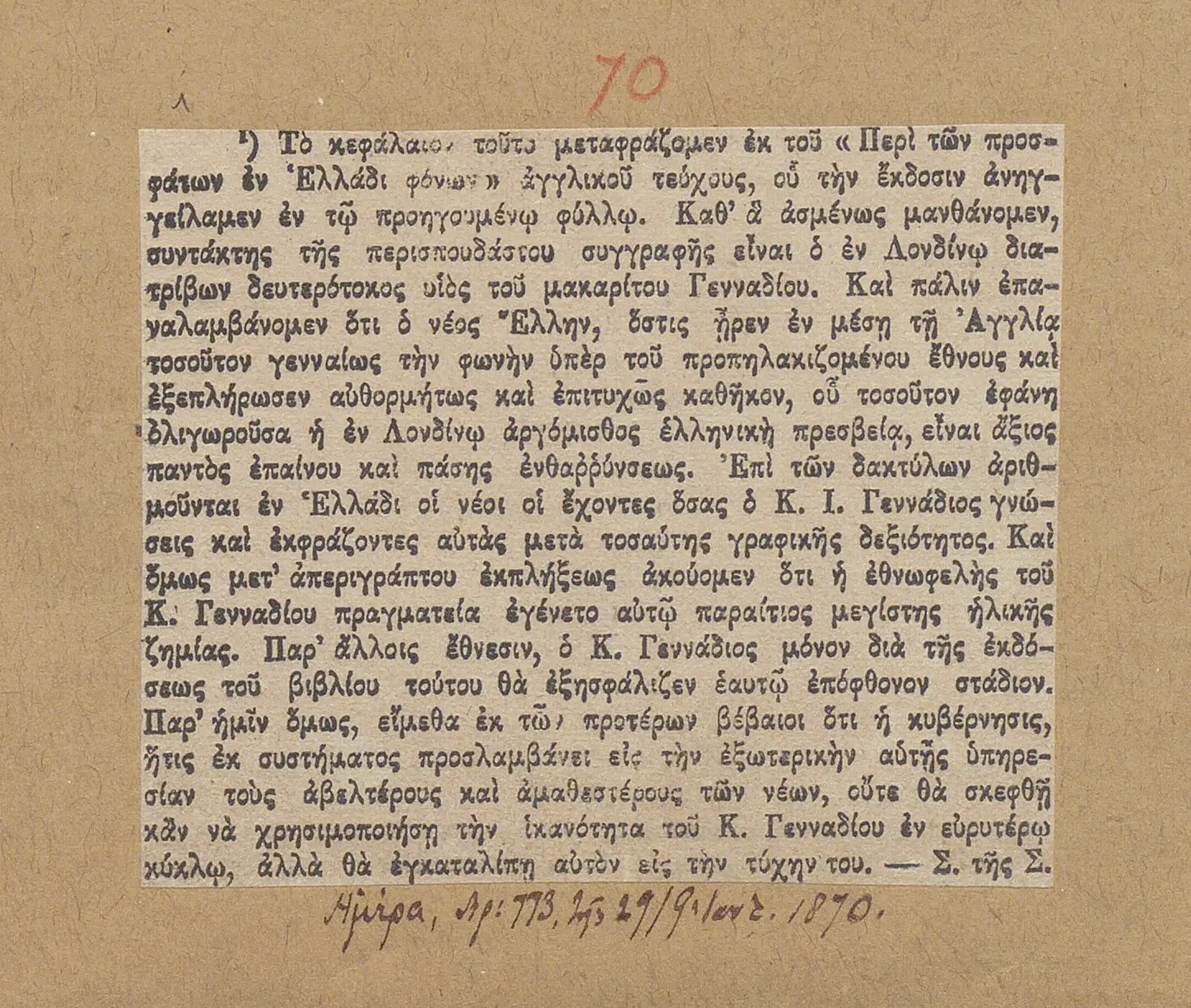

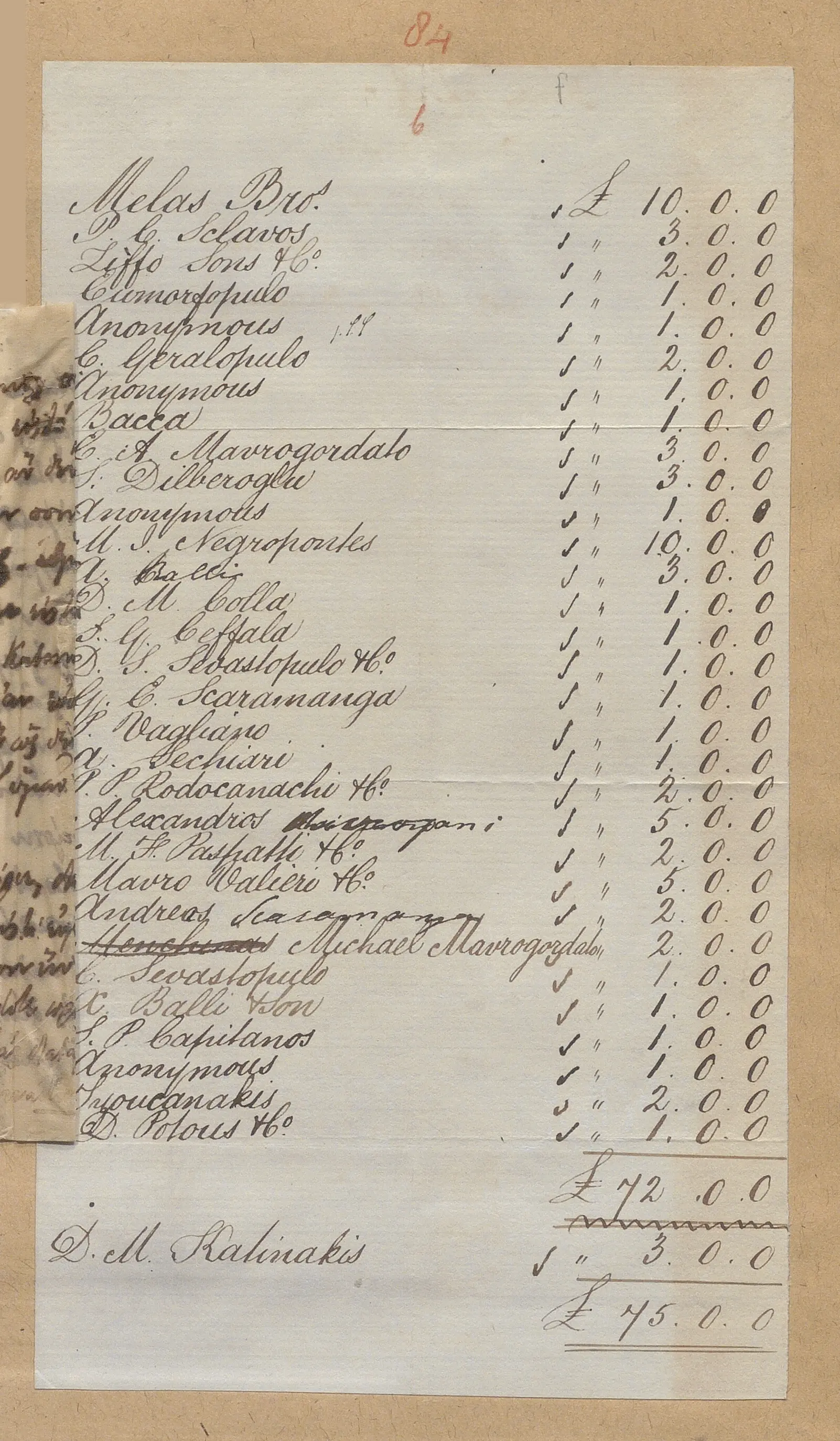

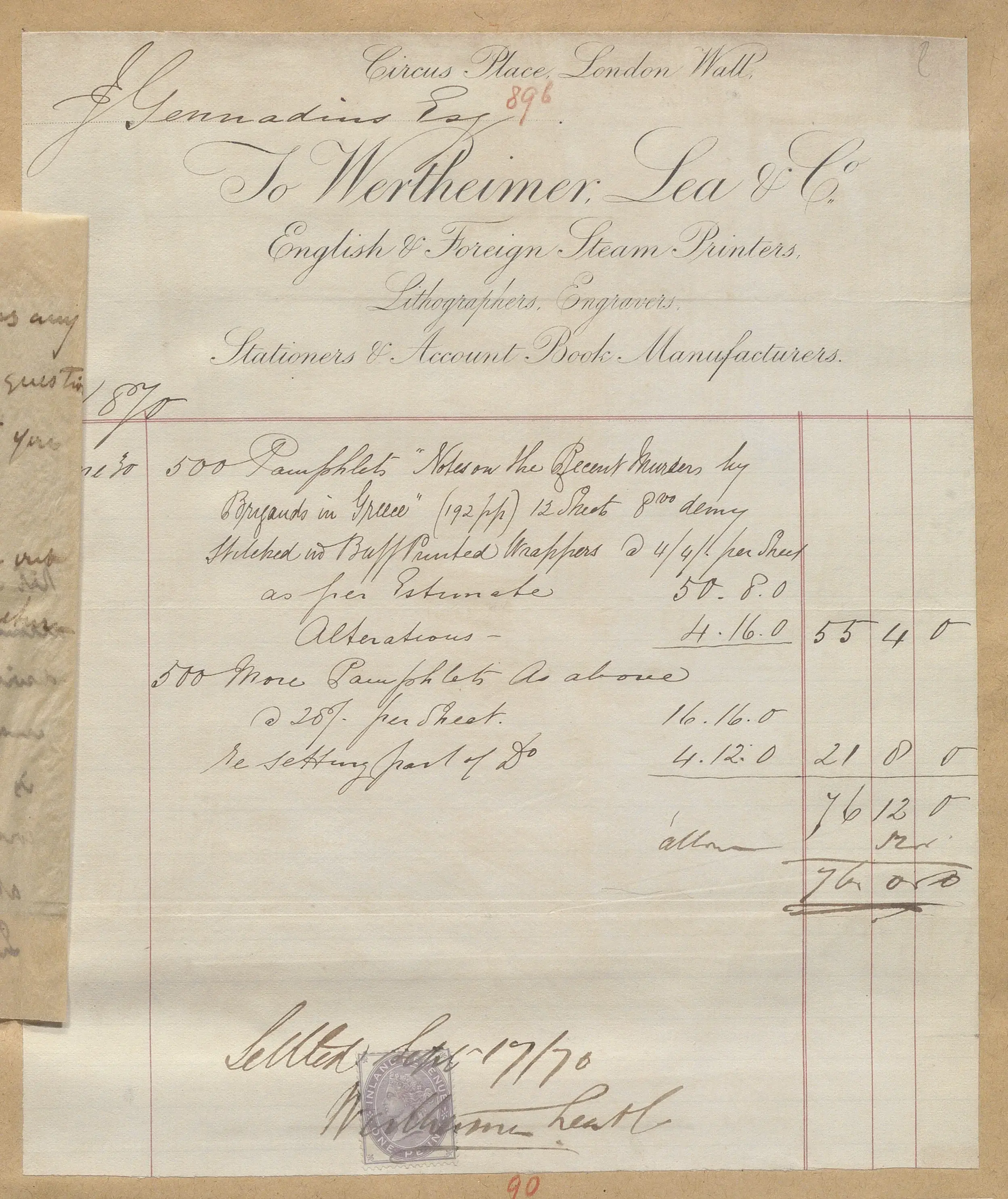

For about four weeks, Gennadius devoted all his free time to carefully investigating the events and circumstances of the “Marathon murders,” as well as patterns of criminality in other European countries. By the end of June, he had completed a “substantial pamphlet,” which he printed anonymously at his own expense. This large pamphlet, titled “Notes on the Recent Murders by Brigands in Greece,” concerned the massacre at Dilessi of three Englishmen and one Italian, who had previously been taken captive by local brigands. The aim of the pamphlet was not to absolve the Greek authorities of responsibility for their handling of the affair, but rather to counter the slanders—circulated chiefly through the British press and spread across Europe—that cast sweeping blame and heaped offensive remarks upon the Greek people.

Among Gennadius’s papers is a letter to the Greek Minister of Finance, Theodoros Deligiannis, dated November 6, 1871, regarding the government’s encouragement to have the pamphlet on the Massacre in Dilessi translated from English into Greek. Although the original English edition had been financed entirely by Gennadius himself, he was unable to cover the additional cost of a Greek edition. Consequently, at the ministry’s request, the translation was printed at the National Printing Office. Yet, due to a legal impediment preventing the publication of private works by the state press, the edition was stopped. Gennadius therefore appealed to the minister, clarifying that the work was not truly “private,” since the translation of the pamphlet served national interests and the defense of Greece’s position in the international sphere.

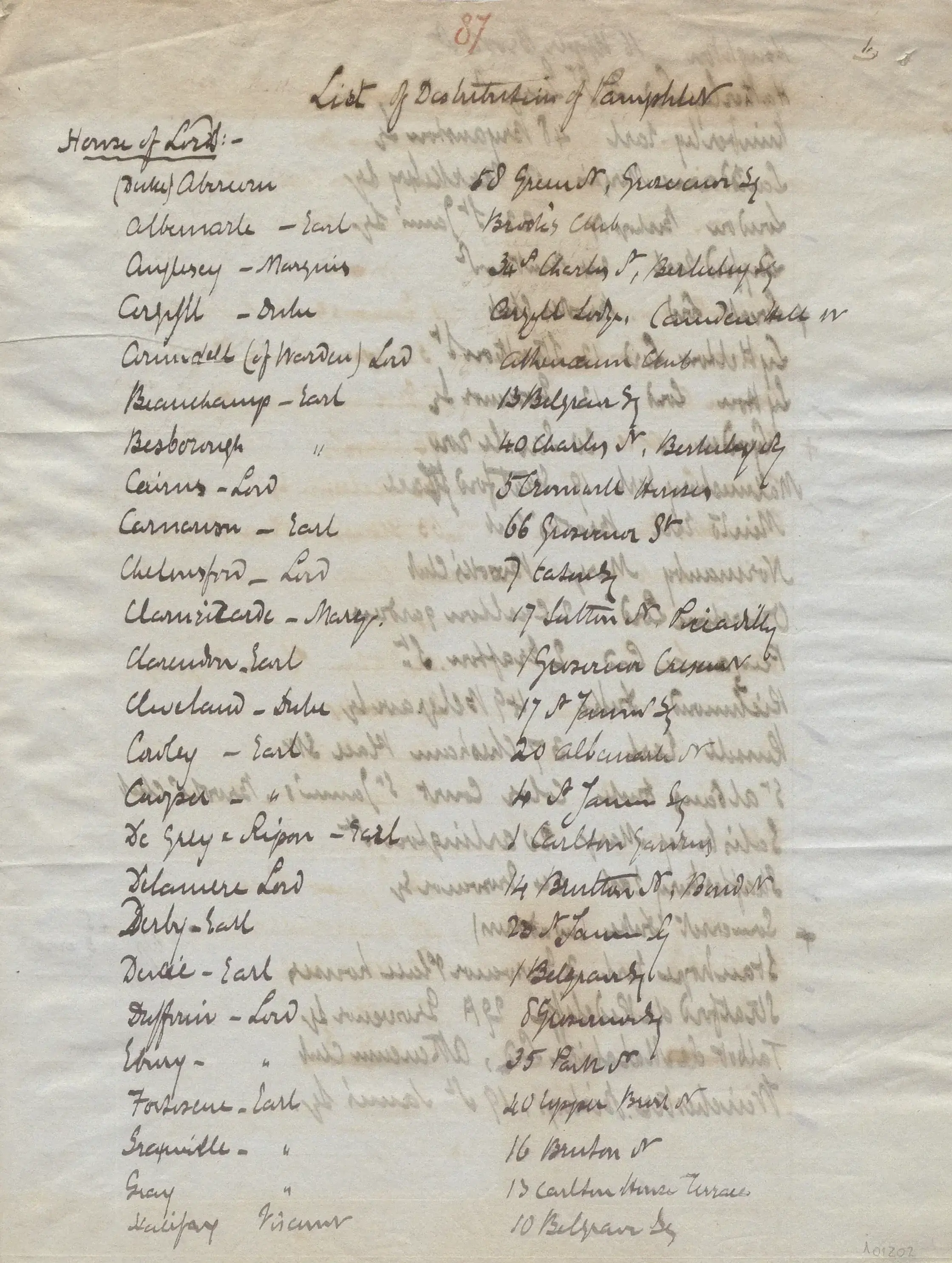

The matter was soon to be debated in the Parliament in London. Gennadius hired a cab and spent an entire night distributing his pamphlet to prominent members of both Houses of Parliament of England, to newspaper publishers, and to other public figures. The Greeks of London were very proud of the young compatriot who defended his homeland and its honor with such fervor. British reactions were mixed, however. The directors of the Ralli Brothers, feeling compelled to act in line with their earlier warnings, gave Gennadius six months’ notice to leave the firm.

His promising business career in England had come to an end. In Greece, however, he was regarded almost as a hero. The echoes of his father’s rhetorical gifts were evident in his passionate defense of Greece and the Greeks. This ultimately led him to fulfill the early expectations of his family by entering the Greek Diplomatic Corps.

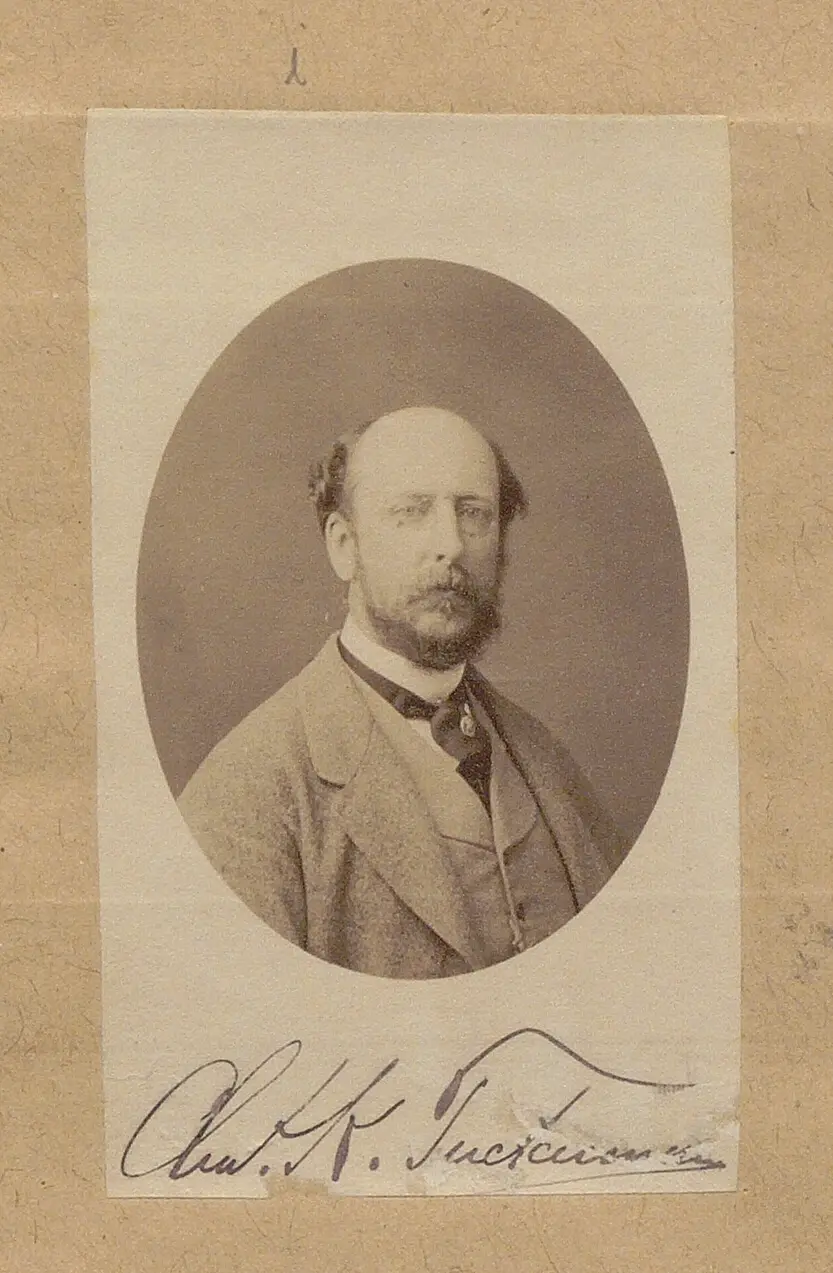

In November 1870, he was appointed Attaché to the Greek Diplomatic Mission in Washington, following a recommendation to the Greek government by Charles Tuckerman, U.S. Minister in Athens, who had been especially impressed by the “substantial pamphlet.” Among Tuckerman’s reports and publications in support of the Greek cause is a document entitled “Brigandage in Greece. A Paper Addressed by Mr. Chas. K. Tuckerman, United States Minister at Athens, to Mr. Fish” (December 5, 1870), concerning the issue of brigandage in Greece. In it, he analyzed the problem of brigandage from its origins in the Greek Revolution and the “klephts,” concluding that certain groups continued similar practices in a different context. He pointed out the difficulties of addressing the issue, due to a kind of enforced protection or “compulsory friendship” between mountain populations and the brigands. In return for protection and occasional financial support, villagers were bound to warn the brigands if the authorities sought them. At times this “cooperation” was compelled by threats of raids against the villages. The same logic governed relations between local political candidates and the brigands, since “non-cooperation” could prove harmful and dangerous not only to the politicians and their families but also to the wider community.

At first, the author of the pamphlet remained anonymous. In due course, however, it became known that the controversial work had been written by Joannes Gennadius. Praiseful commentaries soon followed, praising the young Greek who, inspired by patriotism and a strong sense of national duty, had so ably defended his country’s cause. The story continued to attract press attention, which criticized Joannes Gennadius’s employer, Mr. Ralli, for the unacceptable stance of dismissing him merely because he had written a political pamphlet. The style and arguments presented in the pamphlet—funded entirely at Gennadius’s own expense—were themselves the subject of admiration, and the matter stirred debate both in Greece and abroad, even reaching the House of Lords in Britain.

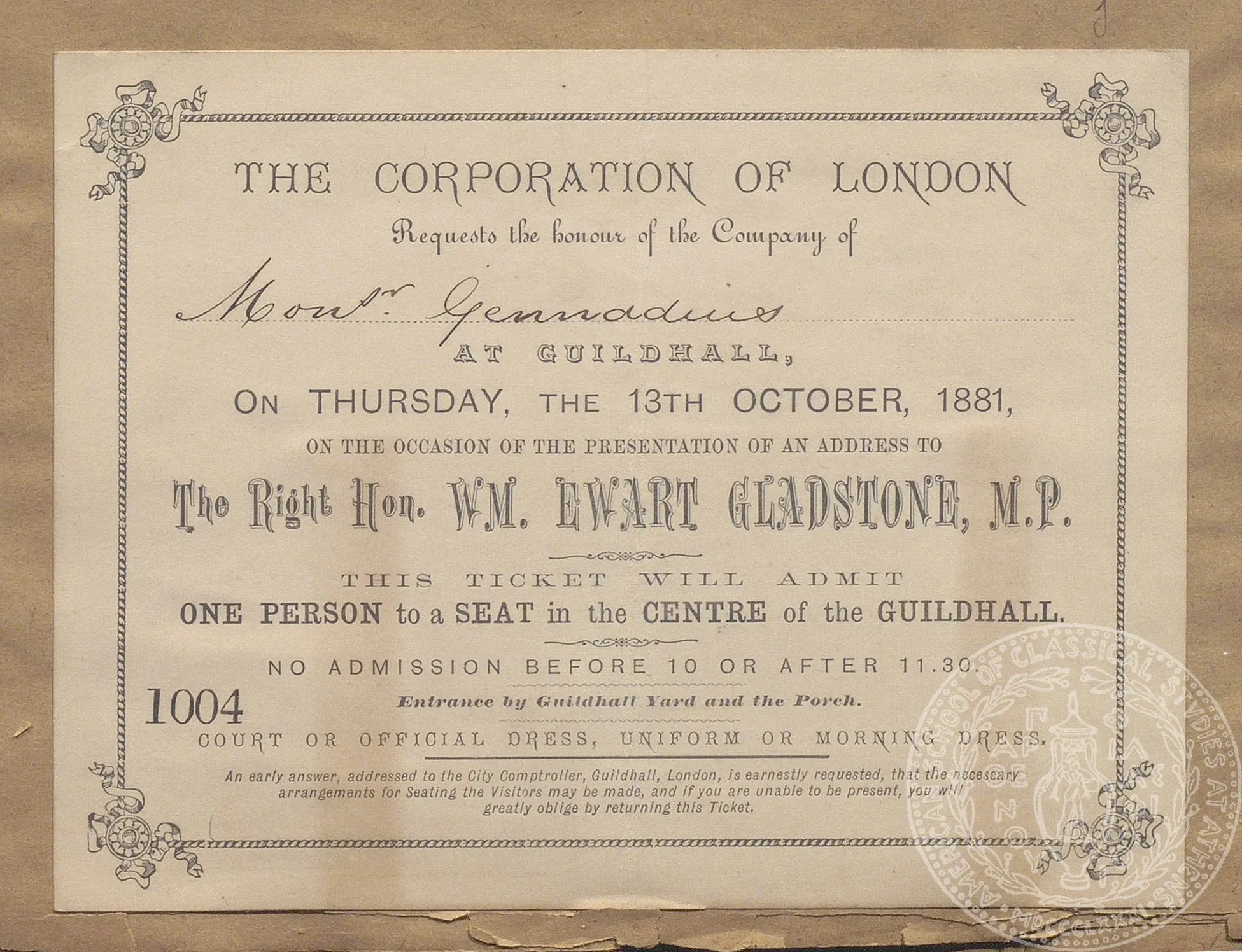

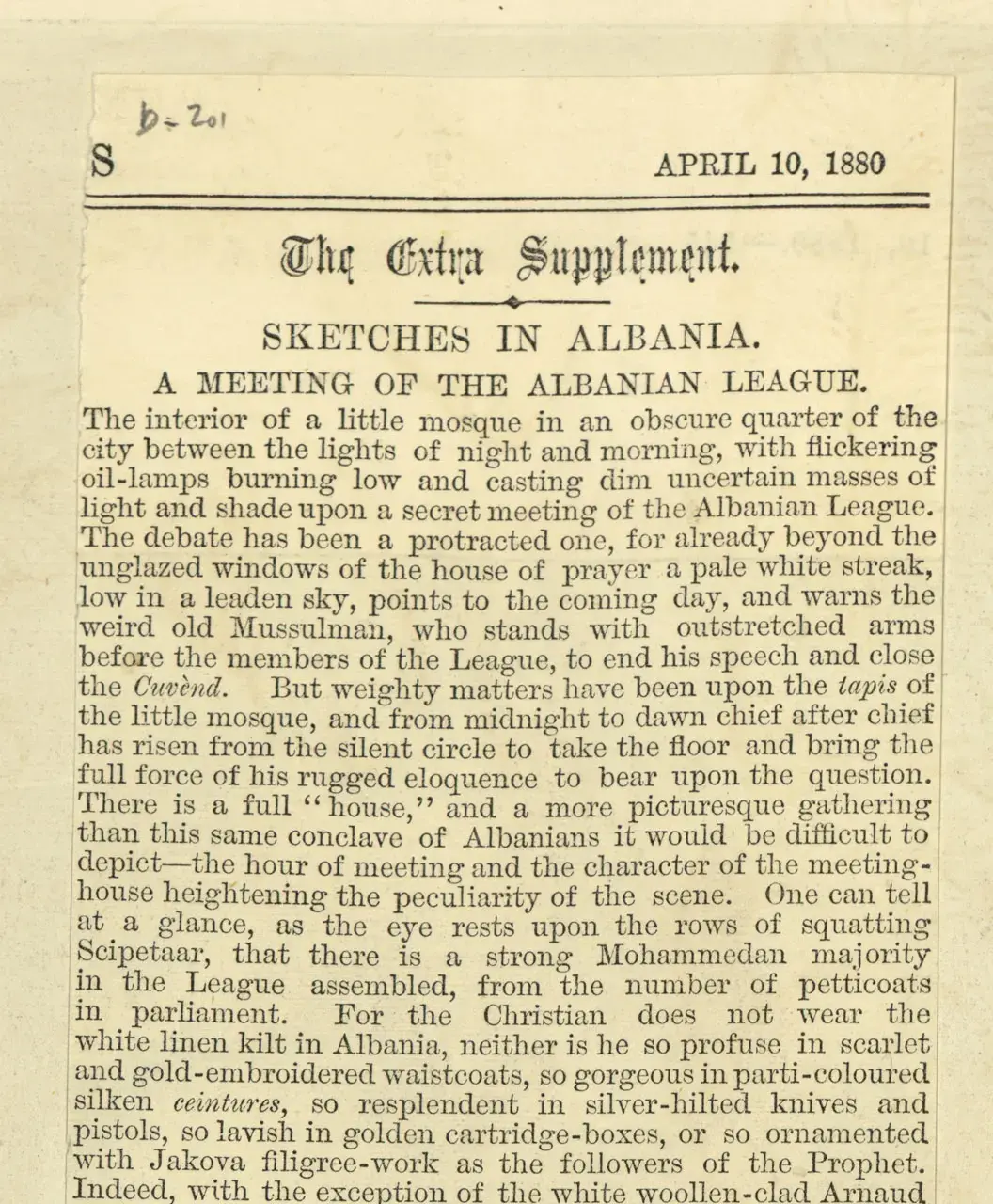

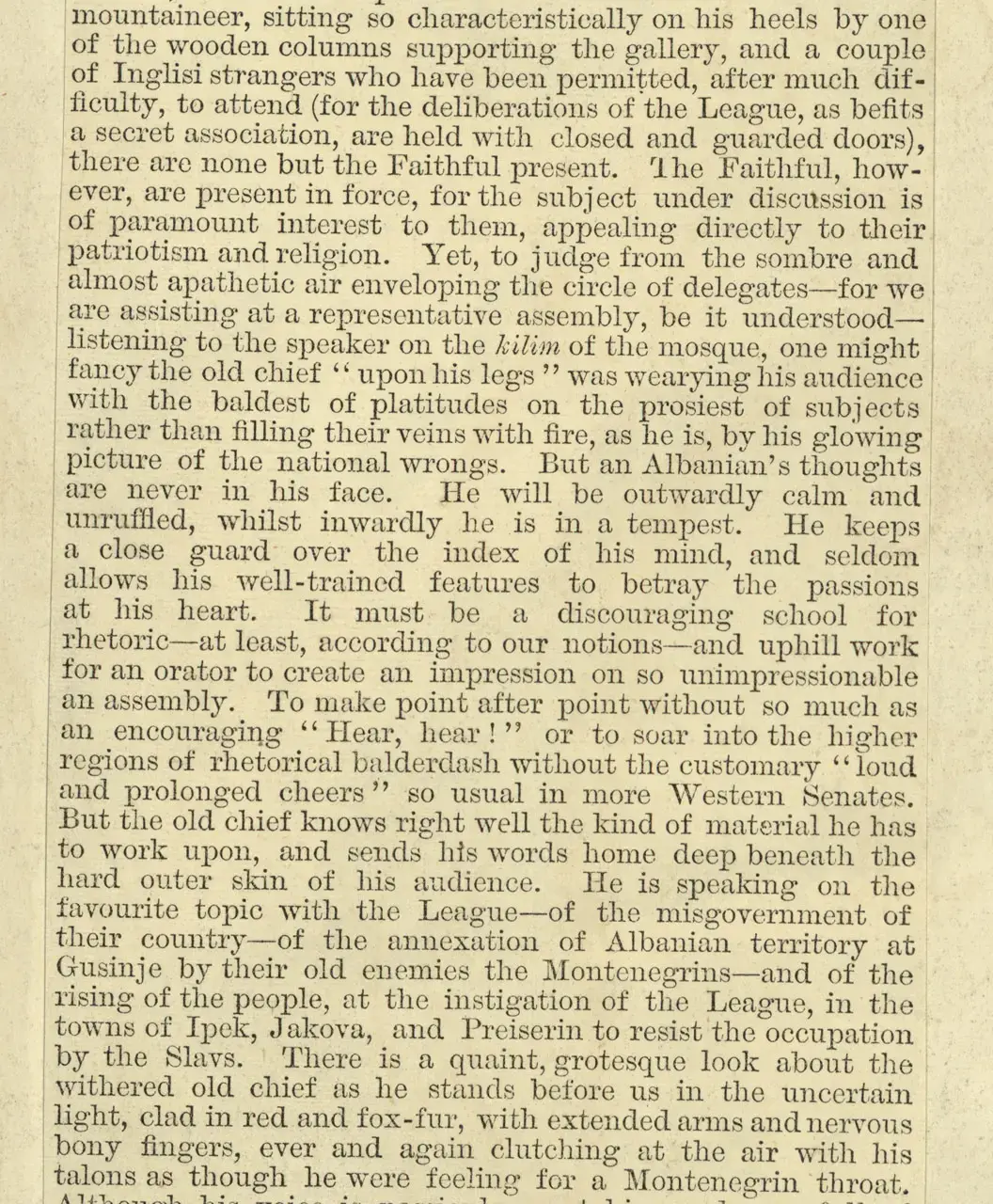

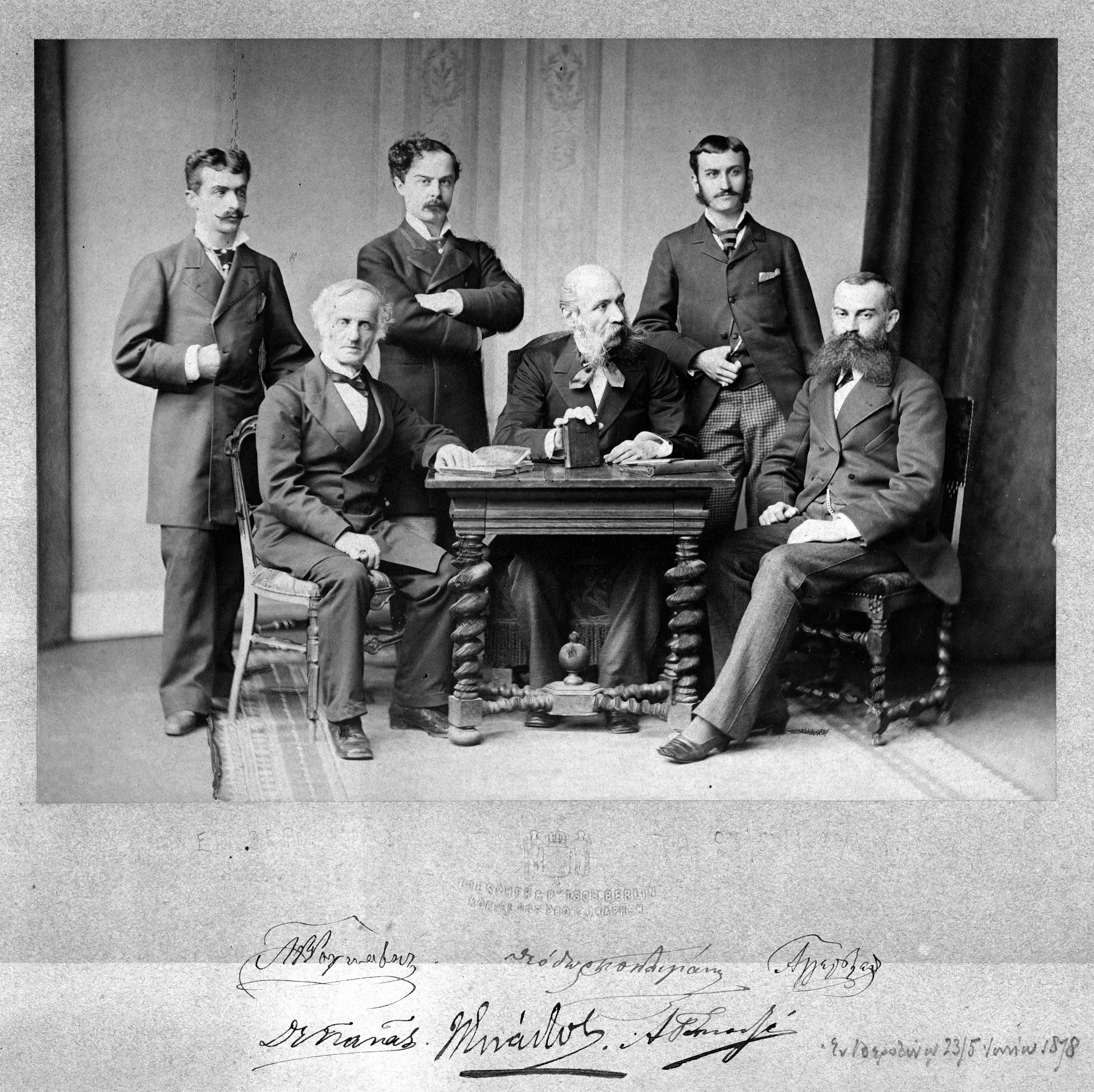

The Treaty of Berlin (1878)

In April 1875, Gennadius was sent to London as First Secretary of the Greek Legation and, very soon afterward, following the recall of the Chargé d’Affaires to Athens, he was promoted to the rank of Chargé d’Affaires in London. He was only thirty-one years old, but so successful that his government did not consider it necessary to appoint a more experienced representative. Relations between Greece and Britain improved and grew more cordial.

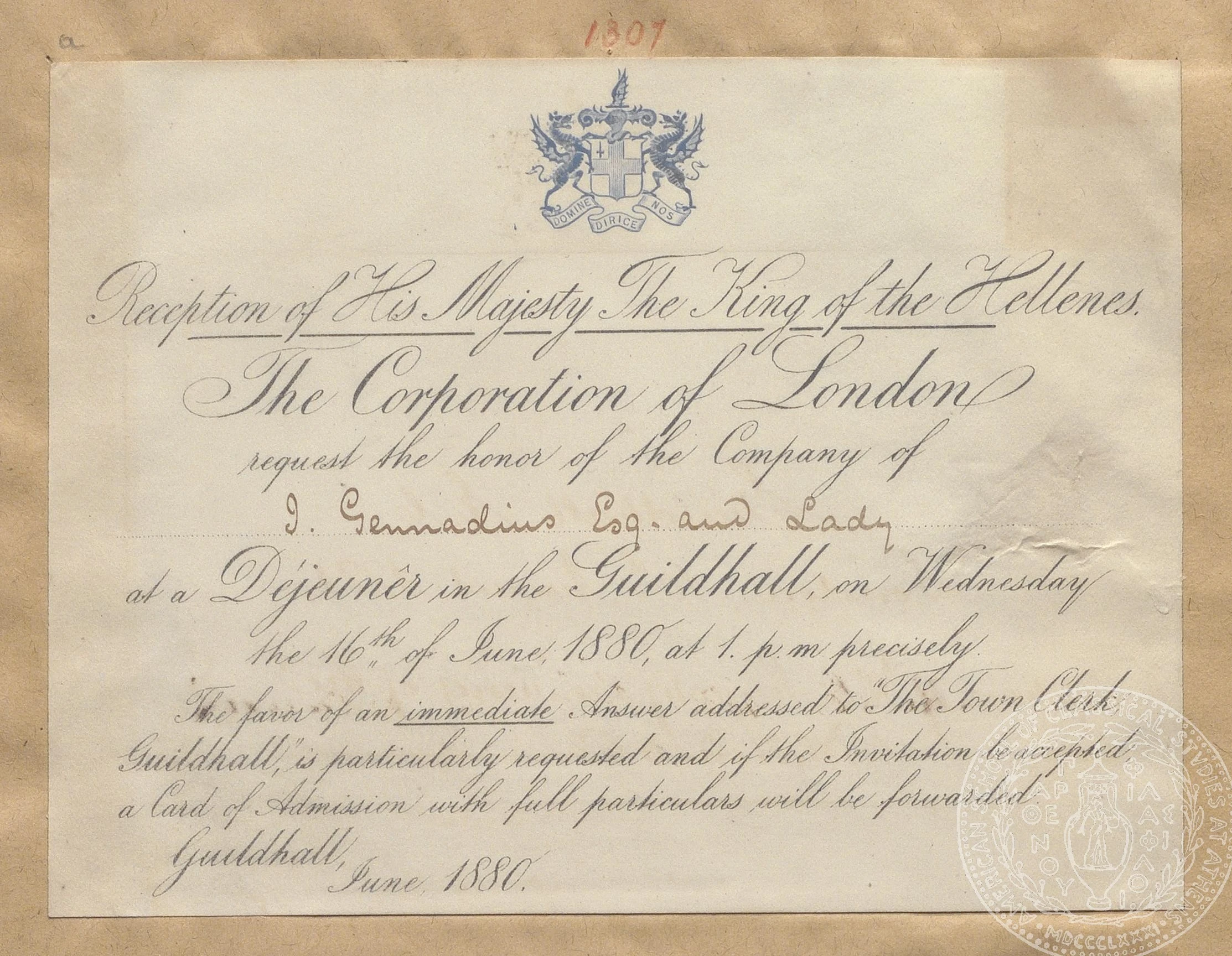

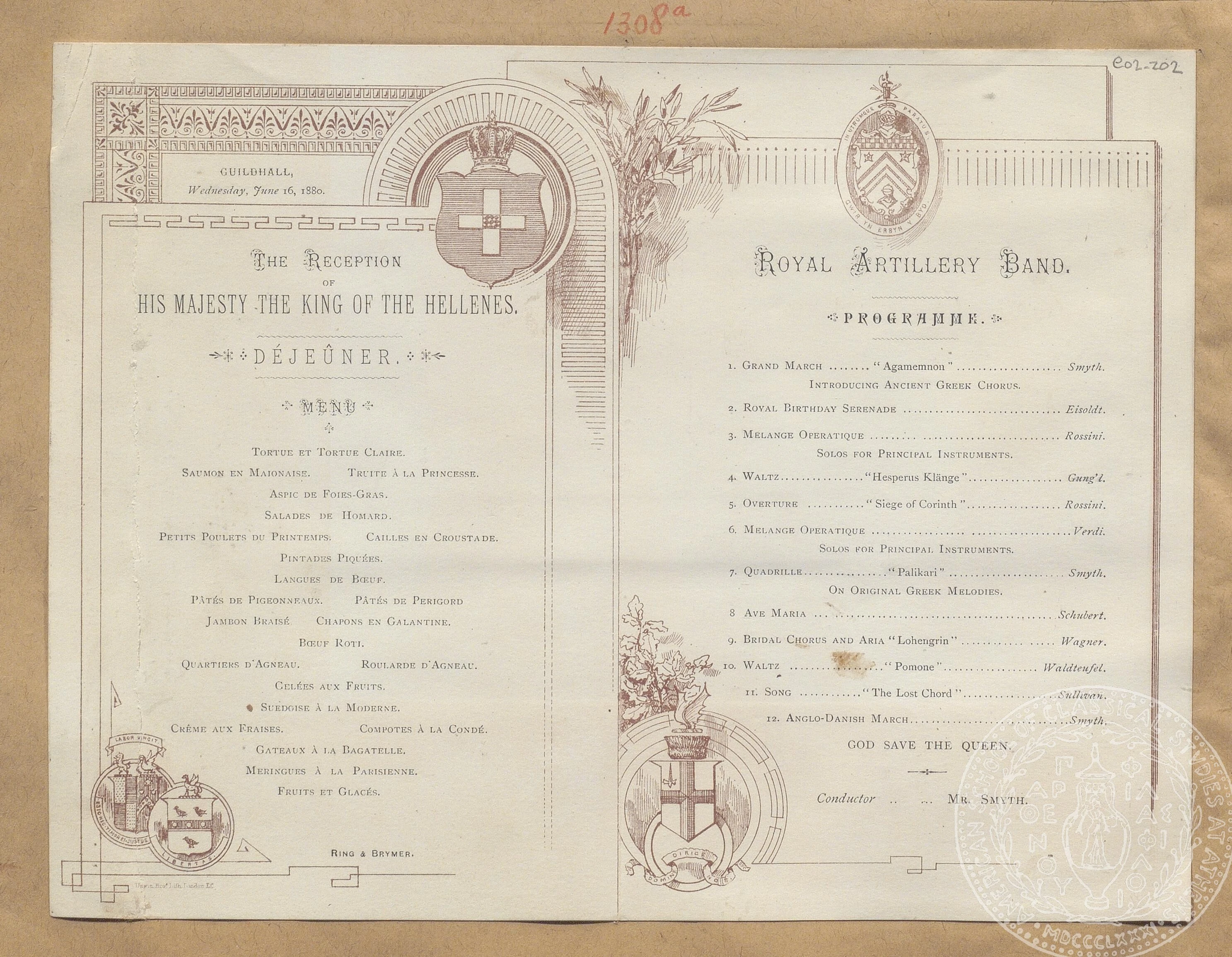

King George I of the Hellenes visited London in 1880 as part of the political developments concerning the Greek Question, and specifically the Greco -Turkish border dispute, which was at that time the subject of discussion at the Congress of Berlin.

The Treaty of Berlin (1878) established new borders between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, much to the Ottomans’ disappointment. Between 1878 and 1881, Greece engaged in a diplomatic struggle to secure the implementation of the Congress’s decisions. In this context, Gennadius promoted the creation of a Greek Committee in London to defend Greek interests. Lord Rosebery was appointed president of the Committee, whose members included all the leading figures of the Liberal Party. At the same time, Gennadius had the support of William Ewart Gladstone, who in 1879 published an essay entitled “Greece and the Treaty of Berlin.” By then, Gennadius had high expectations that the Athens government would recognize his evident success and popularity in London, and that he would be promoted to the post of Minister Plenipotentiary. In 1879 he had the honor and satisfaction of receiving from King George I the Grand Cross of the Order of the Savior.

Although the Congress of Berlin dealt a heavy blow to Pan-Slavism, it did not resolve the regional question. The Slavs of the Balkans remained for the most part under the sovereignty of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. In practice, the Balkan Slavic states learned that their unity as “Slavs” did not serve them as well as accommodating the wishes of a neighboring Great Power—undermining Balkan Slavic cohesion and fueling competition among the newly established Slavic states.

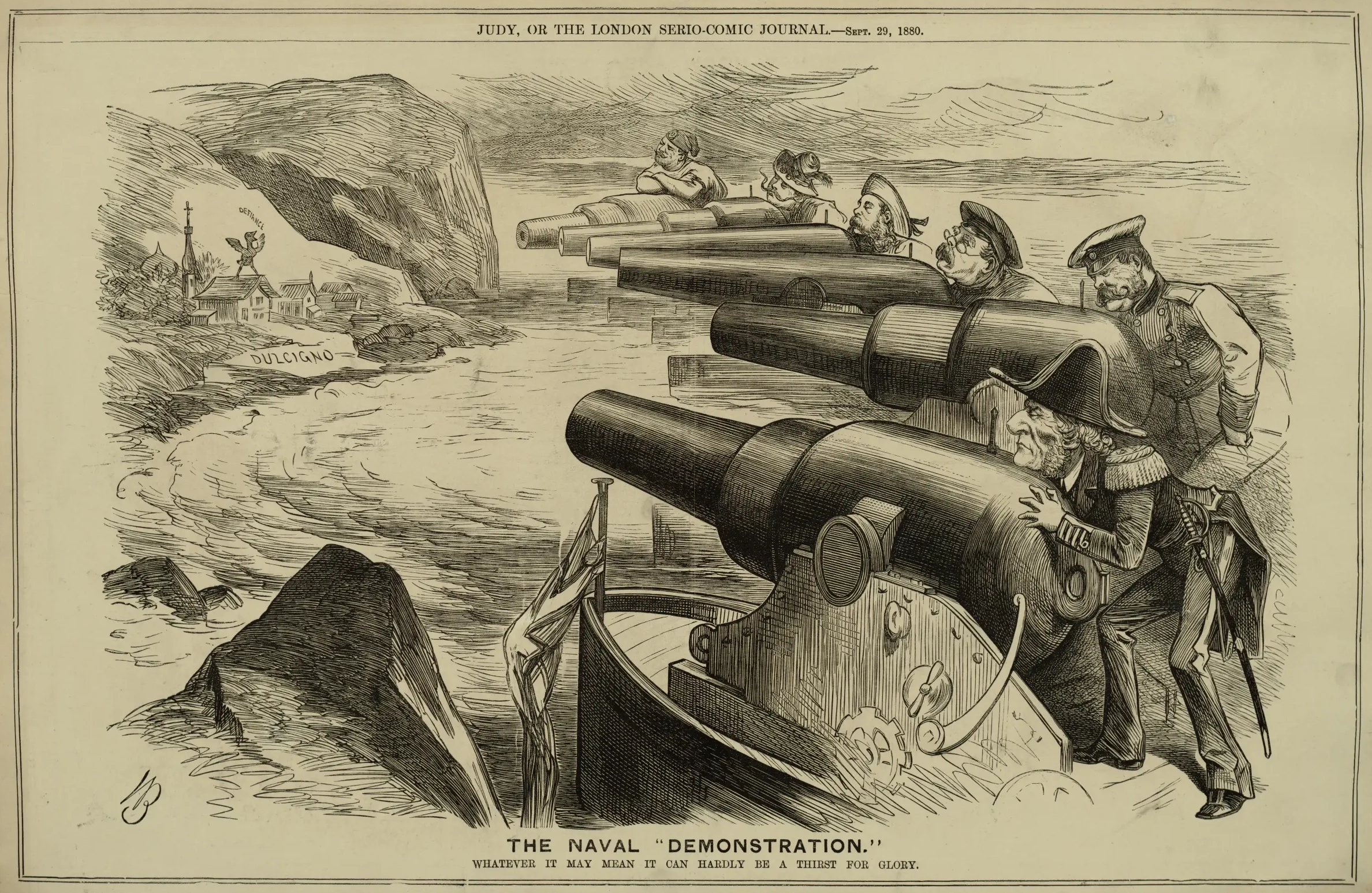

Regarding the border between Albania and Montenegro, as defined by the Treaty of Berlin (13 July 1878), the area of Dulcigno (Ulcinj) on the Adriatic—regarded by the Albanians as part of their national territory—was handed over to Montenegro. This decision provoked the reaction of the Albanian tribes, supported by the Sultan. The Great Powers attempted to enforce the Treaty’s provisions by dispatching a naval force to the Adriatic, but without success. Ultimately, Gladstone’s diplomatic pressure — notably his threat to take control of the Smyrna customs office — compelled the Ottomans to withdraw their support from the Albanian movement.

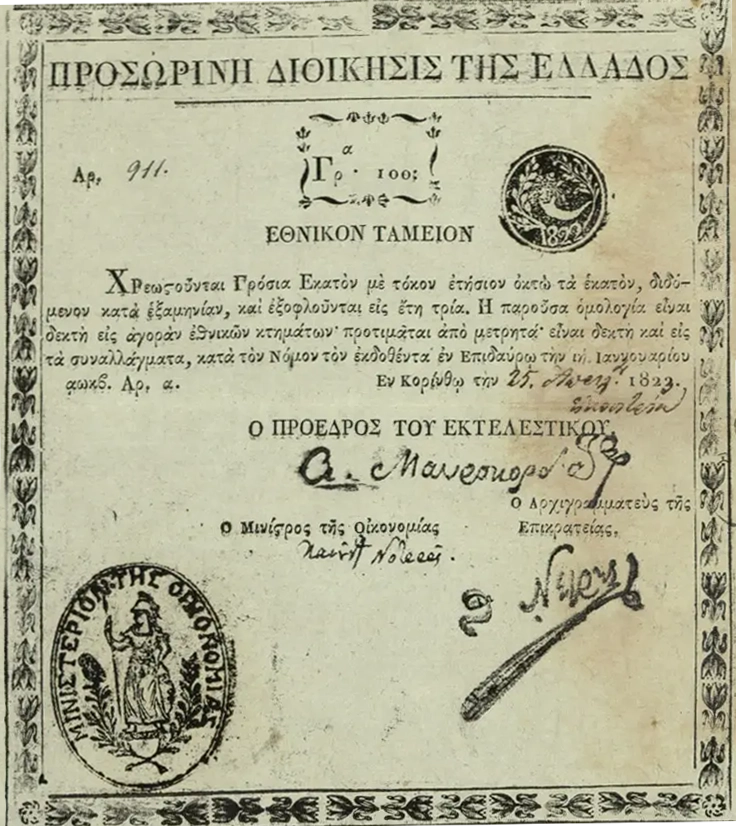

The Greek Independence Loans (1879)

Gennadius consolidated his position at the London embassy, where he participated with zeal in the social and political life of the city.

One of Gennadius's major achievements after returning from the Congress of Berlin was the settlement of the problem of the so-called “Independence Loans,” granted to the Provisional Government of Greece by British lenders in 1824–1825. He rightly foresaw that restoring Greece’s creditworthiness in the market would greatly strengthen British confidence in the country. After extensive negotiations with all interested parties—especially with the Dutchman Louis Drucker, who had agreed to purchase two-thirds of the original interest-bearing notes—a settlement was reached that was satisfactory to all but the Dutch.

With boldness, Gennadius brought the matter before the board of the London Stock Exchange. The notes issued fifty years earlier were converted into new ones, Greece’s credit standing was restored in the British market, and in 1879 he was able to announce that Greece had once again secured its place among the financially reliable nations.

The Revival of the Olympic Games (1896)

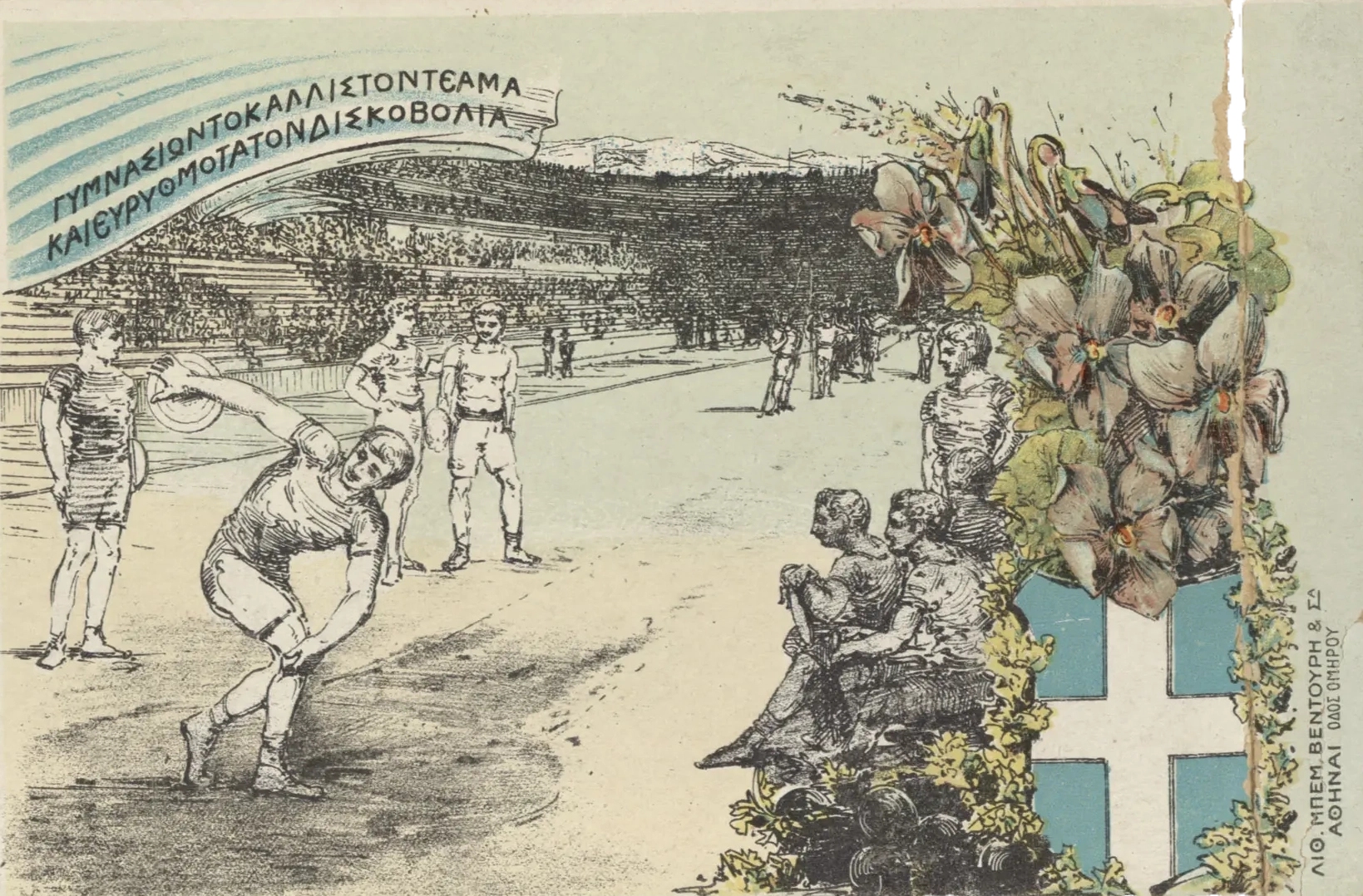

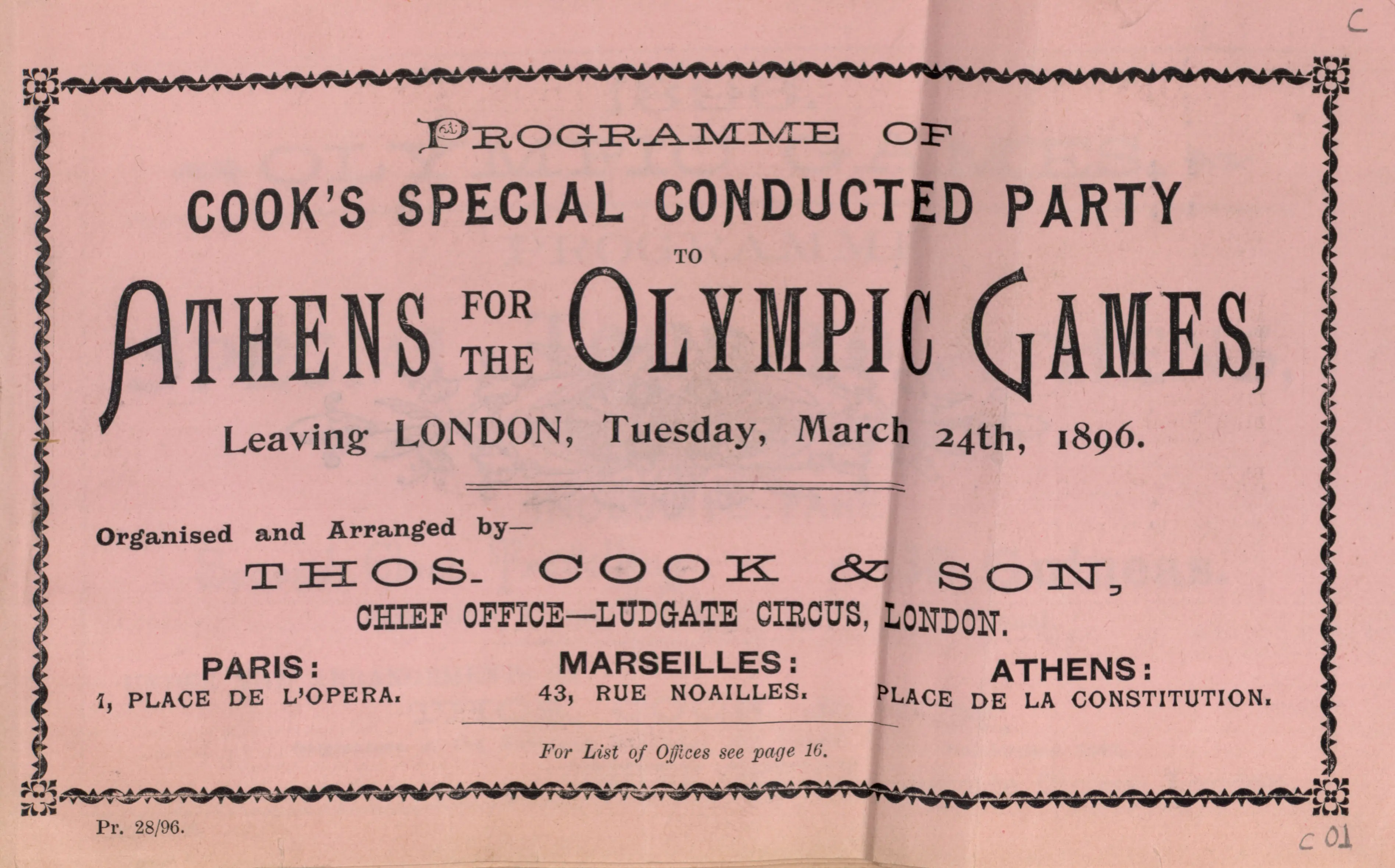

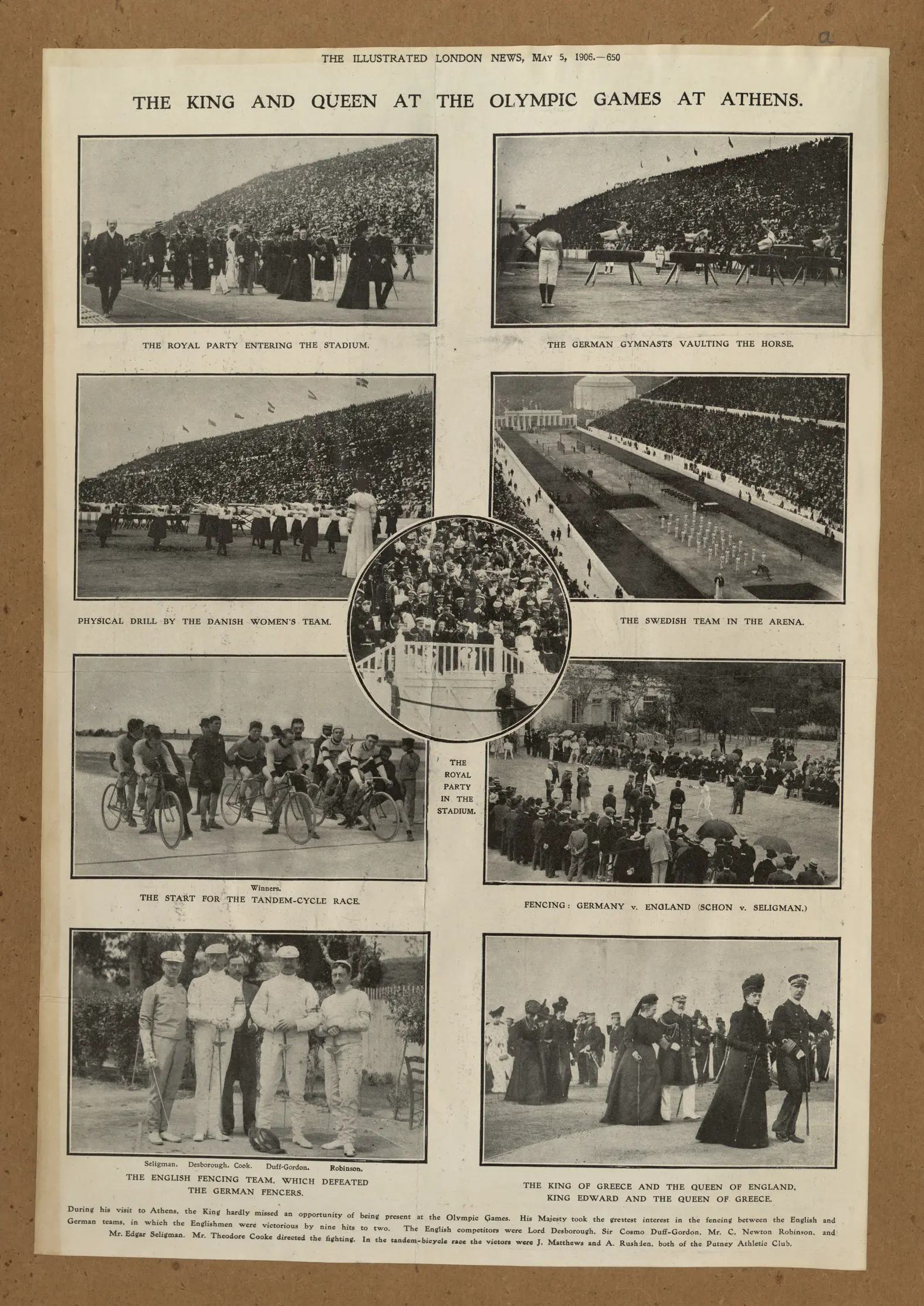

The Olympic Games of 1896 were the first international Olympic competition since their revival in modern era. They were held in Athens from April 6 to 15, 1896 (March 25–April 3 under the Julian calendar). See more photographs and films of the 1896 Olympic Games.

During the 19th century, several small-scale athletic festivals across Europe were regarded as continuations of the Ancient Olympic Games. Baron Pierre de Coubertin had been inspired by the Zappas Olympics (Olympia), funded by Evangelos Zappas and held in 1859, 1870, 1875, and 1888–1889. The revival of the Games in Athens was decided at the initiative of Coubertin and the Greek delegate Demetrios Vikelas.

The central venue of the Games was the newly renovated Panathenaic Stadium, where the athletics, weightlifting, gymnastics, and wrestling competitions were held, as well as the opening and closing ceremonies. The road cycling race and the marathon started from Marathon, while all swimming events took place at the Bay of Zea. Other venues included the Zappeion (fencing), the Neo Faliron Velodrome (track cycling and some tennis matches), the Kallithea Shooting Range (shooting), and the Athens Lawn Tennis Club (tennis).

The Games were a great success and drew large crowds of visitors, particularly at the opening ceremony in the Panathenaic Stadium (60,000 attendees). Although the number of athletes (241) seems small today, it was the largest international athletic gathering up to that time. All participants were European or resided in Europe, with the sole exception of the team from the United States. Greeks made up 65% of the athletes. Ten out of the fourteen participating nations won medals. The United States claimed the most gold medals (11), while the host nation Greece won the most medals overall (46). A landmark moment for the Greeks was Spyridon Loues’s victory in the marathon. The most successful athlete of the Games was the German wrestler and gymnast Carl Schuhmann, who won four gold medals. Watch the video

Members of the Greek royal family played a central role in organizing and managing the Games. After their conclusion, King George I, as well as many others (including American athletes), supported the idea of holding the next games in Athens. Coubertin, however, opposed the idea, as Paris had already been chosen as the next host city. The Games of 1900 therefore took place in France. Greece went on to host the Intercalated Games of 1906.

The Panathenaic Stadium, originally built around 330 BCE, had been excavated but was in ruins before the 1896 Games. Under the direction and with the financial support of George Averoff, a wealthy Greek from Egypt, it was restored with white marble.

Learn about the prize Spyridon Loues received from King Constantine by watching this video.

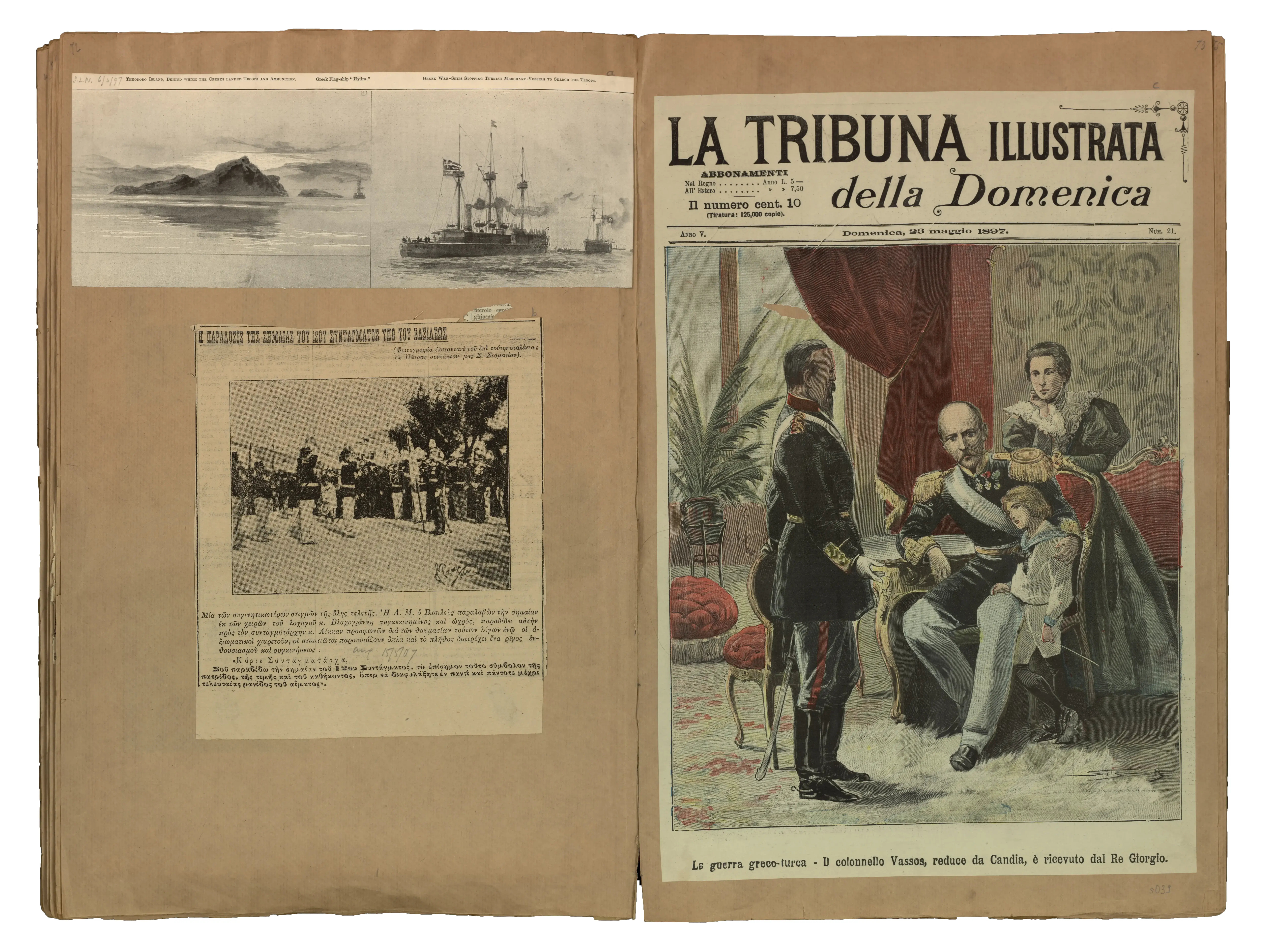

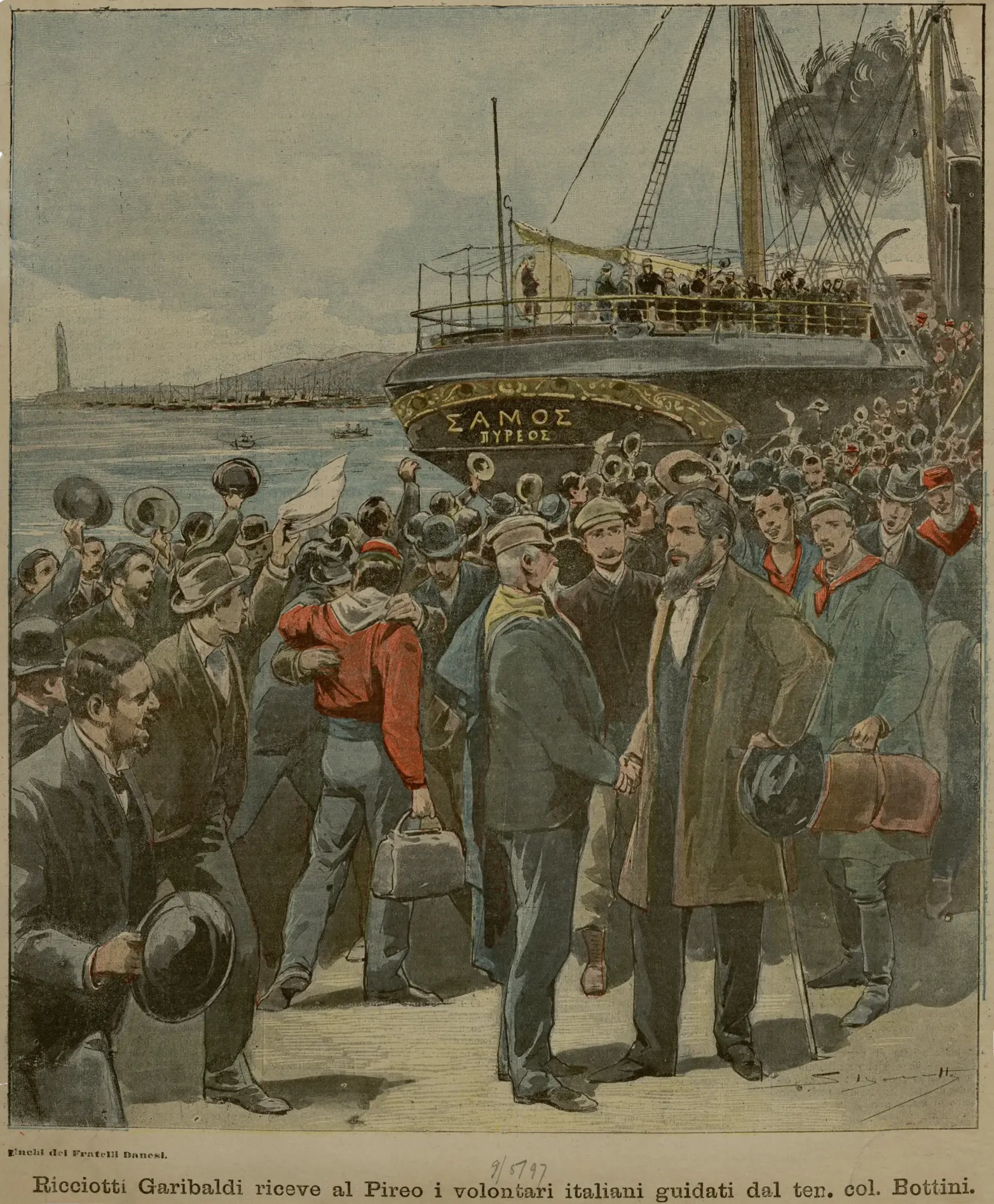

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The reason for the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 was the Cretan Question. According to the decisions of the Congress of Berlin (1878), the Ottoman Empire was obliged, among other things, to implement the Organizational Law of 1868 (known as the Halepa Convention). Non-compliance with the Halepa Convention led to uprisings, the most significant being that of 1896, which resulted in massacres of the Christian population in Chania in January 1897 and provoked the involvement of both the Great Powers and Greece. The intense diplomatic maneuvering, the humiliating—at least for Greece—decisions of the Great Powers, together with Greece’s diplomatic isolation and the revolutionary agitation fueled by the activities of the National Society in Athens, made war with Turkey all but inevitable.

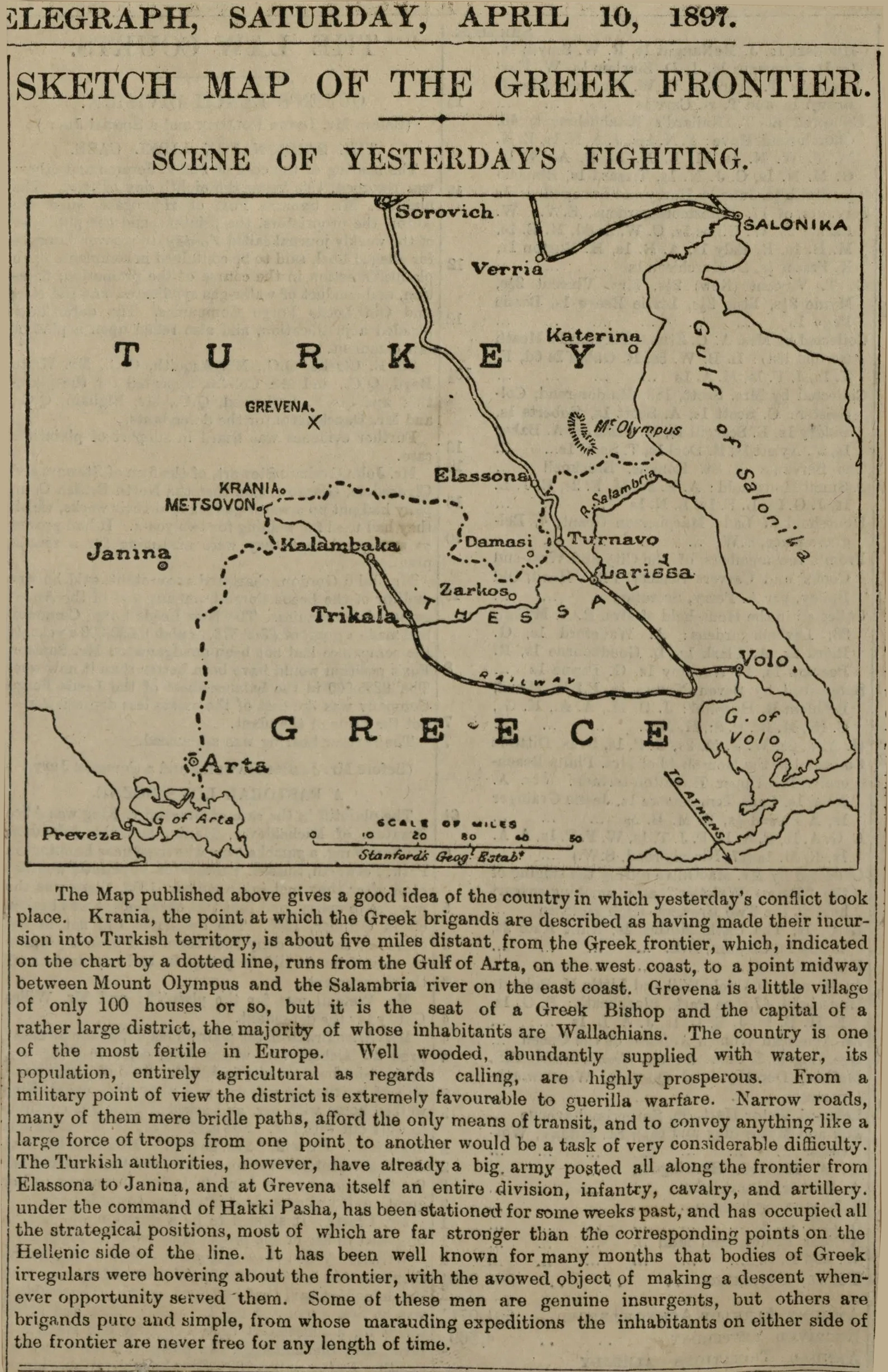

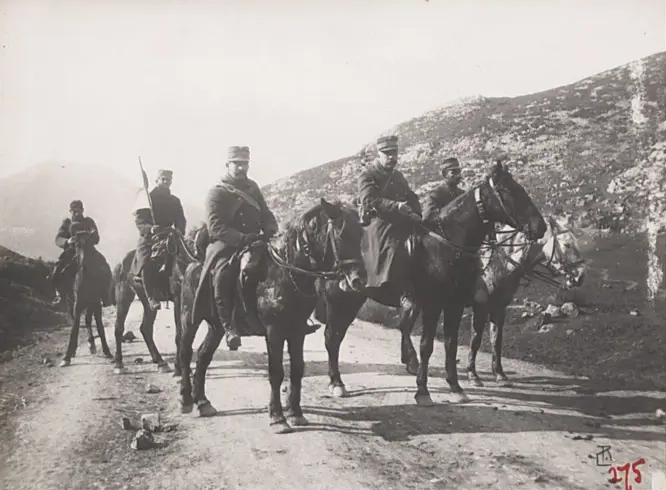

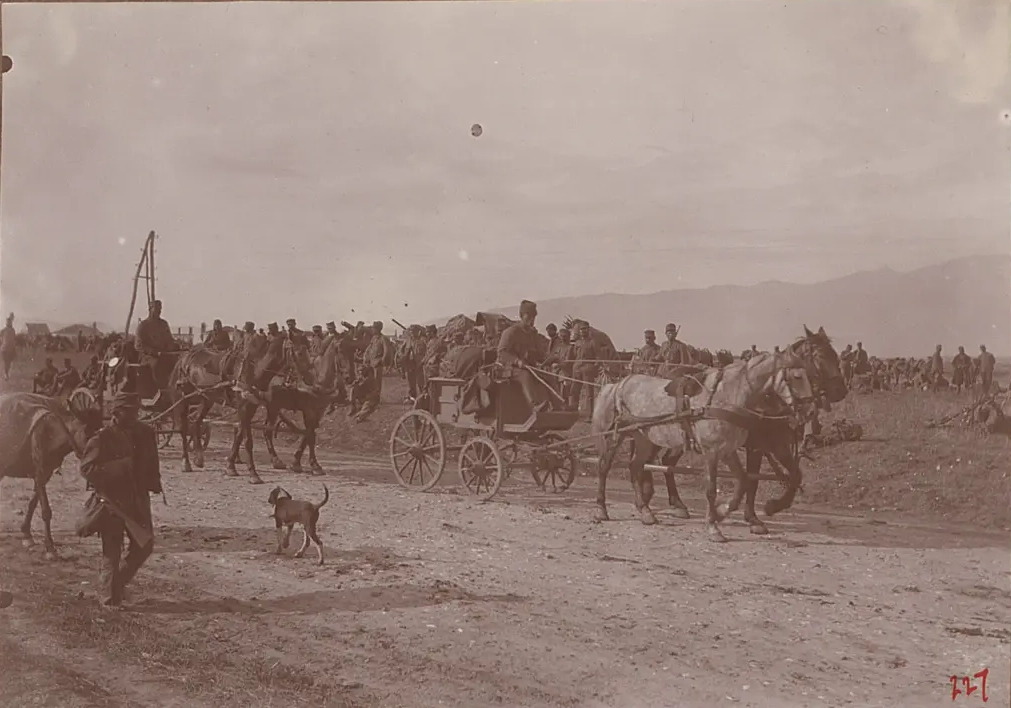

On March 15, 1897, Crown Prince Constantine, holding the rank of Commander-in-Chief, departed for the front in Thessaly. The incursion of armed men of the National Society into Macedonia provided the casus belli, and on April 5 the Ottoman Empire officially broke off relations with the Greek Kingdom. The war had begun.

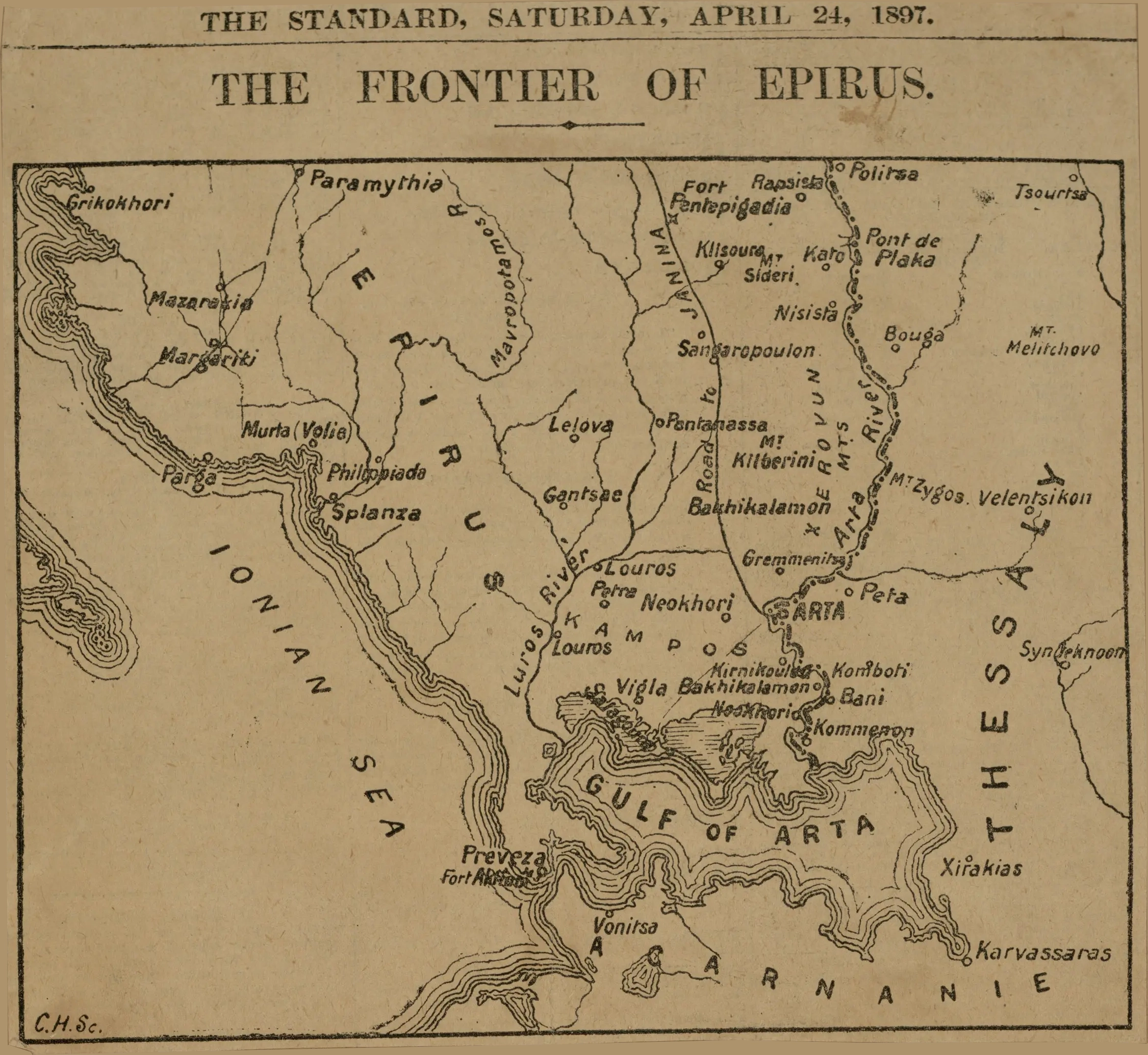

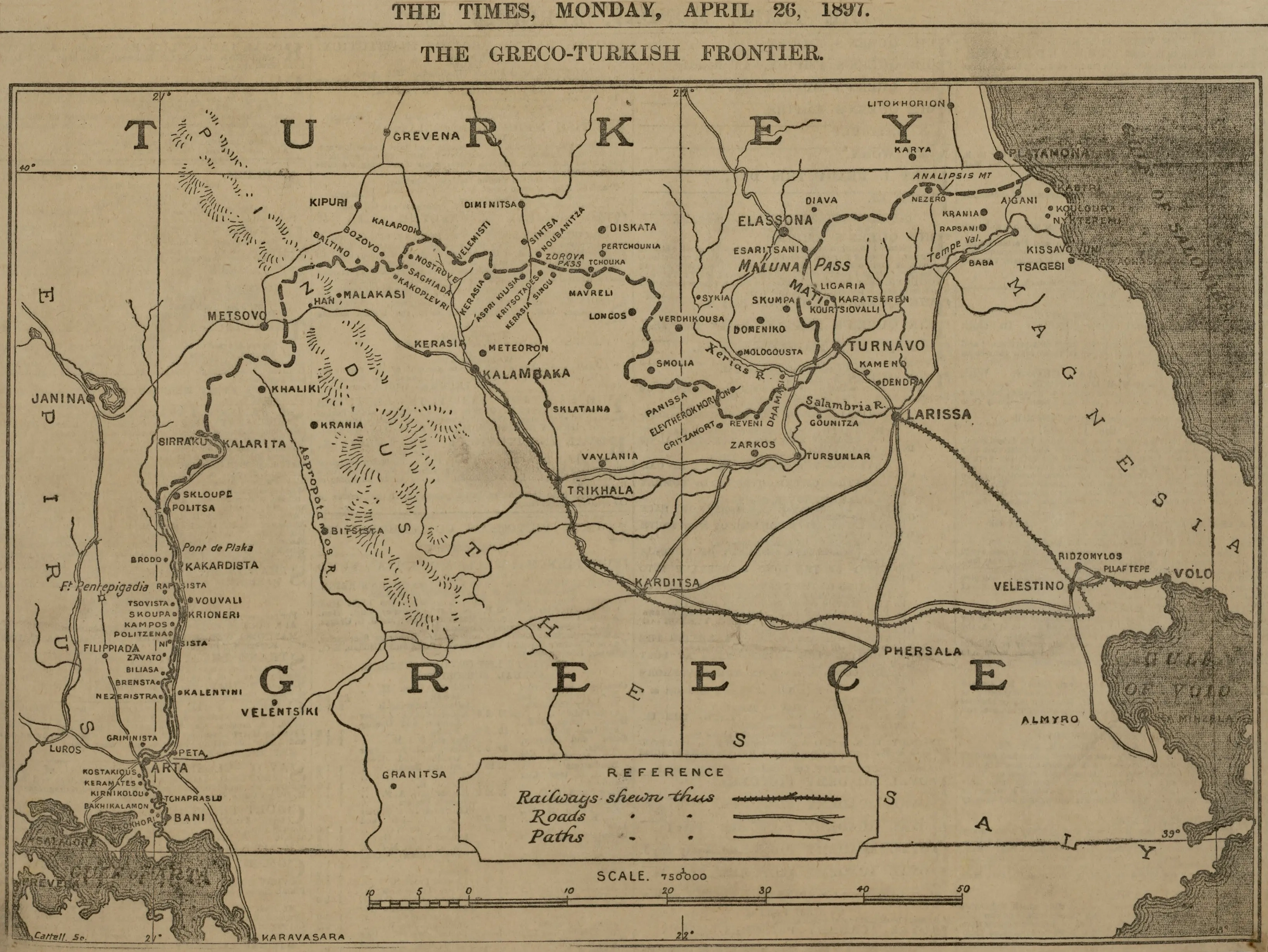

The configuration of Greece’s northern border with the Ottoman Empire dictated the existence of two different and independent theatres of war, Epirus and Thessaly, the latter being the more important, as the greater part of the Greek forces were concentrated there. Two Greek divisions defended the Thessalian front: one at Larissa under the command of N. Makris, and one at Alifaka under Infantry Colonel G. Mavromichalis. Two divisions were also dispatched to the Epirote front under Artillery Colonel Thrasyvoulos Manos.

The Ottoman forces were commanded by Etem Pasha, with Sheftek Pasha as Chief of Staff. In the first phase of the war, known as the “border battle,” there were several days of sustained and coordinated clashes along the northern borders of Thessaly at the three passes leading to Macedonia—those of Nezeros, Melouna, and Reveni. The Greek forces held their positions until April 12, 1897, when, after the battle of Deleria, a general retreat began from Tyrnavos to Larissa.

As Greek civilians and soldiers fled, the Ottomans occupied Tyrnavos (April 12, 1897) and Larissa (April 13, 1897), while the battle at Velestino lasted for ten days thanks to the vigor of General Smolensky’s brigade (April 14–24). The occupation of Volos (April 26, 1897) and the battle at Domokos in 1897 definitively determined the outcome of the war in favor of the Ottoman Empire. The armistice was signed outside Lamia on May 7, 1897, while a peace treaty was signed in Constantinople on November 22. According to its terms, Greece was obliged to pay a large war indemnity to the Empire and to cede a small part of Thessaly.

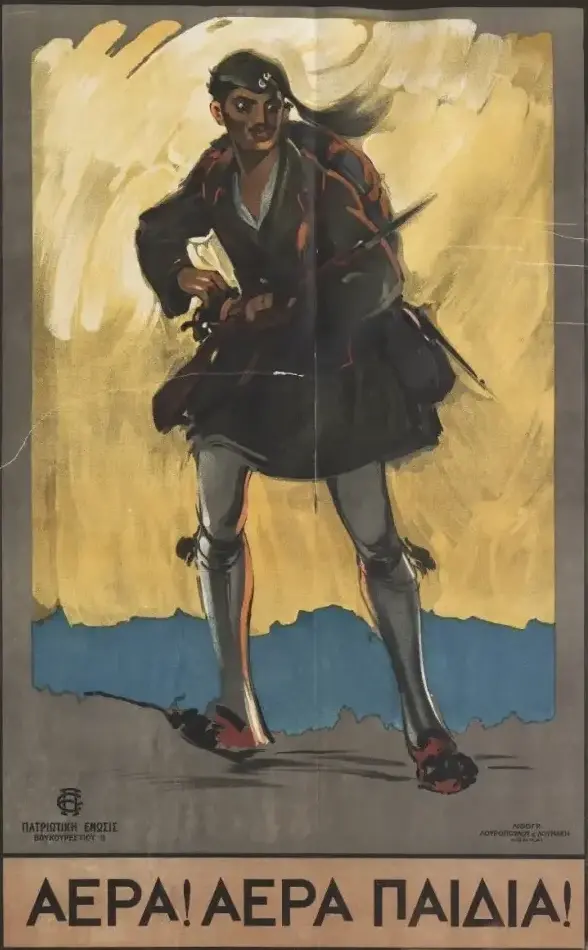

The Balkan Wars (1912-1913)

By the early 20th century, Greece, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Serbia had gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, though significant portions of their national populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912, the four states formed the Balkan League and declared war on the Empire on October 8. The First Balkan War ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London, on May 30, 1913.

Just weeks later, on June 16, 1913, the Second Balkan War erupted. Bulgaria, dissatisfied with the division of Macedonia—secretly settled between its former allies, Serbia and Greece—launched an attack against them. Defeated decisively, Bulgaria lost most of its gains from the First Balkan War under the Treaty of Bucharest and was also forced to cede the southern third of Dobruja to Romania.

The Balkan Wars stripped the Ottoman Empire of most of its European territories and marked one of the greatest national catastrophes in its history. At the same time, Austria-Hungary emerged weakened, confronted by a larger and more powerful Serbia.

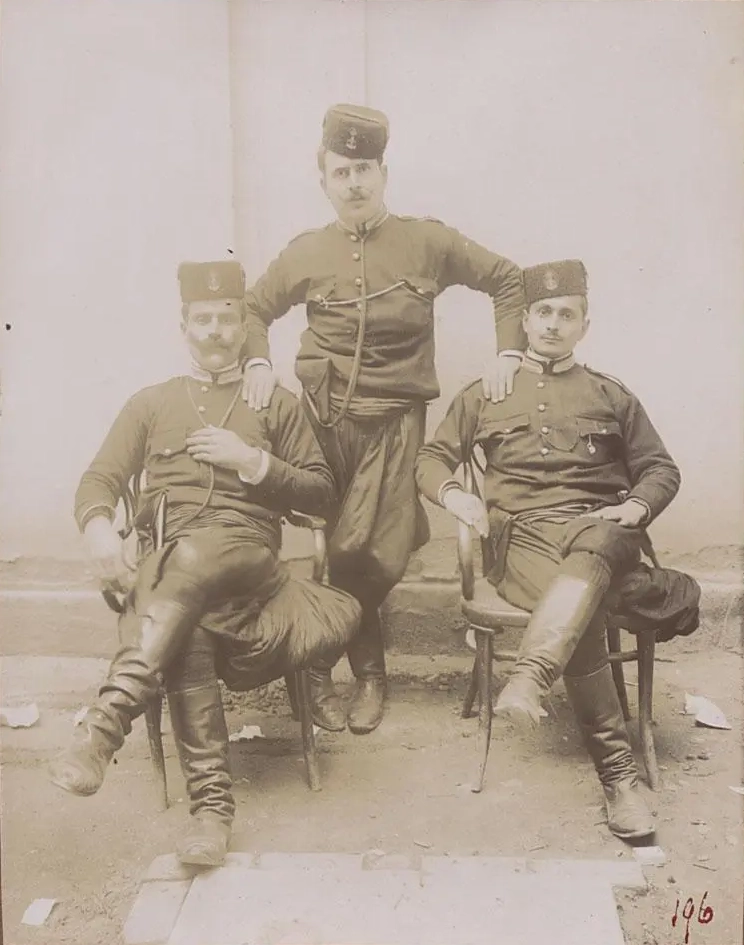

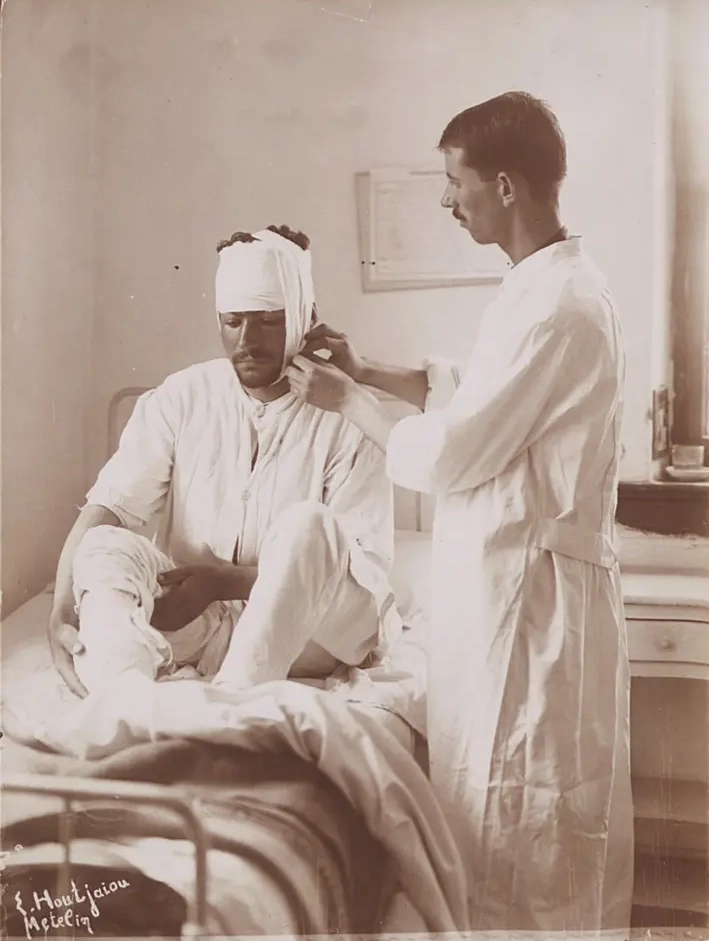

The Gennadius scrapbooks on the Balkan Wars are of particular interest as they contain photographs of leading photographers of the era. The Romaidis brothers, renowned in Athens since the mid-19th century, documented key moments during the wars. Aristotelis Romaidis captured vivd scenes of battle, many reproduced as postcards. He worked alongside Zeitz, who accompanied Crown Prince Constantine, the Commander-in-Chief, on campaigns in Epirus and Macedonia.

Another prominent Greek photographer, Anastasios Gaziades, began his career before 1880 and continued into the early 20th century, when his sons took over. Ships were among his favorite subjects. His studio, listed in period sources as: A. Gaziades, ATHENES – PIREE, Rue Stade – Eole, was well known at the time.

Simos Houtzaios, born in 1873 in Agiasos on Lesvos, learned photography in Alexandria from his uncle, the painter Kalpaxidis. He traveled across Europe until 1899, then returned to Mytilene to work with the Czechoslovak photographer Fritz J. Mraz in his studio on Mitropoleos Street. Later, he opened his own studio on Vernardaki Street. In 1913, he published a photographic album entitled “The Occupation of Mytilene by the Greek Army”.

The Paris Exposition Universelle (1889)

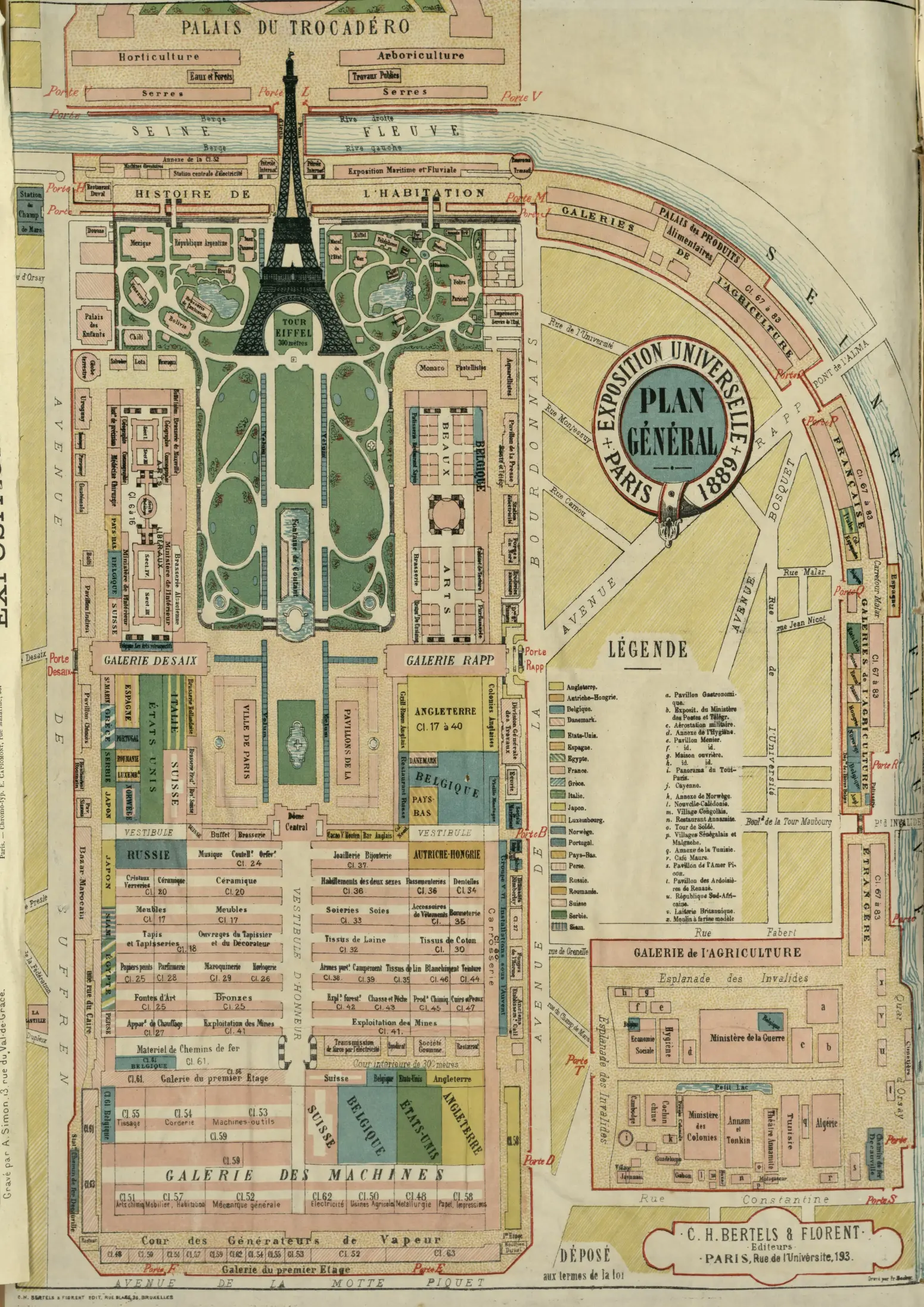

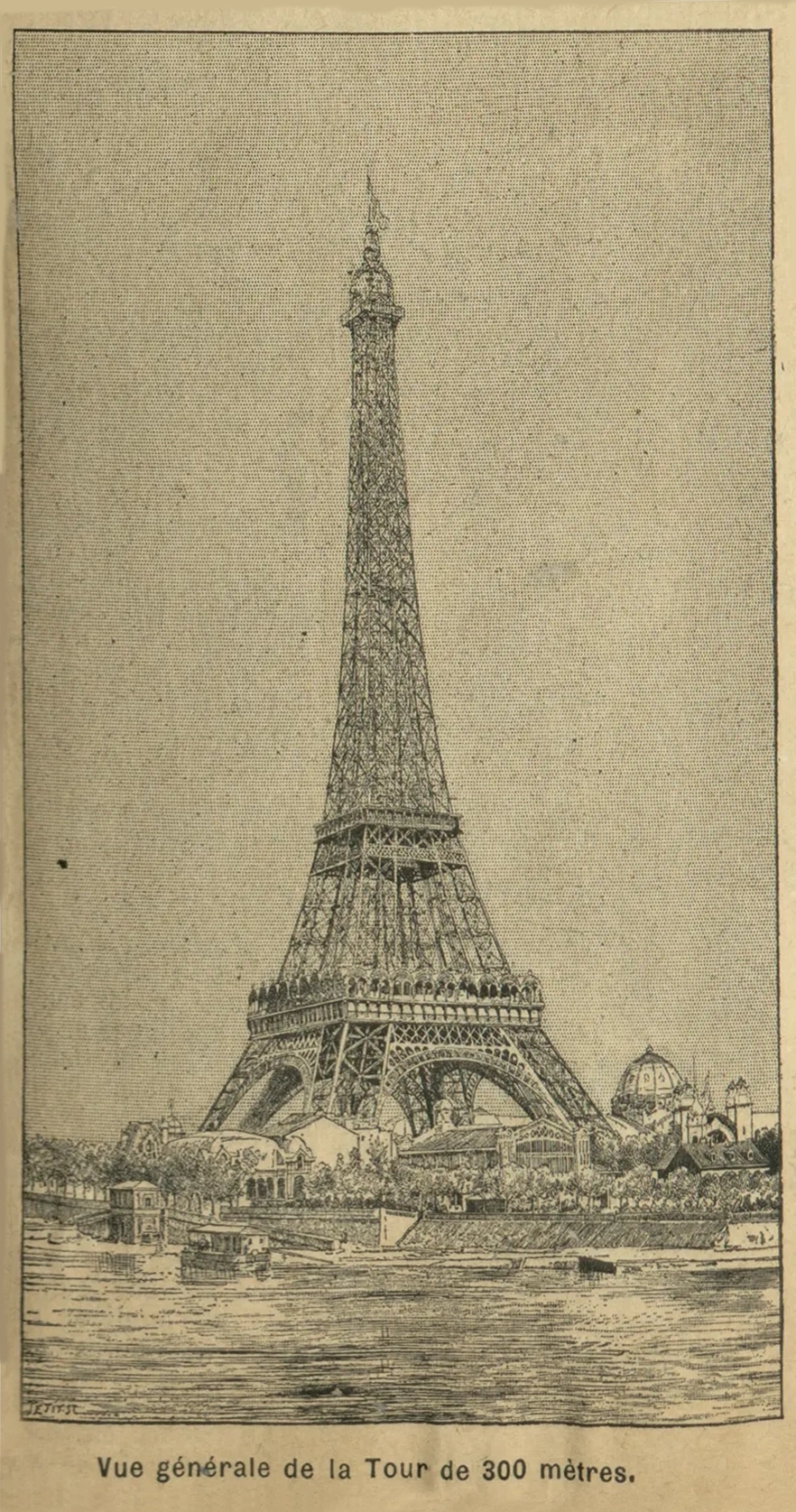

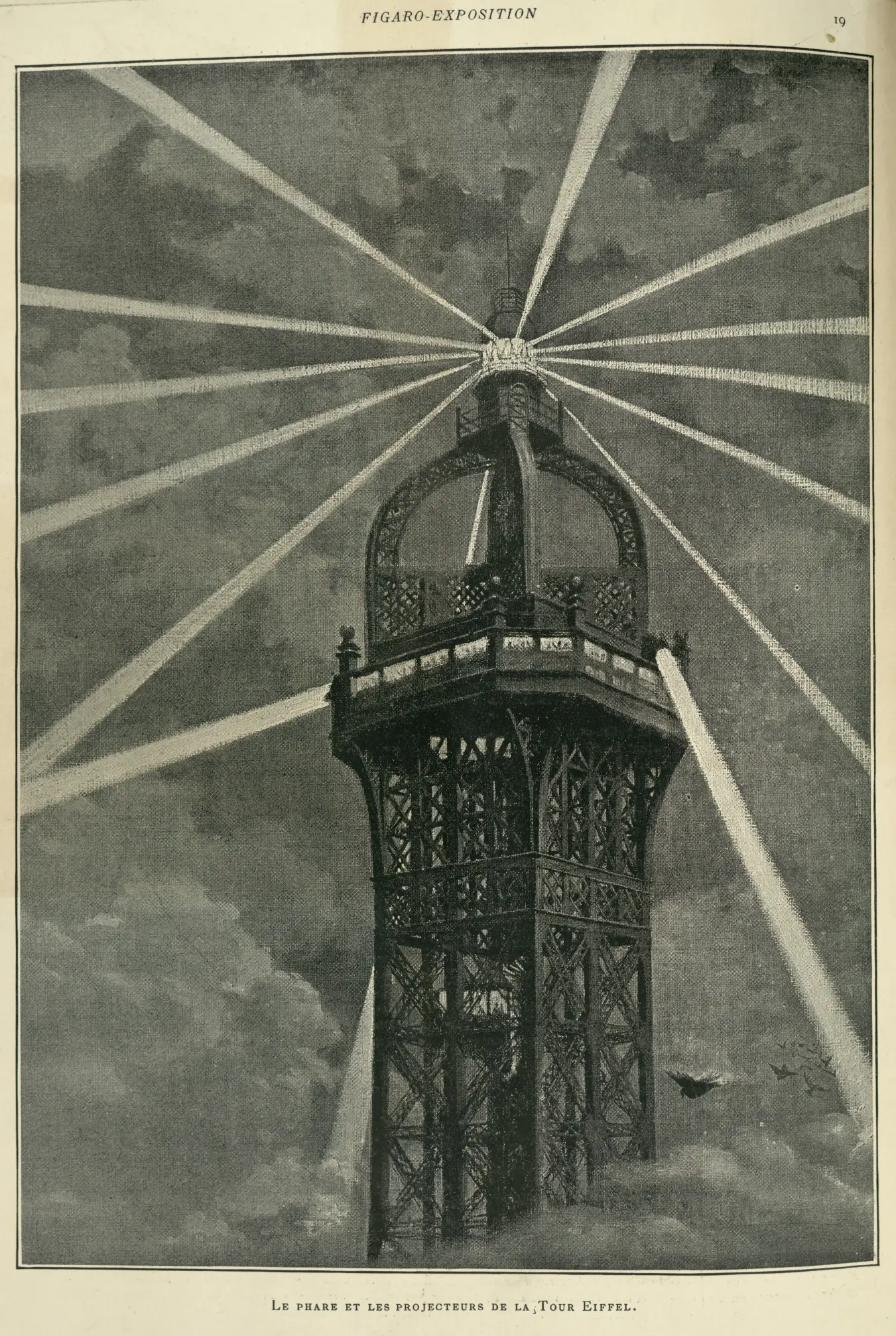

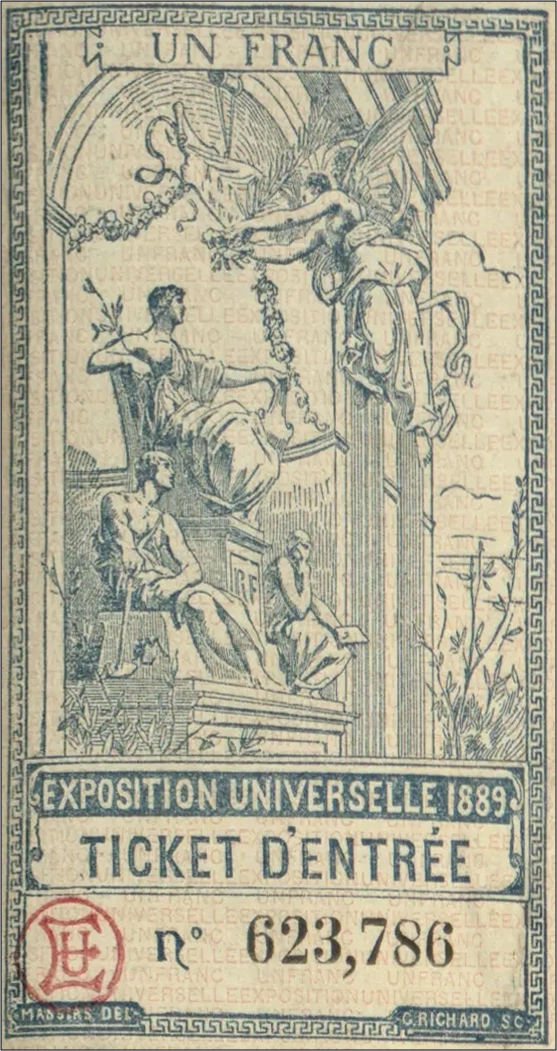

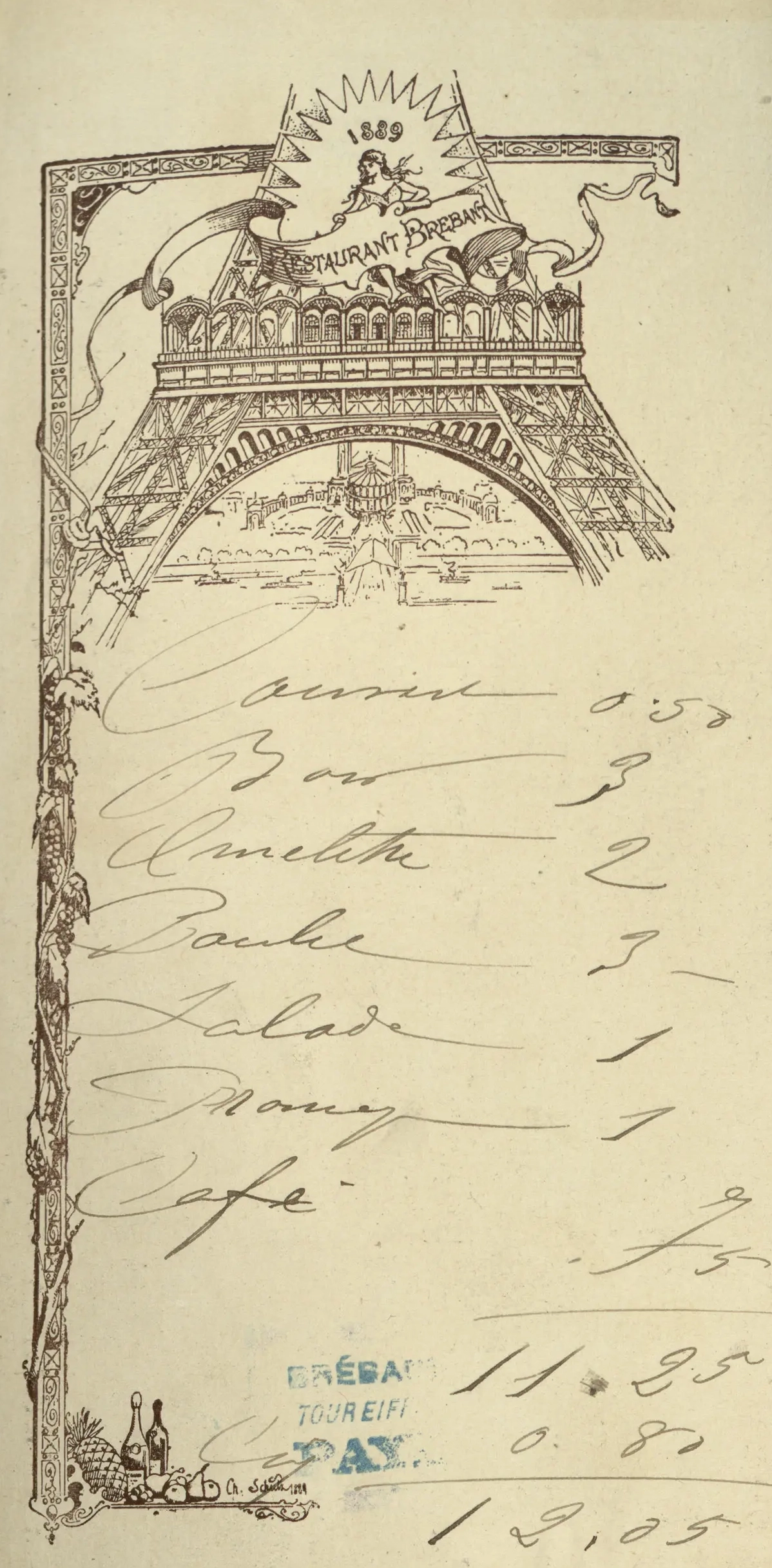

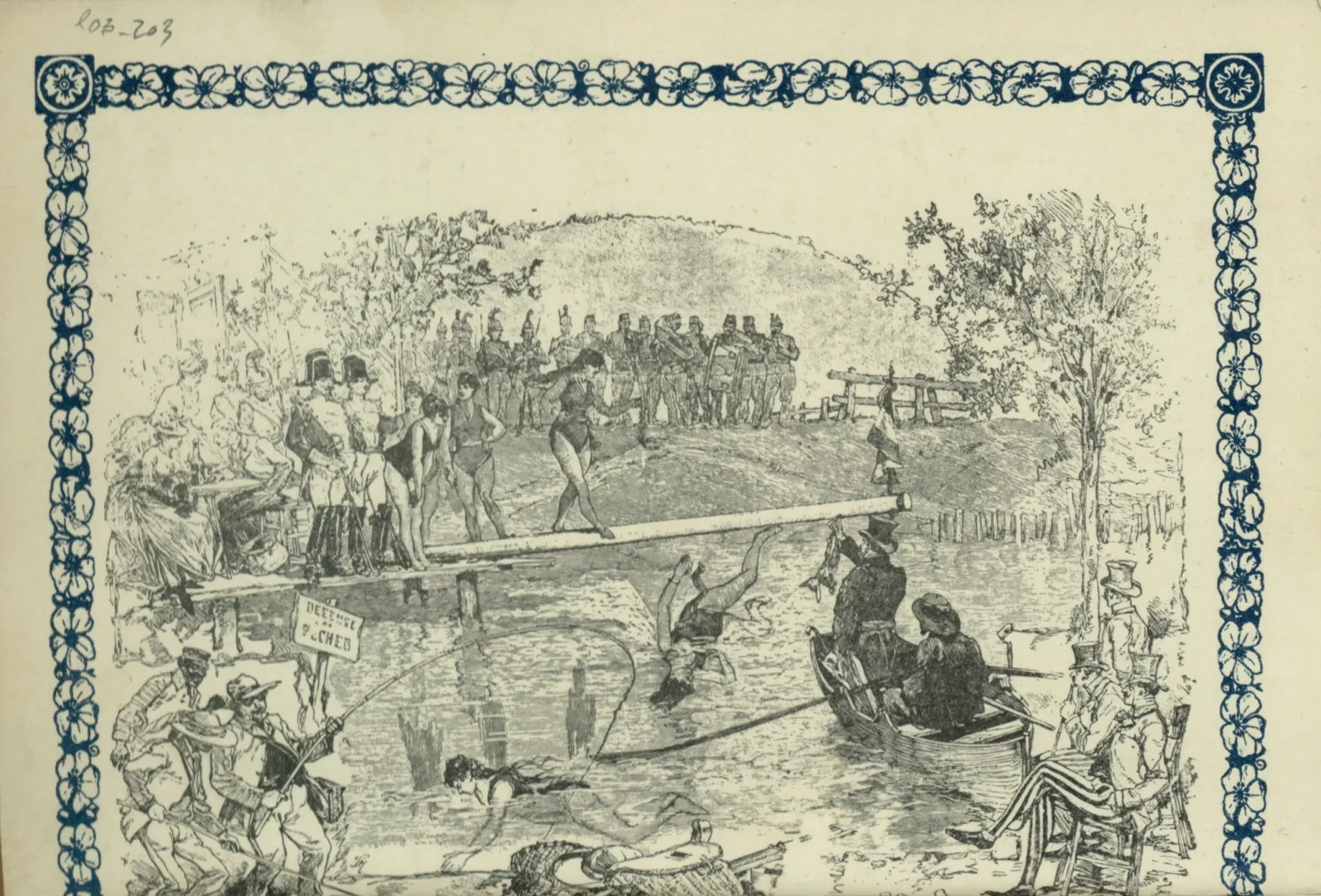

The scrapbooks of Joannes Gennadius include fascinating material from his travels in Europe and America, capturing the spirit of the times. The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889 (May 6 – October 31), which Gennadius attended, drew more than thirty-two million visitors. Marking the centenary of the French Revolution, the Exposition sought to stimulate France’s economy and overcome the economic downturn by celebrating science, technology, and the arts. One of the world’s most iconic structures, the Eiffel Tower, was constructed for the 1889 Exposition. At 324 meters tall, it remained the tallest building in the world for 41 years.

Admission to the Exposition cost forty centimes at a time when a “cheap” plate of meat and vegetables in a Paris café cost ten. Visitors paid considerably more to see the most popular attractions of the exhibition: climbing the Eiffel Tower cost five francs, while entry to panoramas, theaters, and concerts cost one franc.

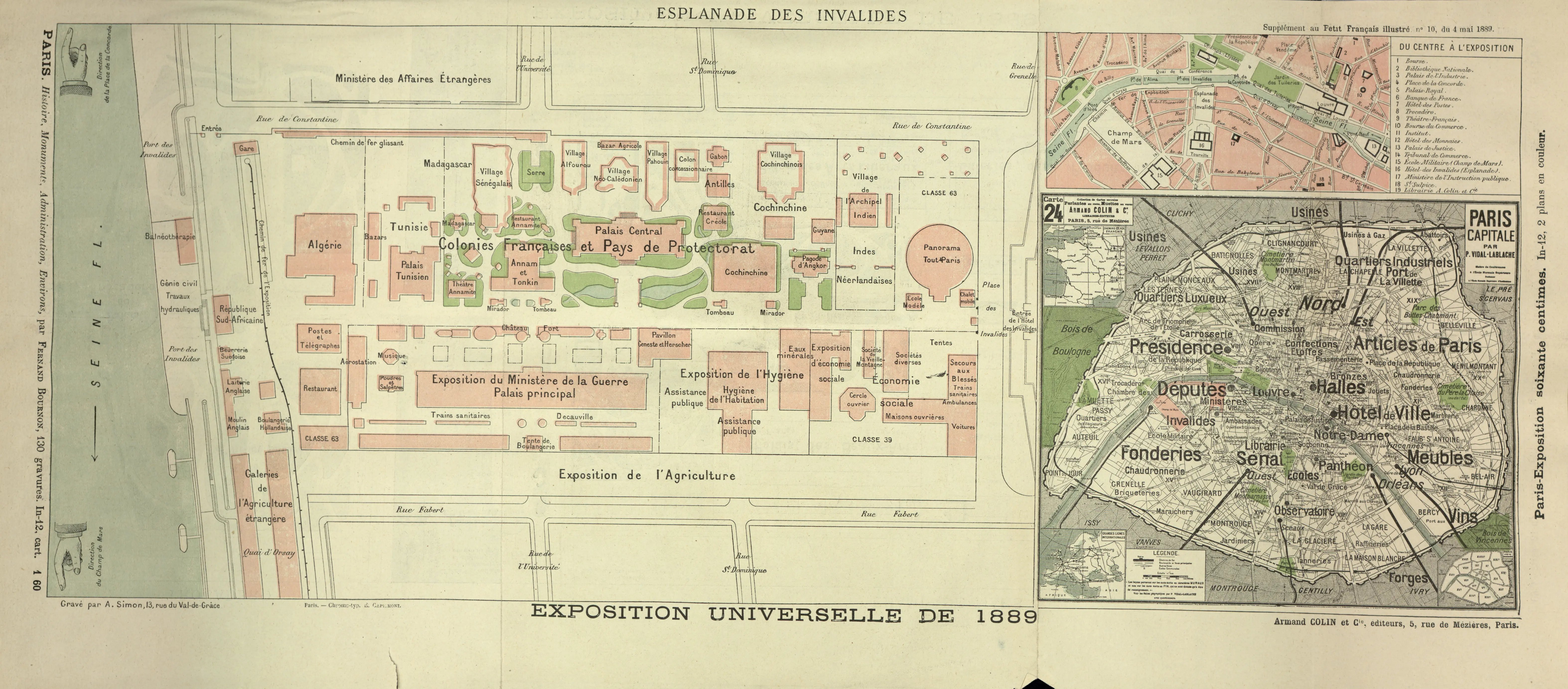

The Exposition was spread over two main sites.

The principal grounds were the Champ de Mars, on the left bank of the Seine, where the Eiffel Tower was built. On the right bank, from the Trocadéro Palace (originally built for the 1878 Exposition) down to the river, organizers created parks, gardens, and fountains.

A smaller site at Les Invalides showcased the pavilions of the French colonies. Numerous outdoor cafés and restaurants offered food from Indochina, North Africa, and other cuisines from around the world. Yet the colonial exhibition, which included displays of Indigenous peoples, also provoked criticism from the communities involved.

Transatlantic Voyage (1893-1894)

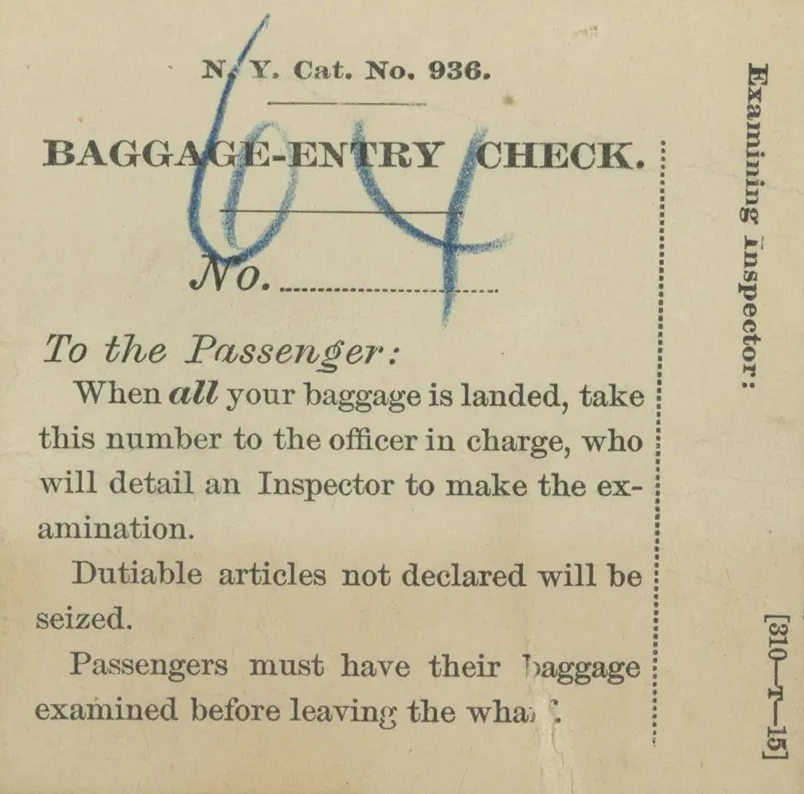

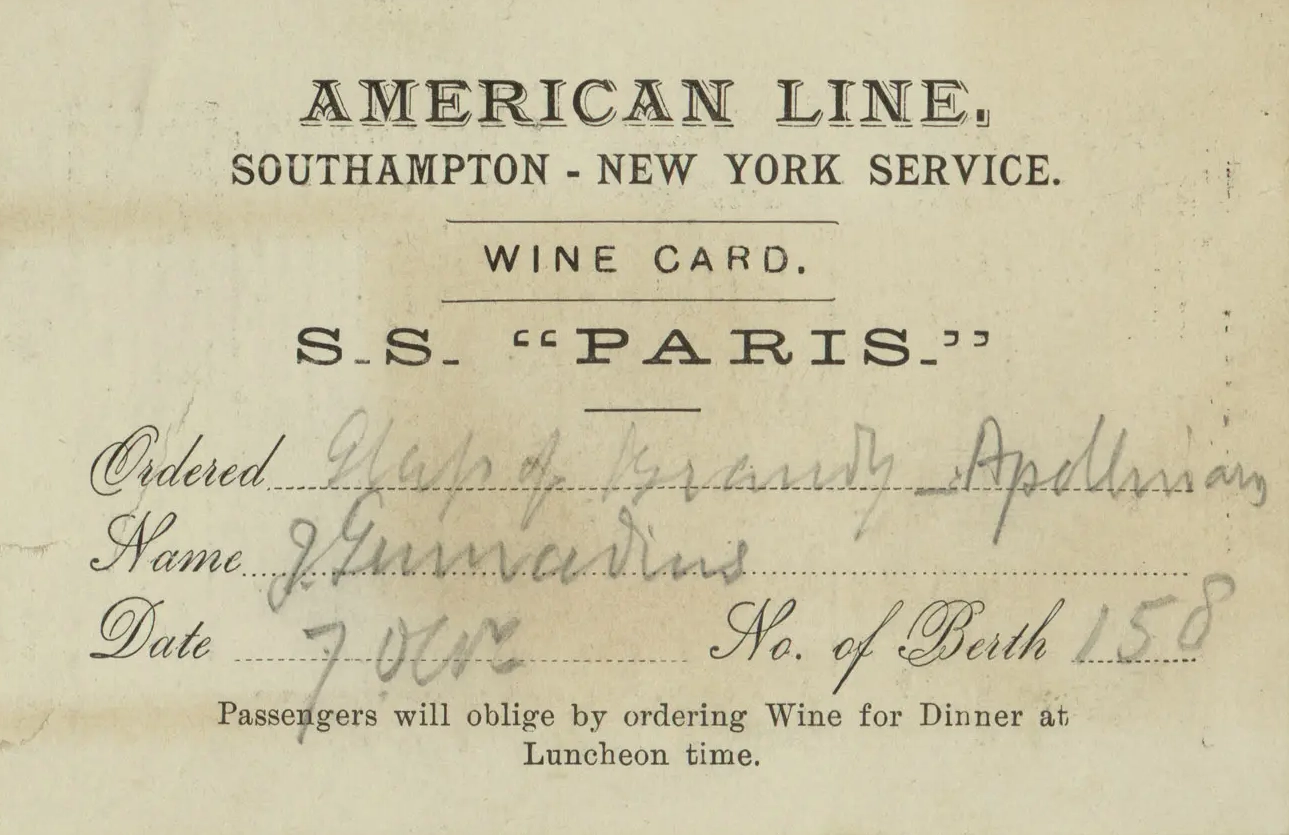

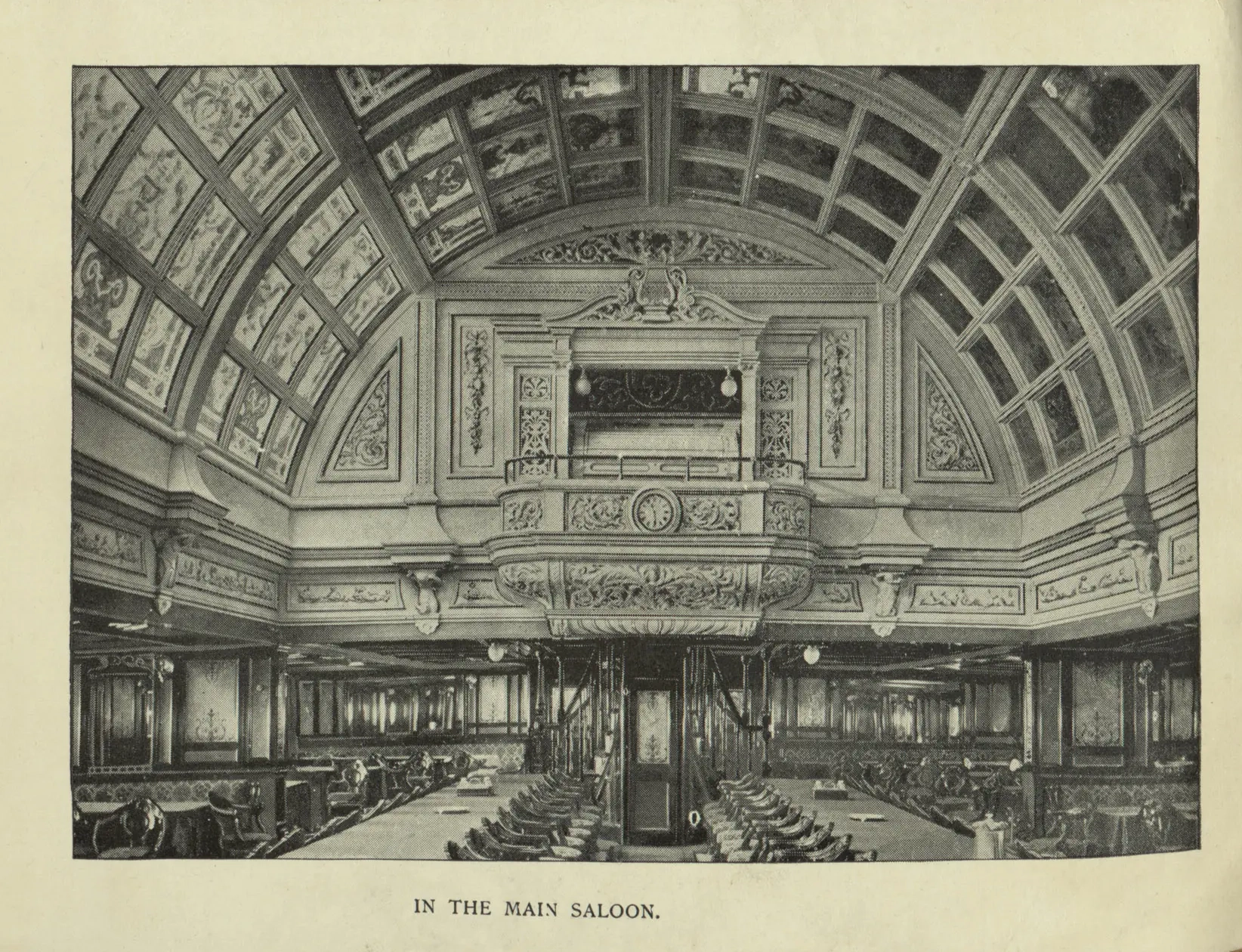

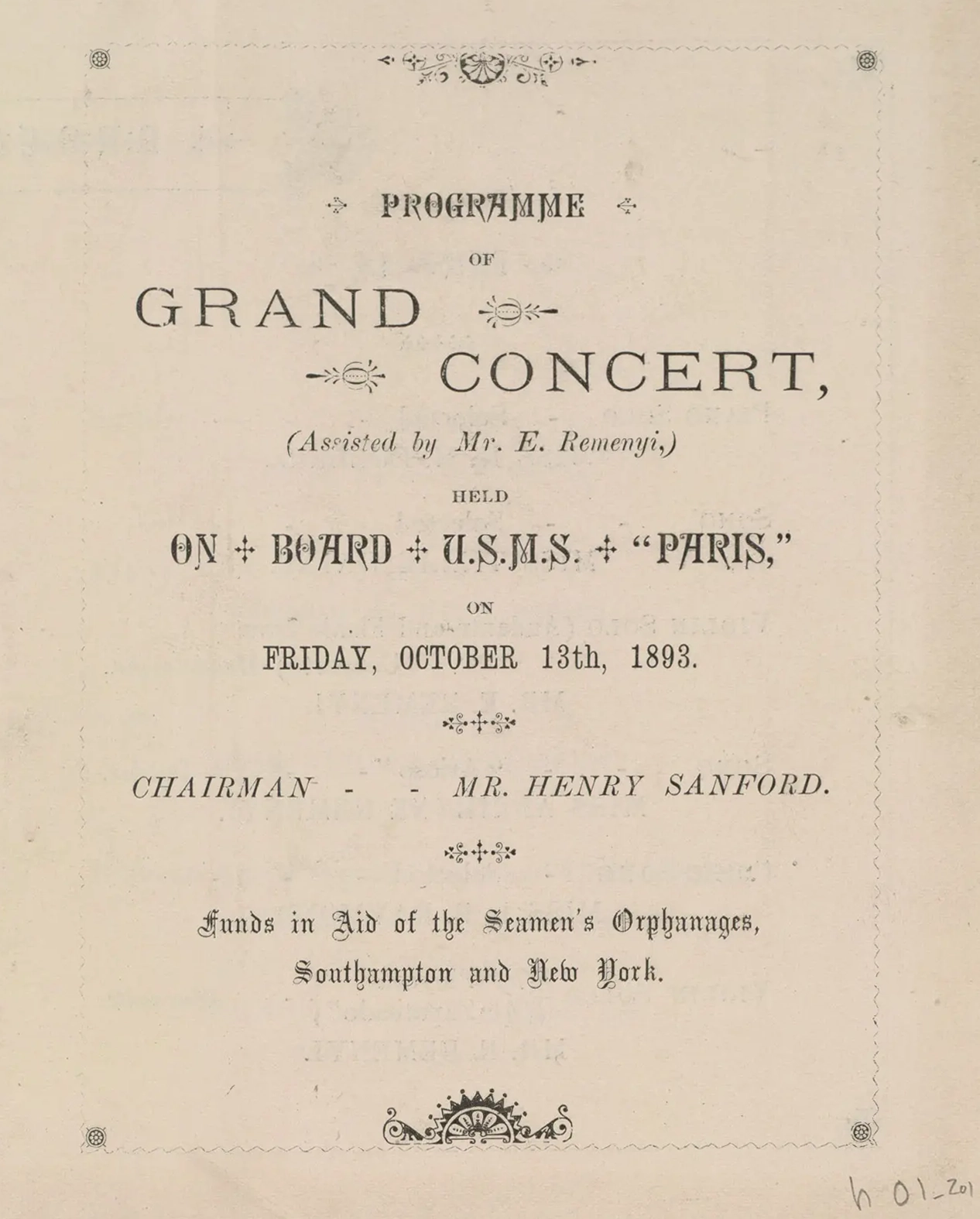

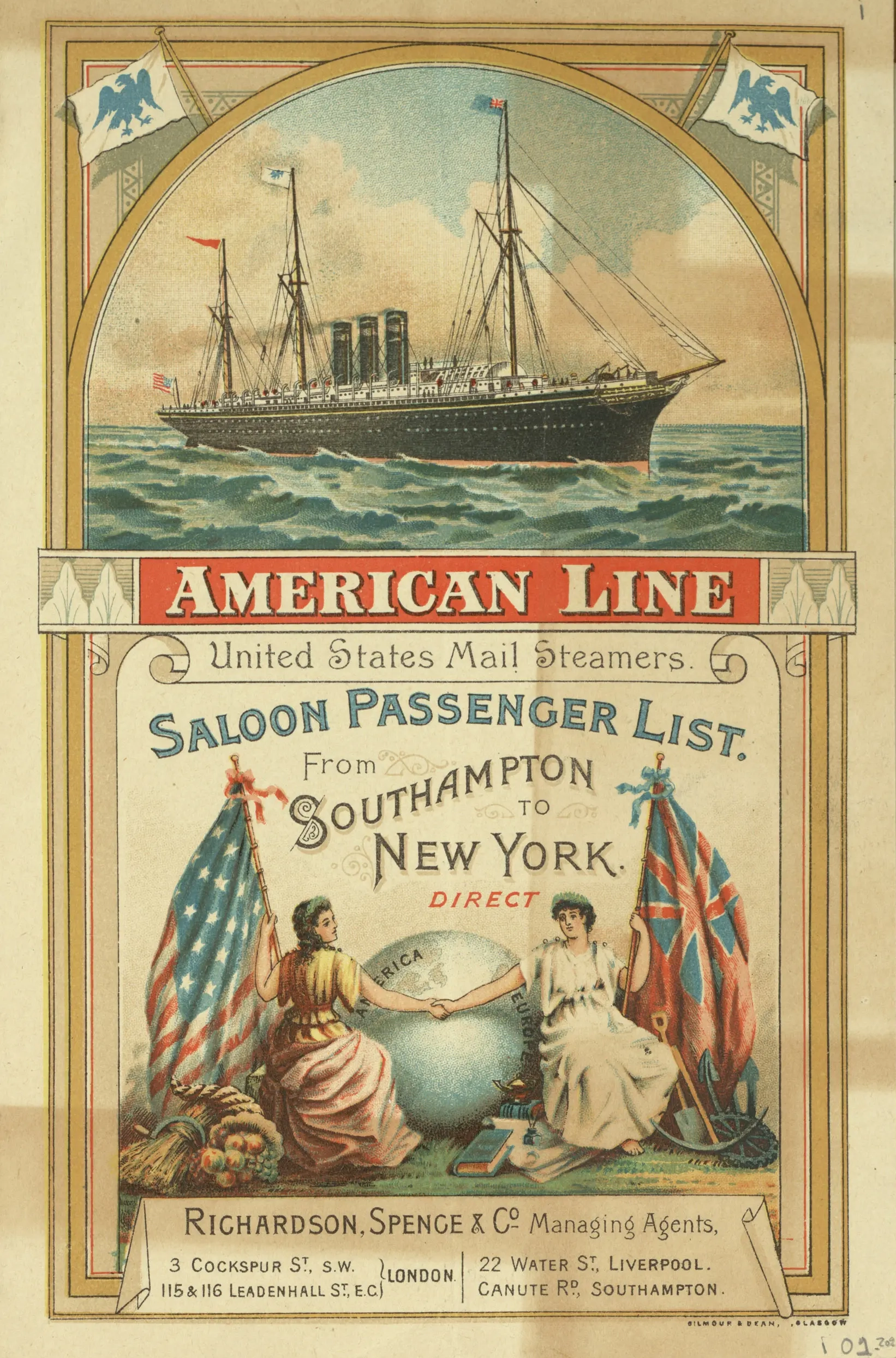

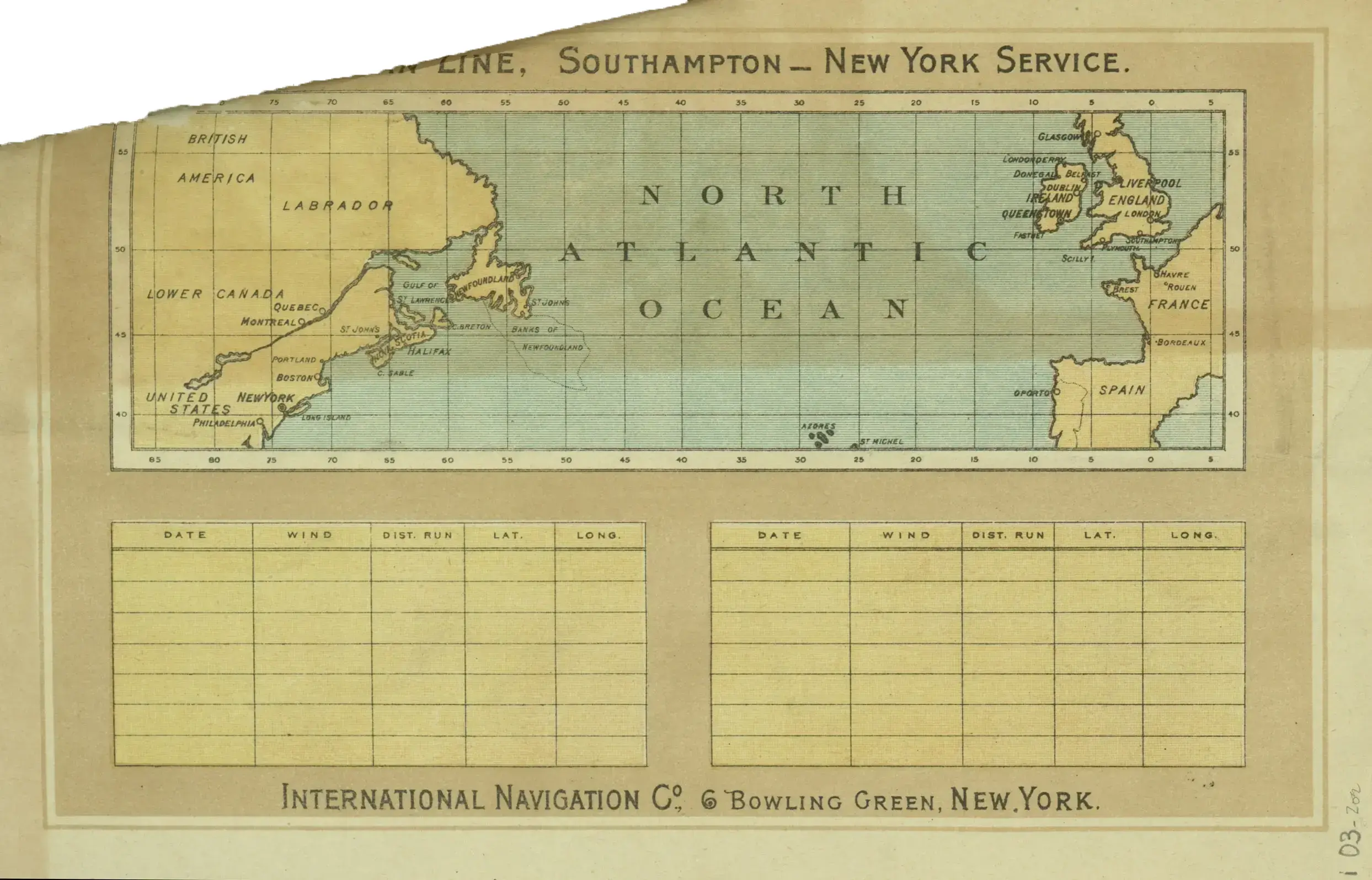

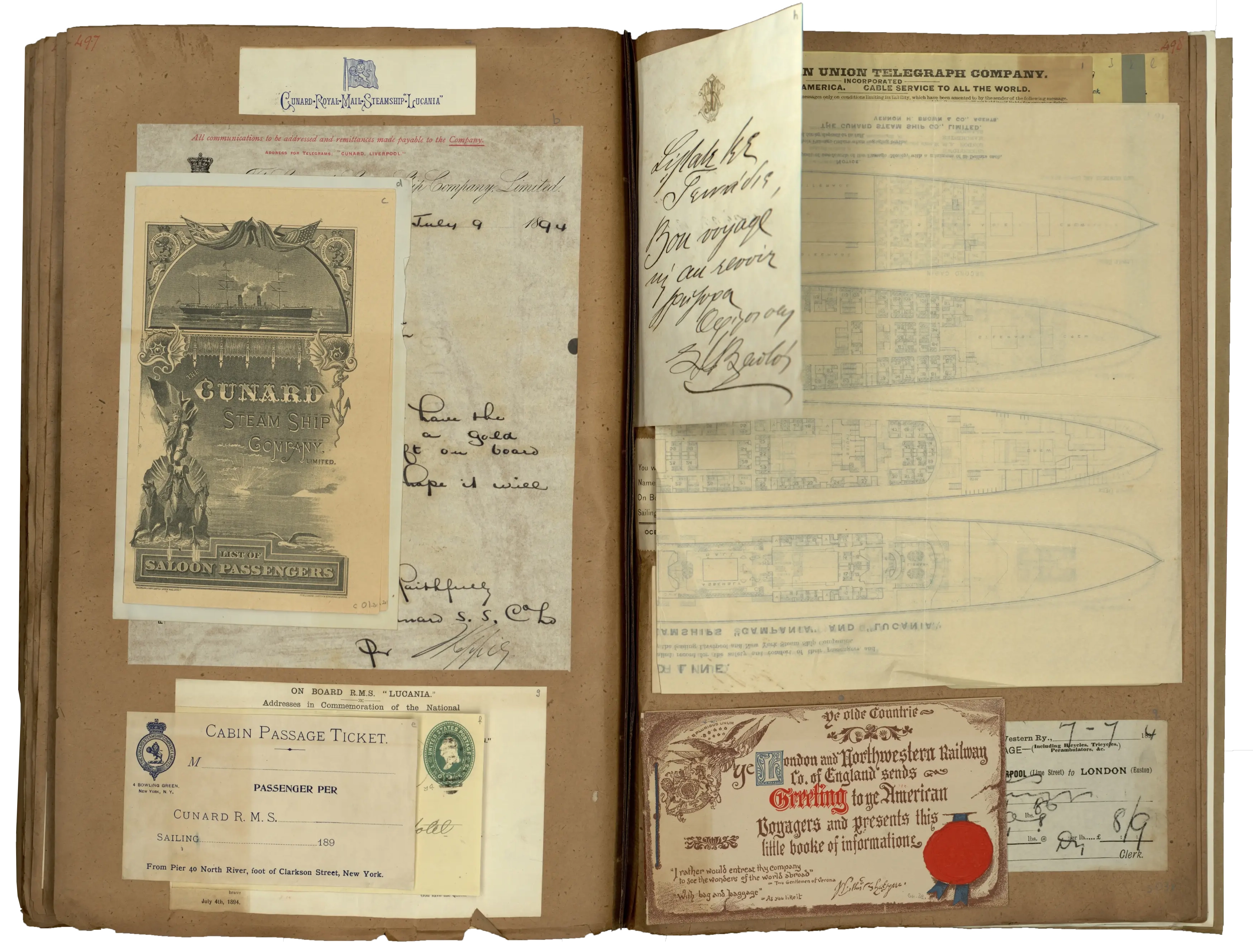

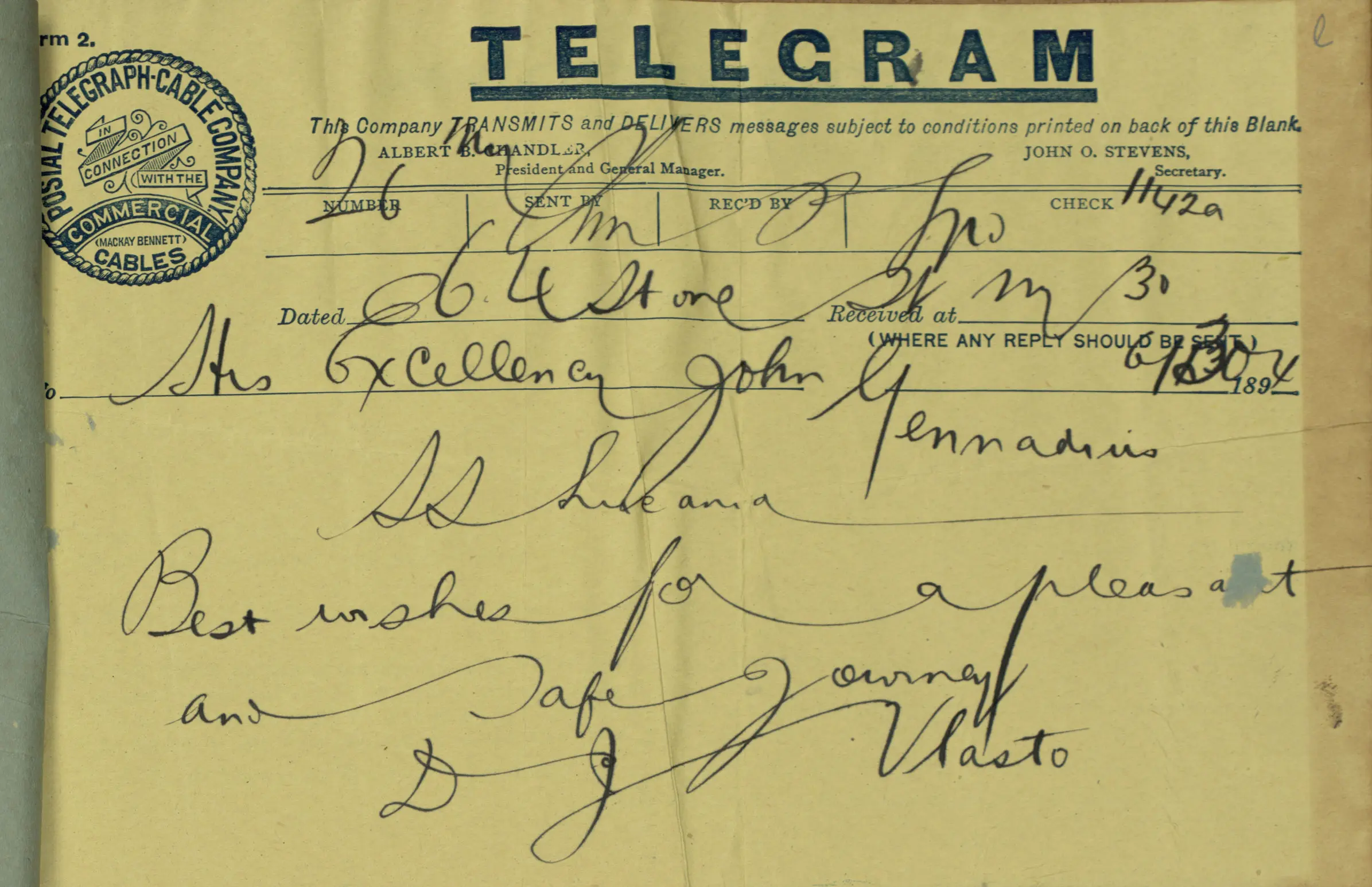

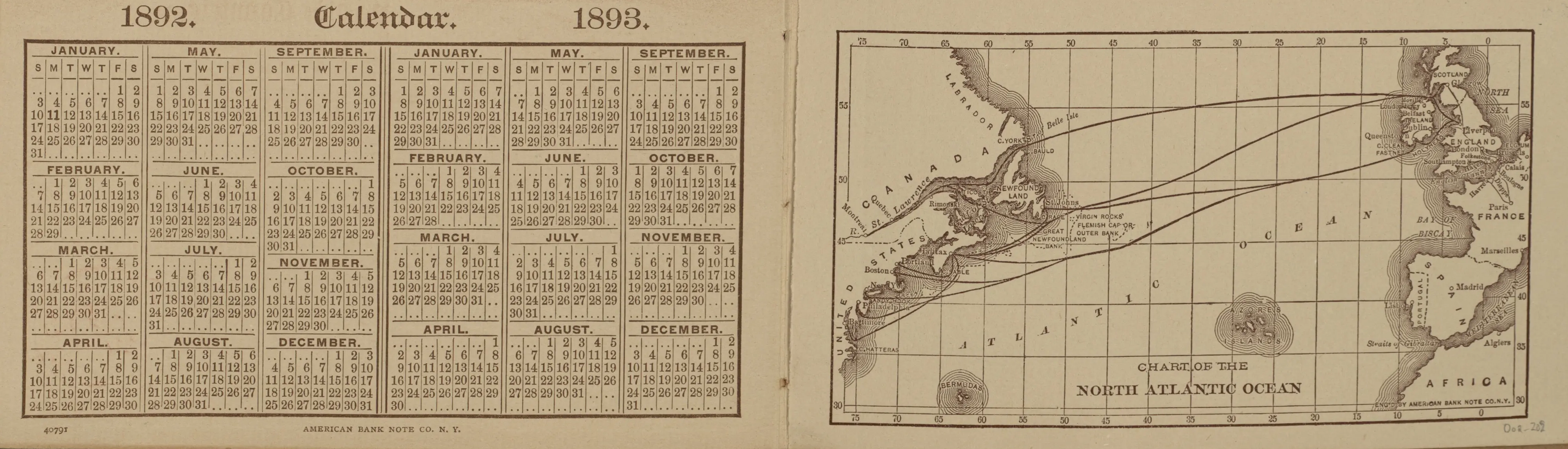

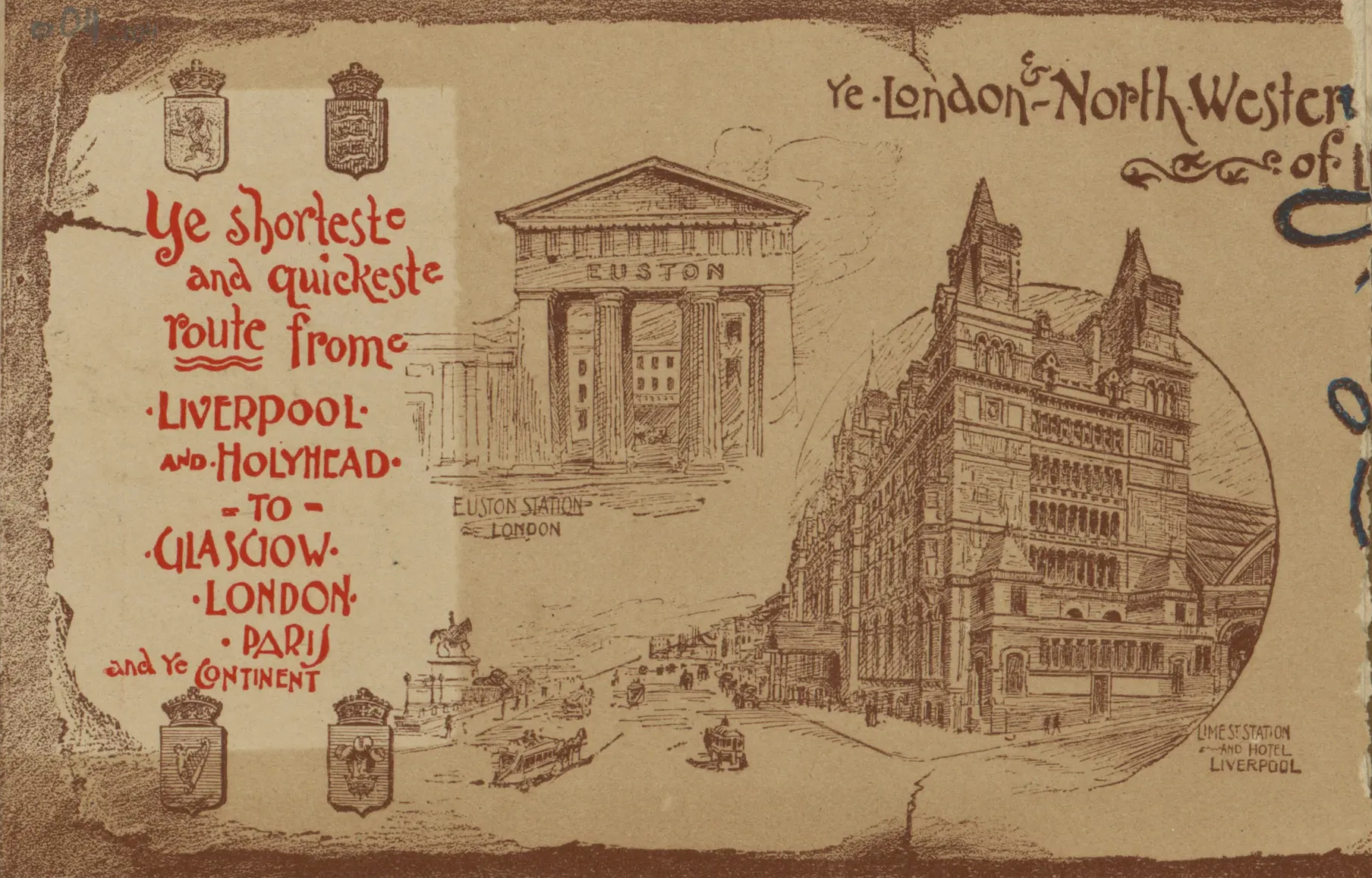

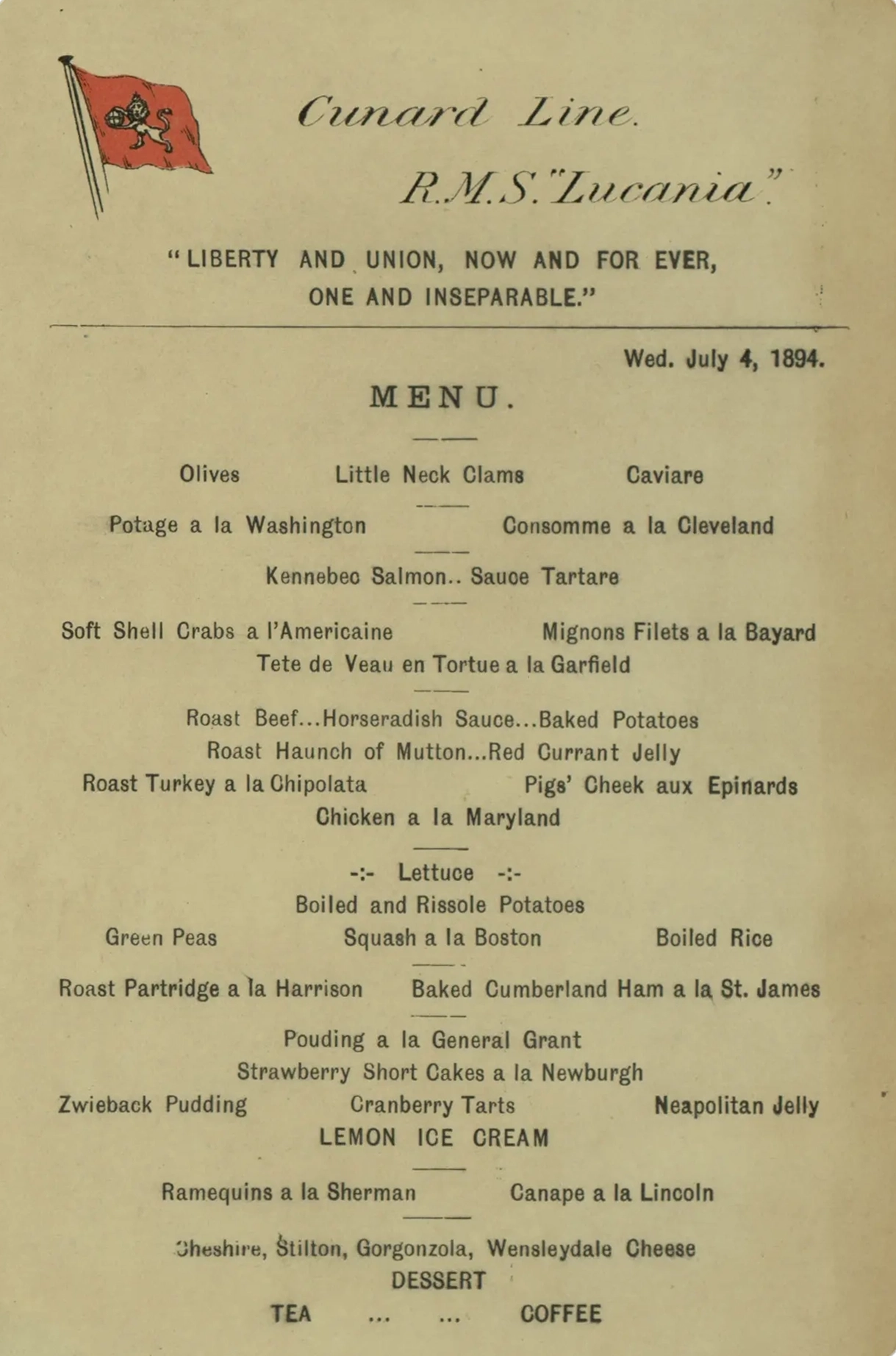

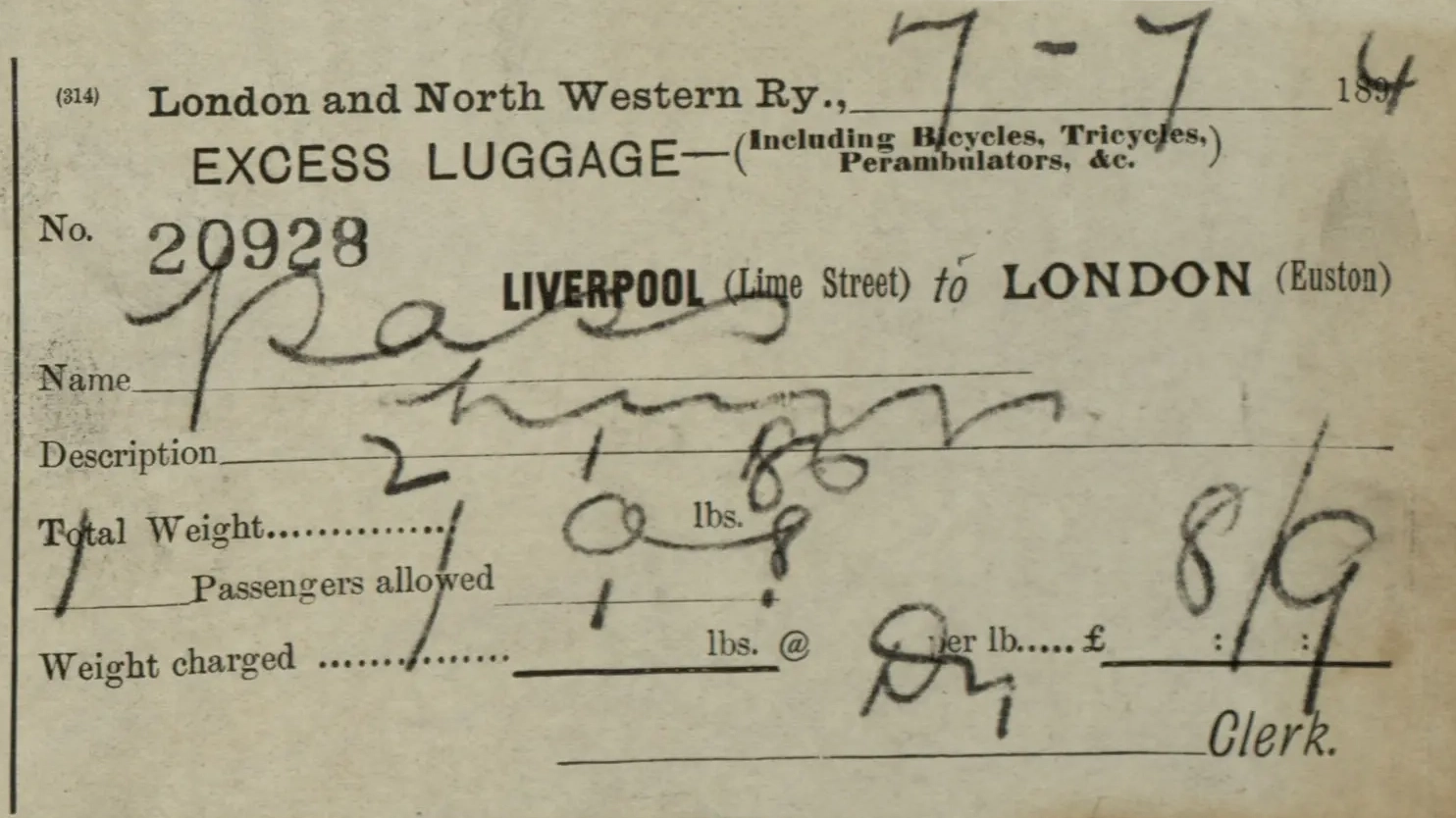

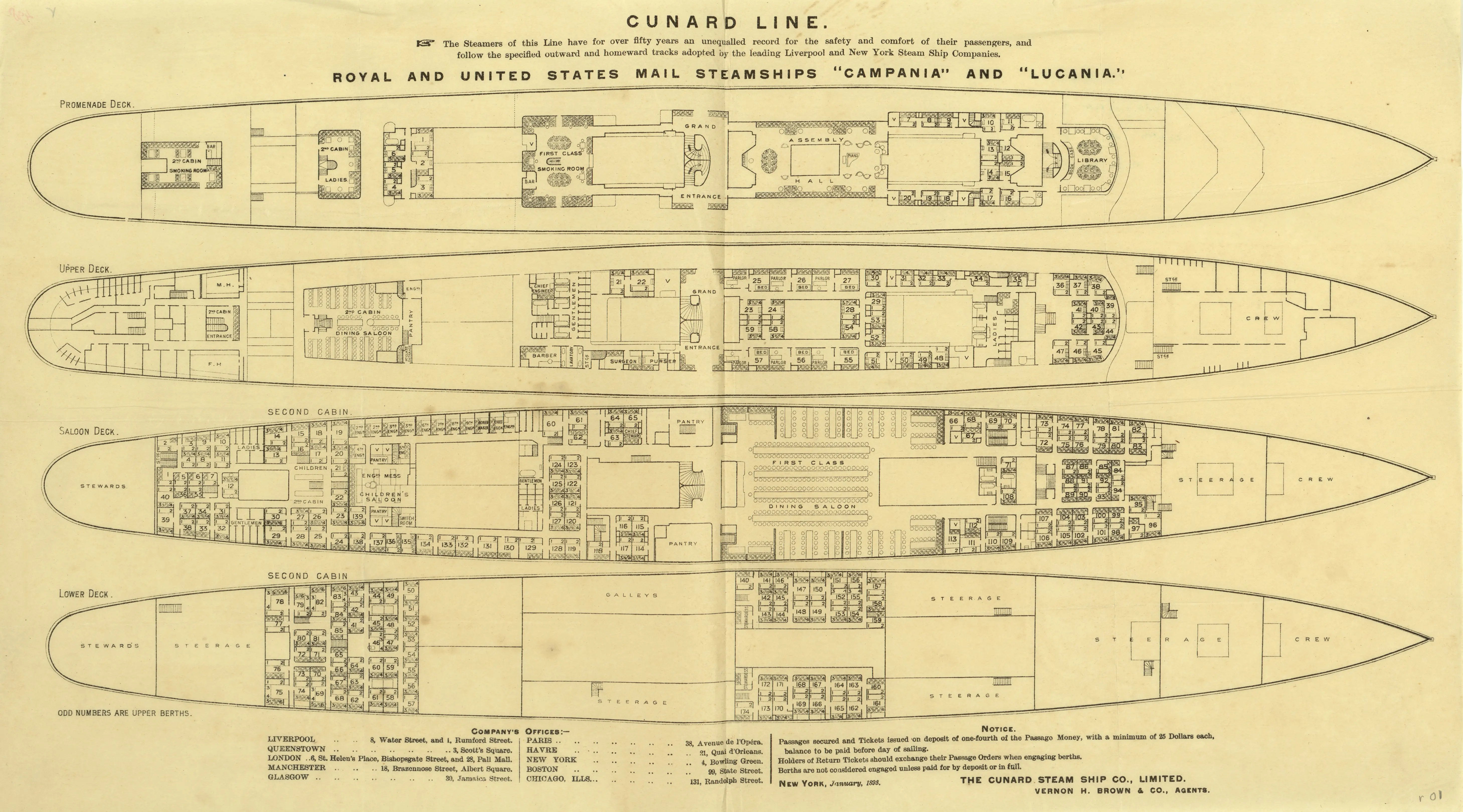

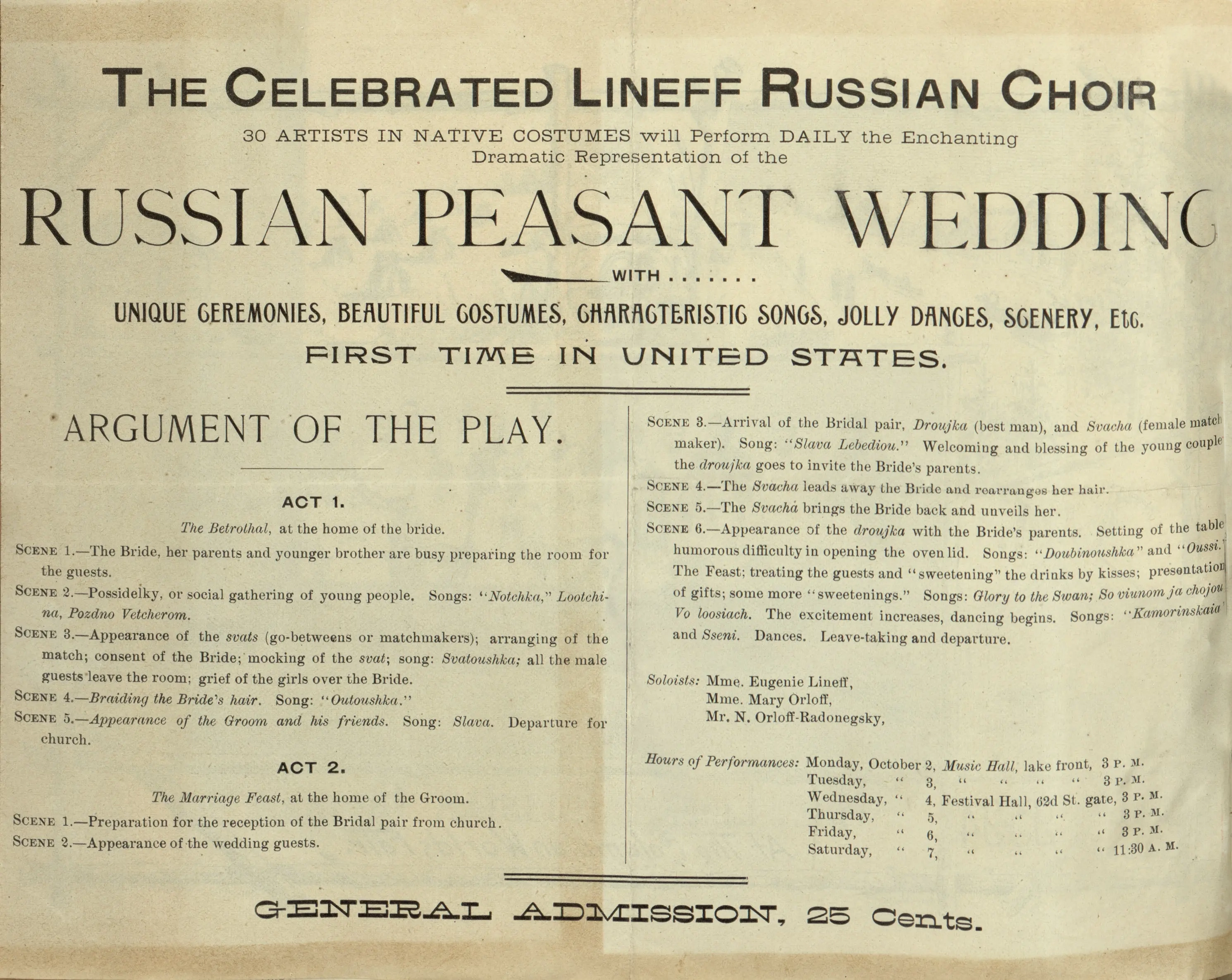

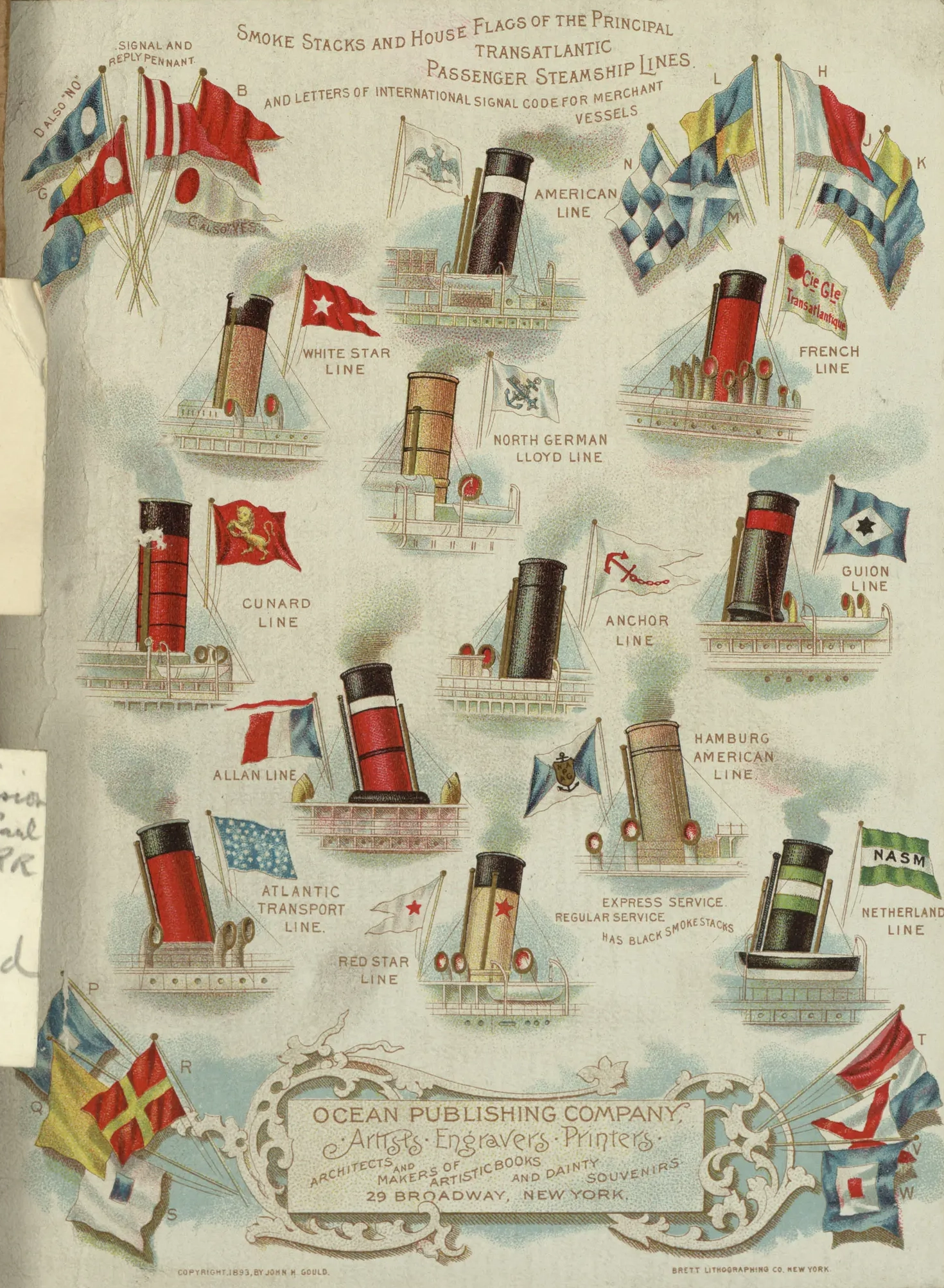

Joannes Gennadius traveled to the United States in October 1893, remaining there until June 1894. He left for New York from Southampton aboard the American Line’s SS Paris, and on his return, he sailed from New York to Liverpool on the Cunard liner Lucania. His scrapbook contains remarkable documents from this voyage.

The 19th-century advent of steamships revolutionized transatlantic passenger travel, making it faster, safer, and more reliable. The wooden SS Great Western, built in 1838, is widely regarded as the first true transatlantic liner, linking Bristol and New York. Designed by the British civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, it set the standard for a new generation of ocean liners.

In 1840, the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company launched the Liverpool–Halifax–Boston route, deploying four new Britannia-class steamships under a British government postal contract. The company later became the Cunard Line. To challenge Cunard’s dominance, the U.S. government awarded a postal contract in 1850 to the New York & Liverpool United States Mail Steamship Company—soon known as the Collins Line—whose four vessels were newer, larger, faster, and more luxurious than Cunard’s.

Rivalry—especially for the title of the fastest ship—soon developed among the industrial powers of the age: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and the United States. Building great ocean liners became not only a commercial enterprise but also a symbol of engineering prowess and national prestige.

Today, Cunard’s RMS Queen Mary 2 remains the only ocean liner to operate regular transatlantic crossings year-round, most often between Southampton and New York.

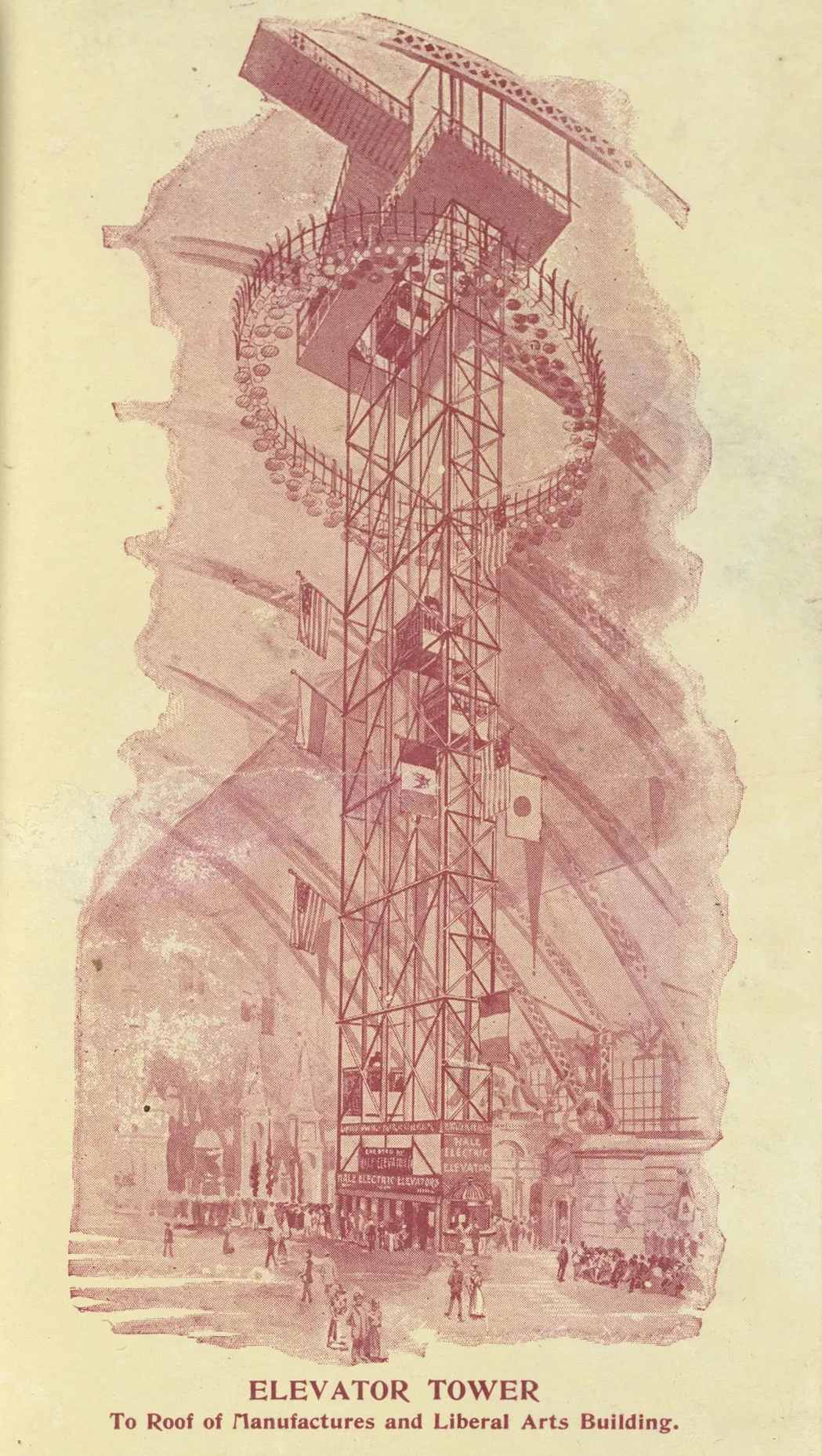

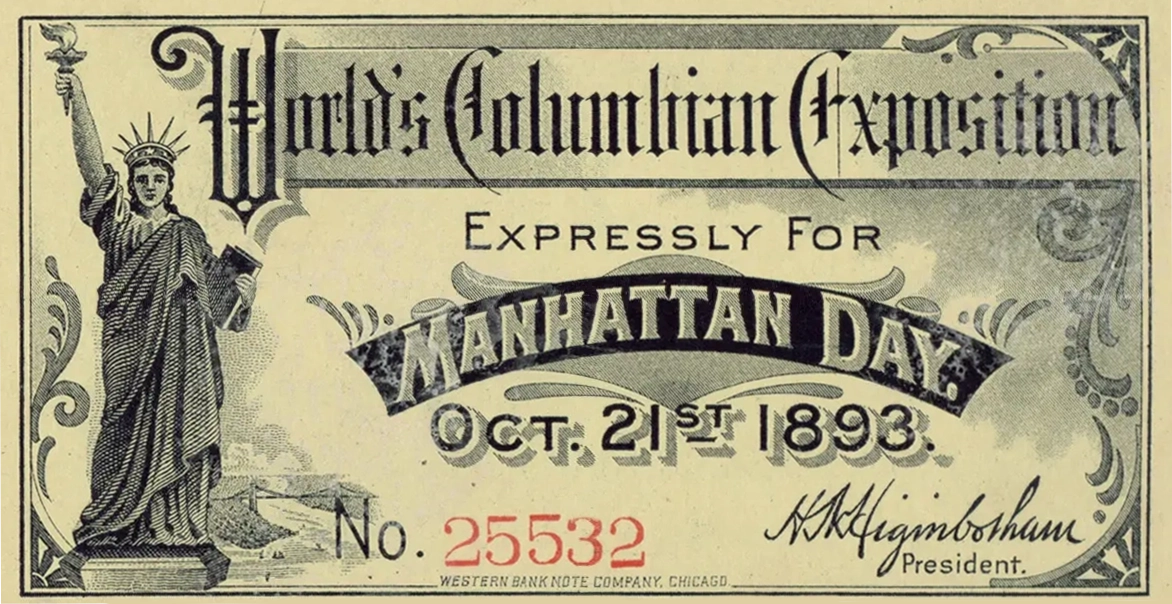

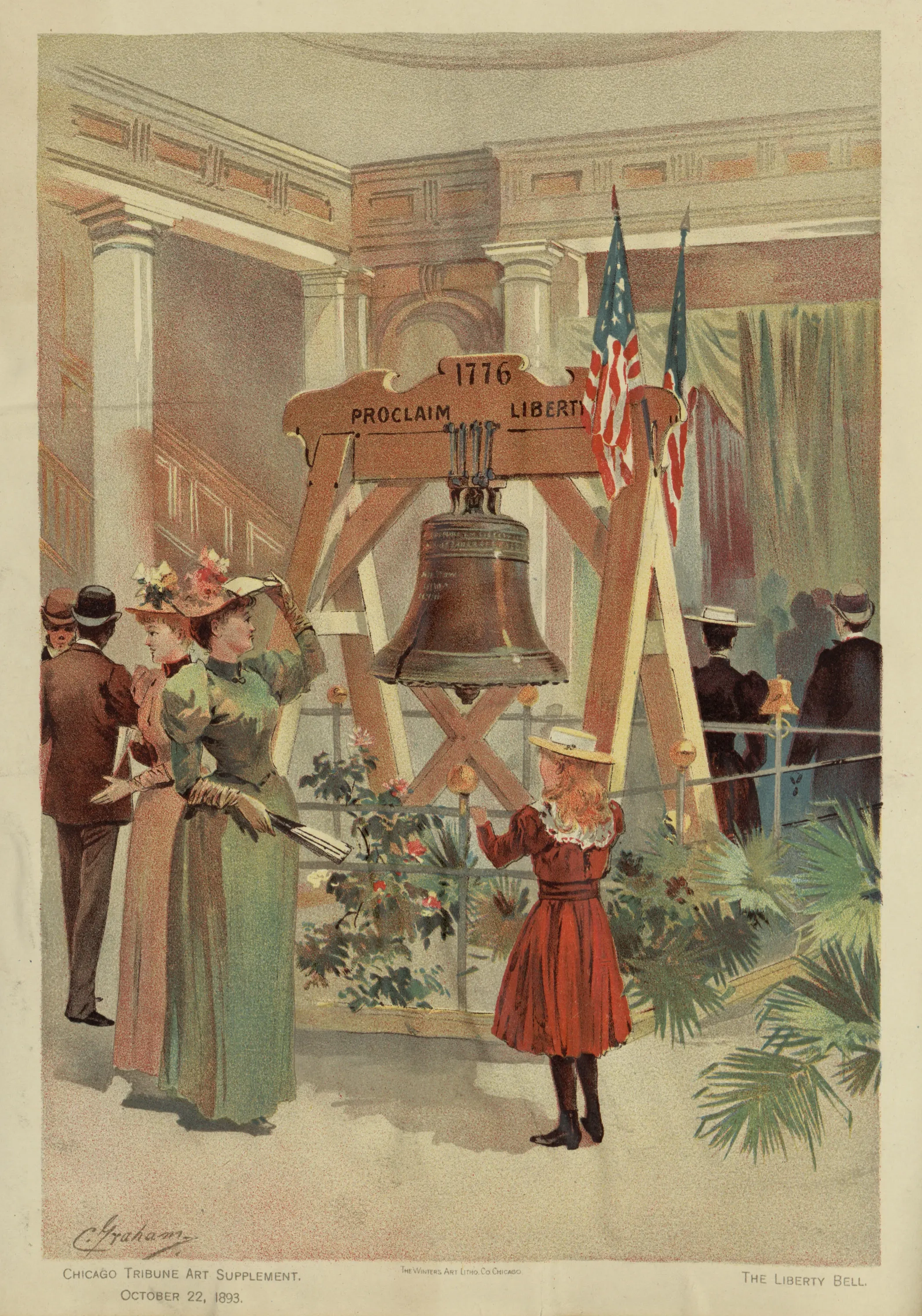

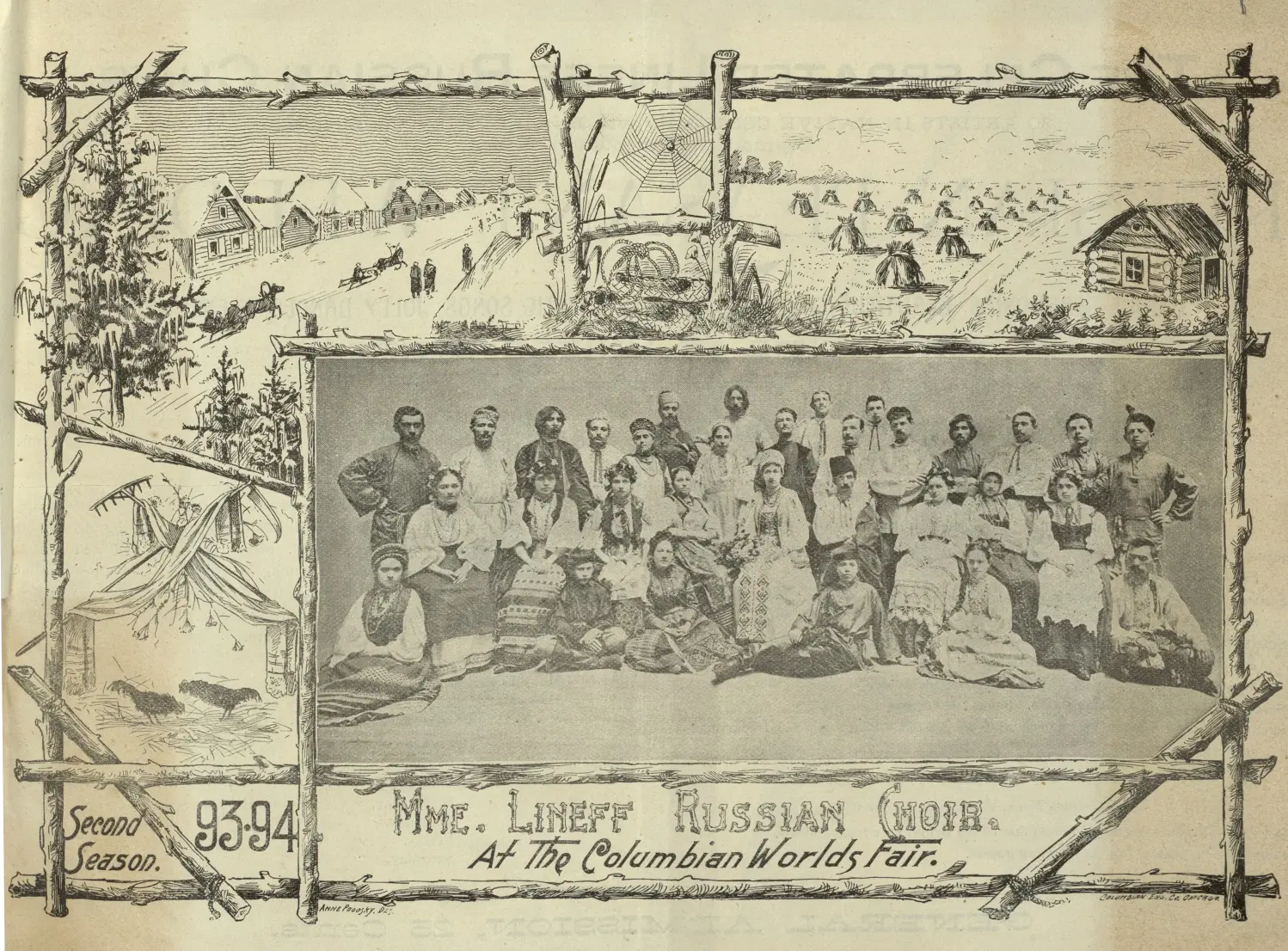

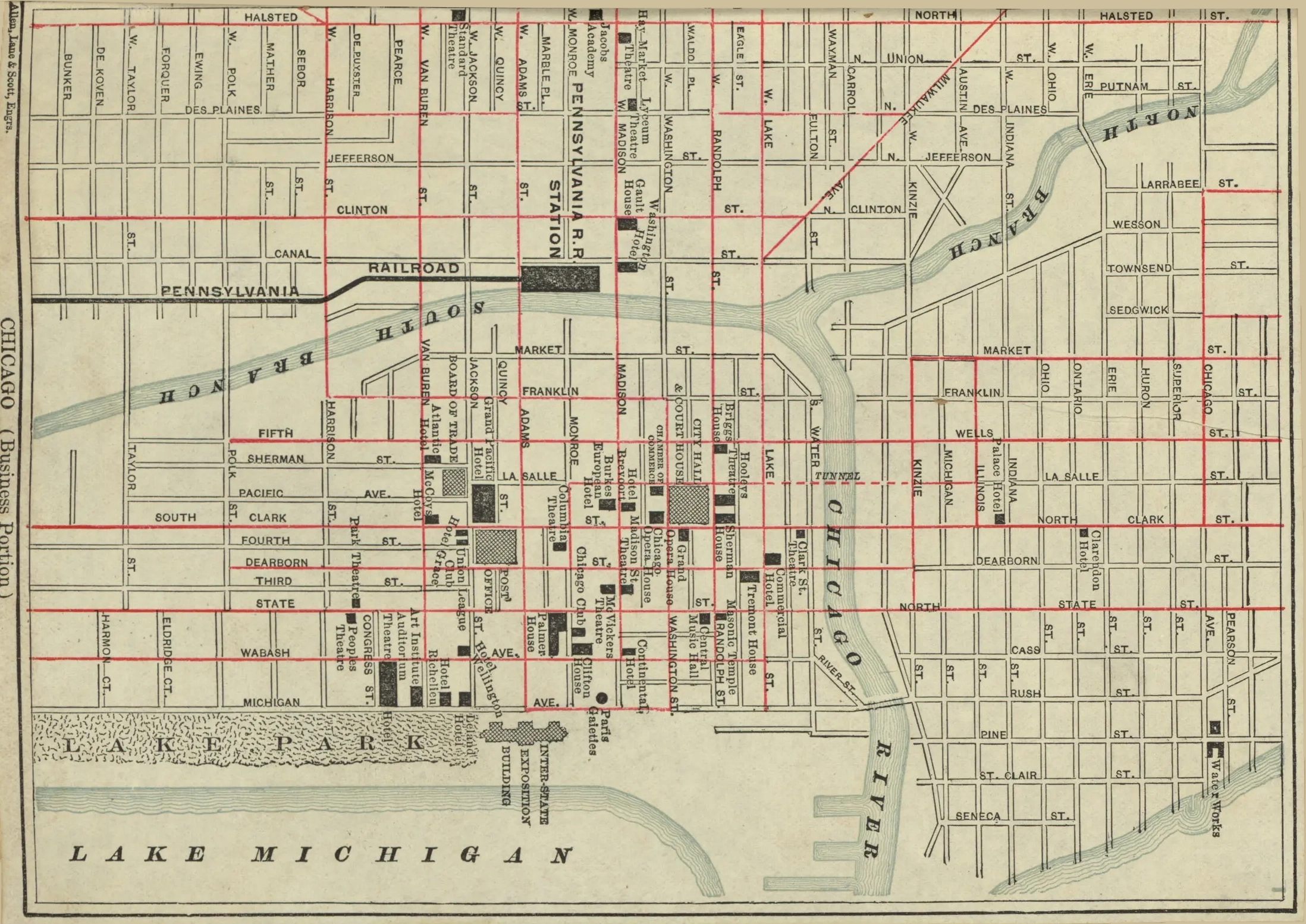

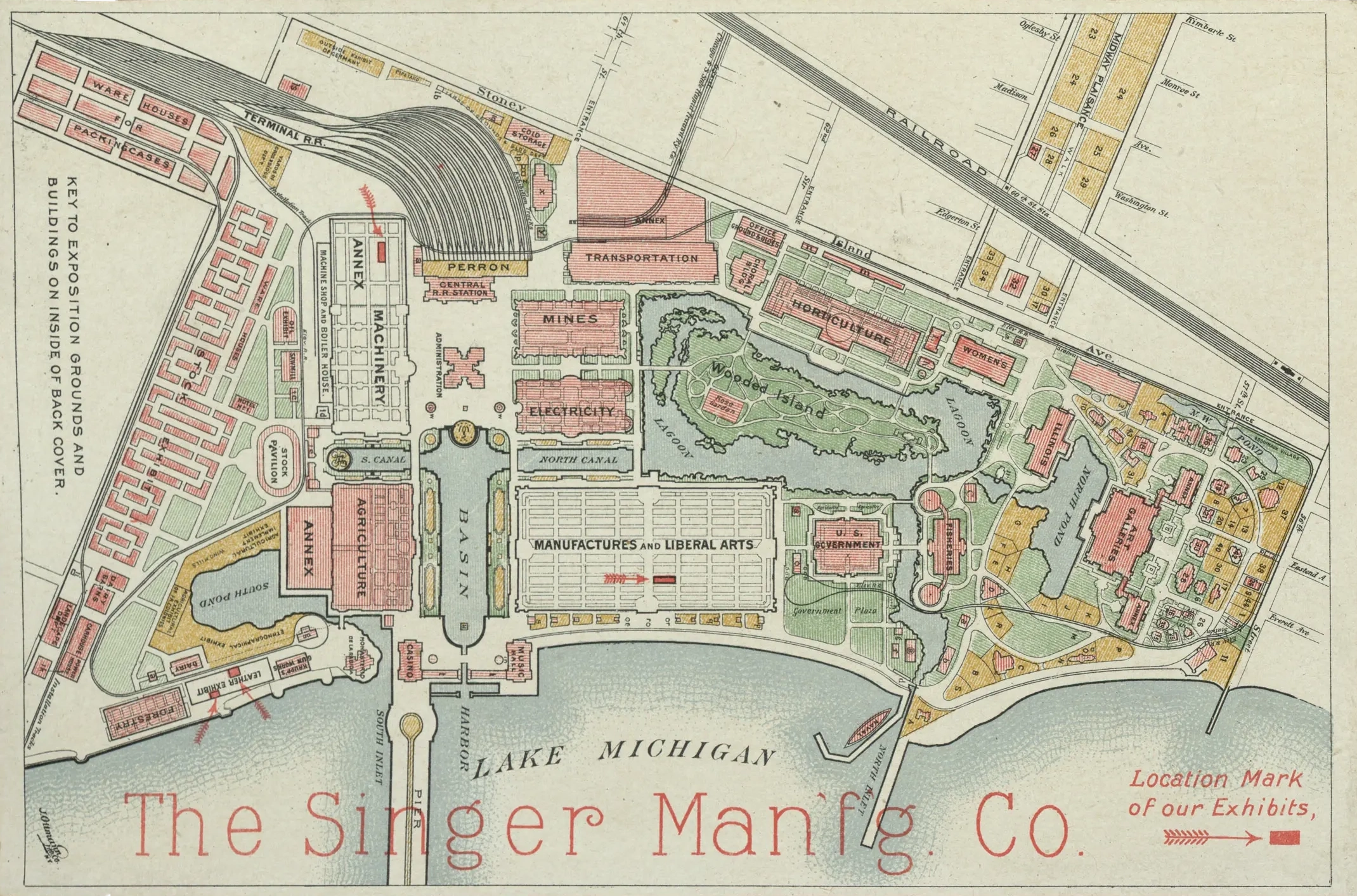

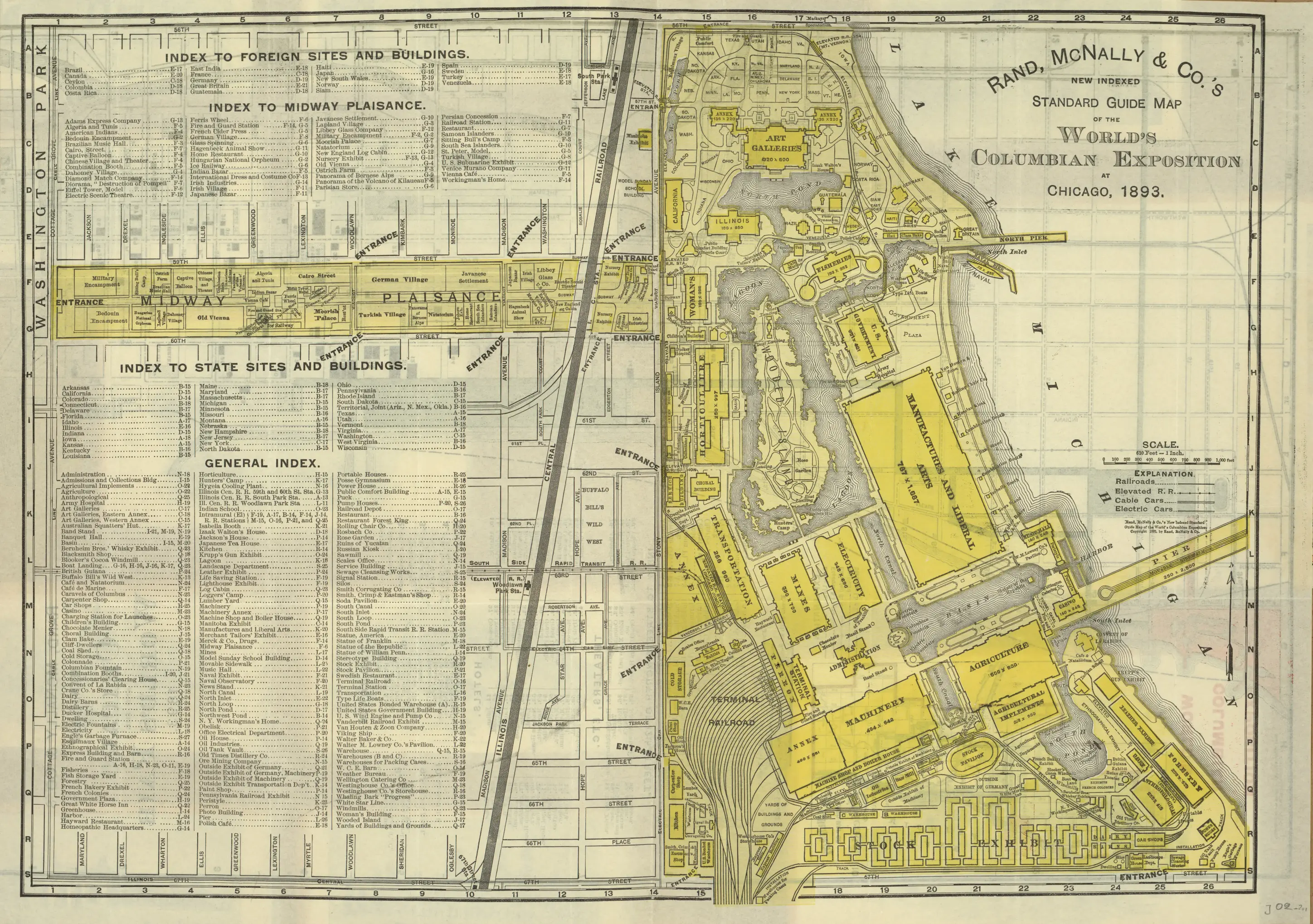

The World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893)

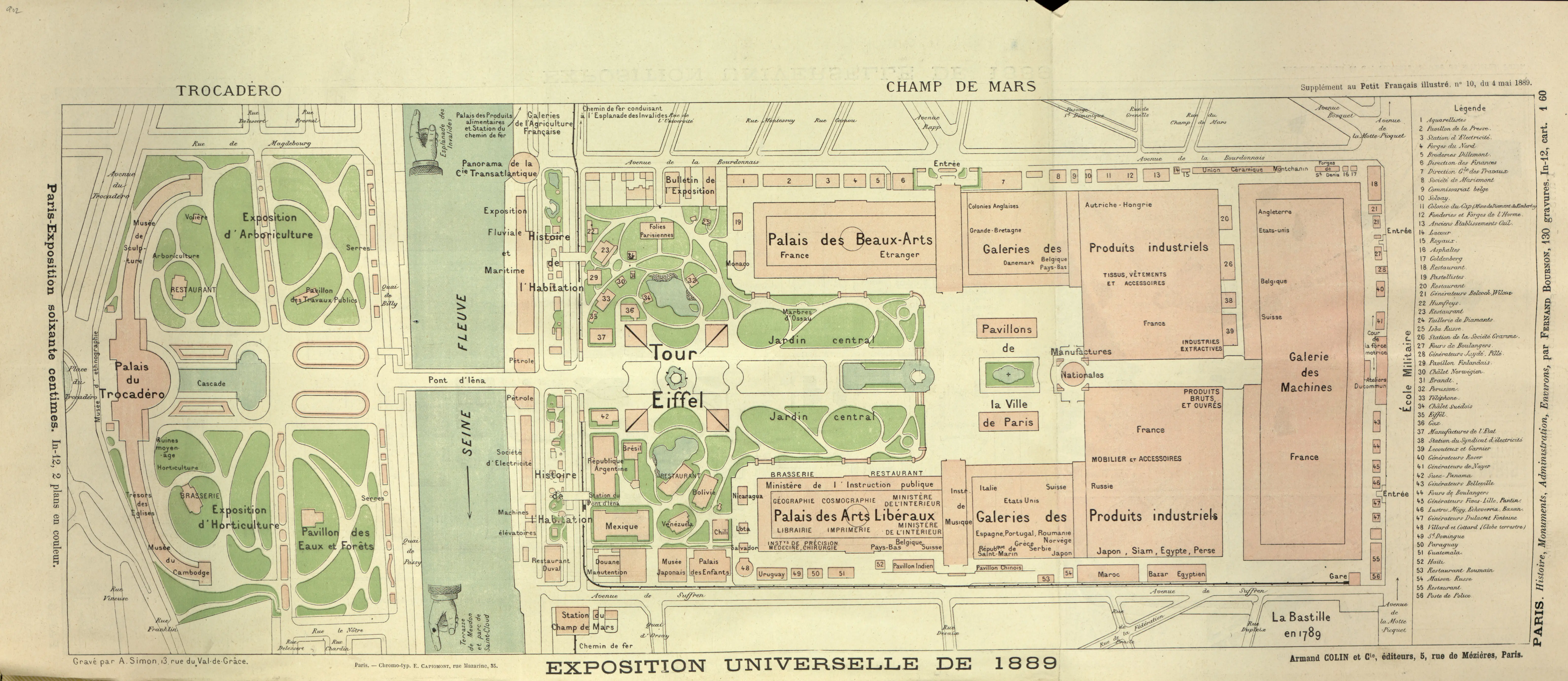

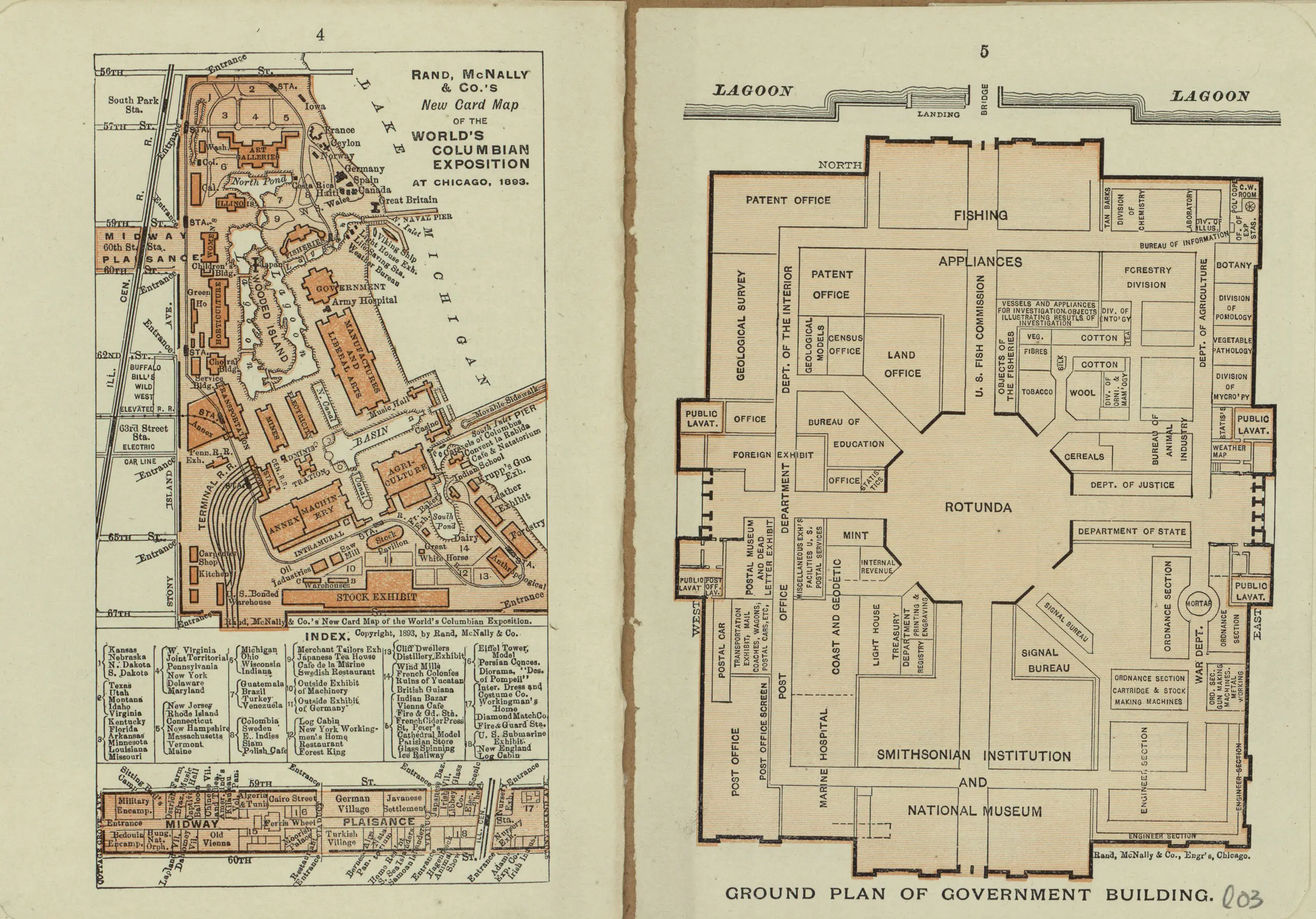

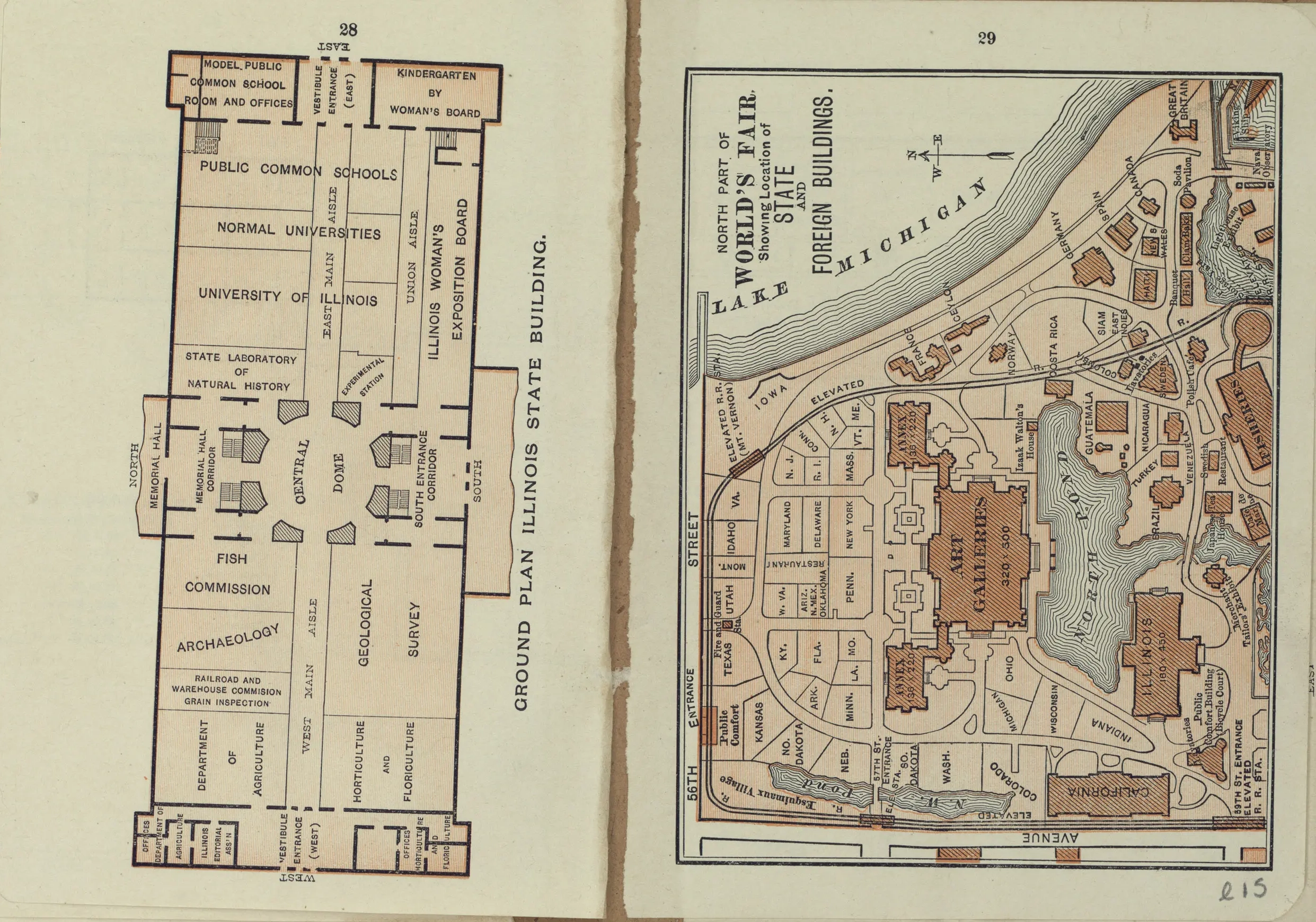

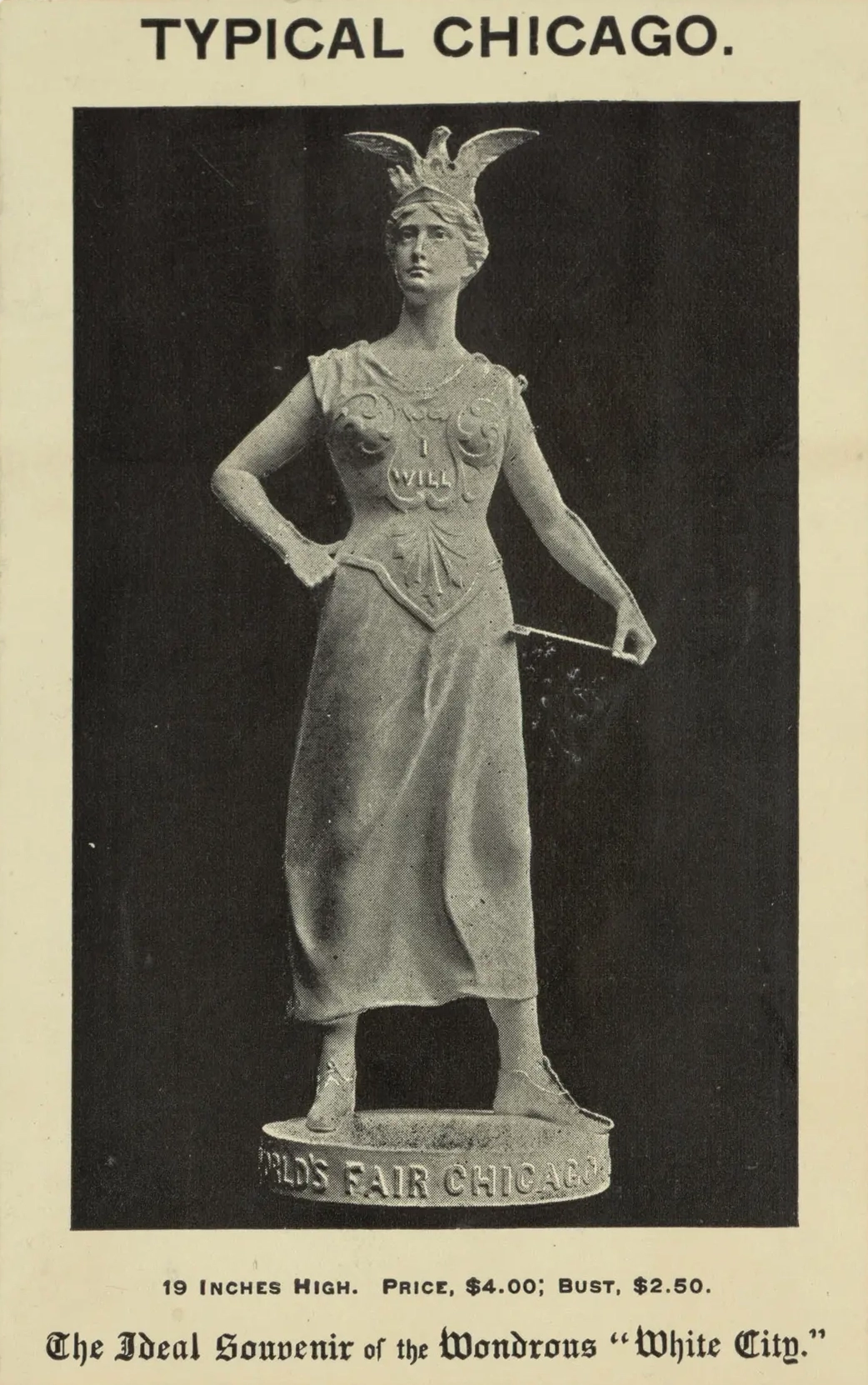

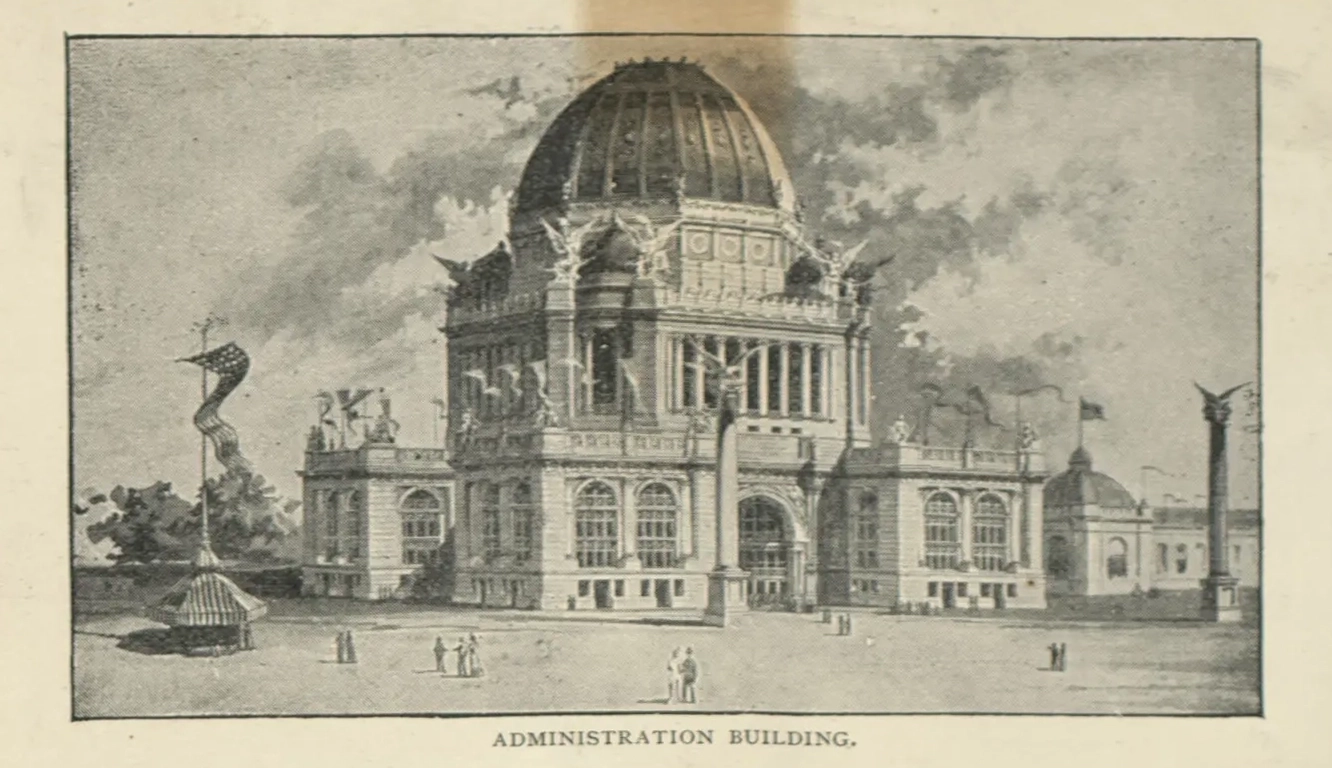

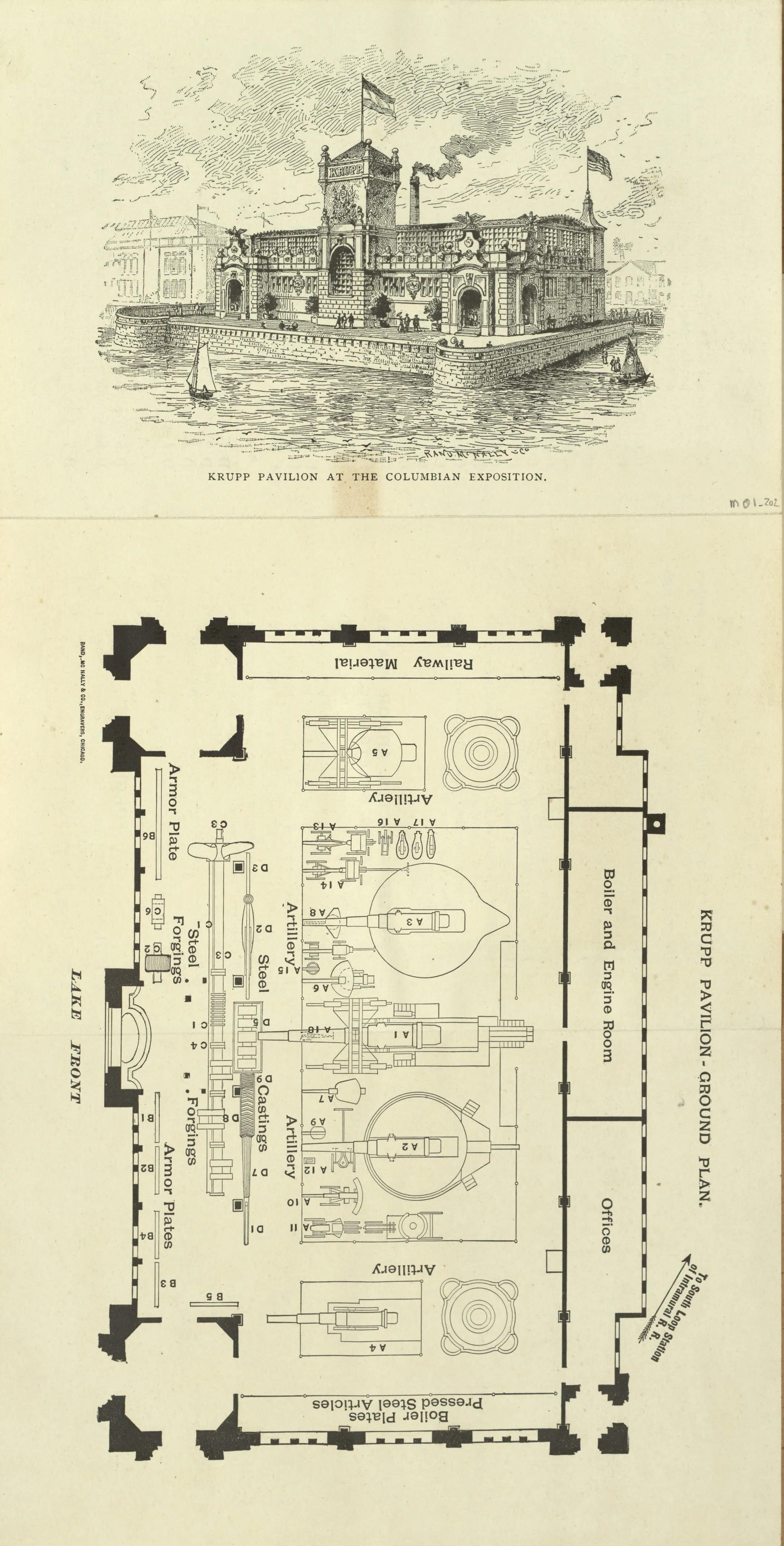

As part of his journey to the United States, Joannes Gennadius visited the exposition in October 1893, from which he kept numerous souvenirs. The World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, was held in Chicago from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World in 1492. At its center was a vast reflecting pool symbolizing Columbus’s voyage across the Atlantic.

The fair was a major social and cultural event, leaving a lasting impact on architecture, the arts, and the broader image of the city of Chicago, as well as on the spirit of American industrial optimism. It also served to demonstrate to the world that Chicago had reborn from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871.

Spanning 690 acres (2.8 km²), the exposition featured nearly 200 new but temporary buildings—predominantly in the neoclassical style—alongside canals, lagoons, and displays of people and cultures from 46 nations. More than 27 million visitors attended during its six-month run. Its scale and grandeur far surpassed that of any other world’s fair of the time, making it a symbol of emerging American exceptionalism.