SOPHIA AND HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN

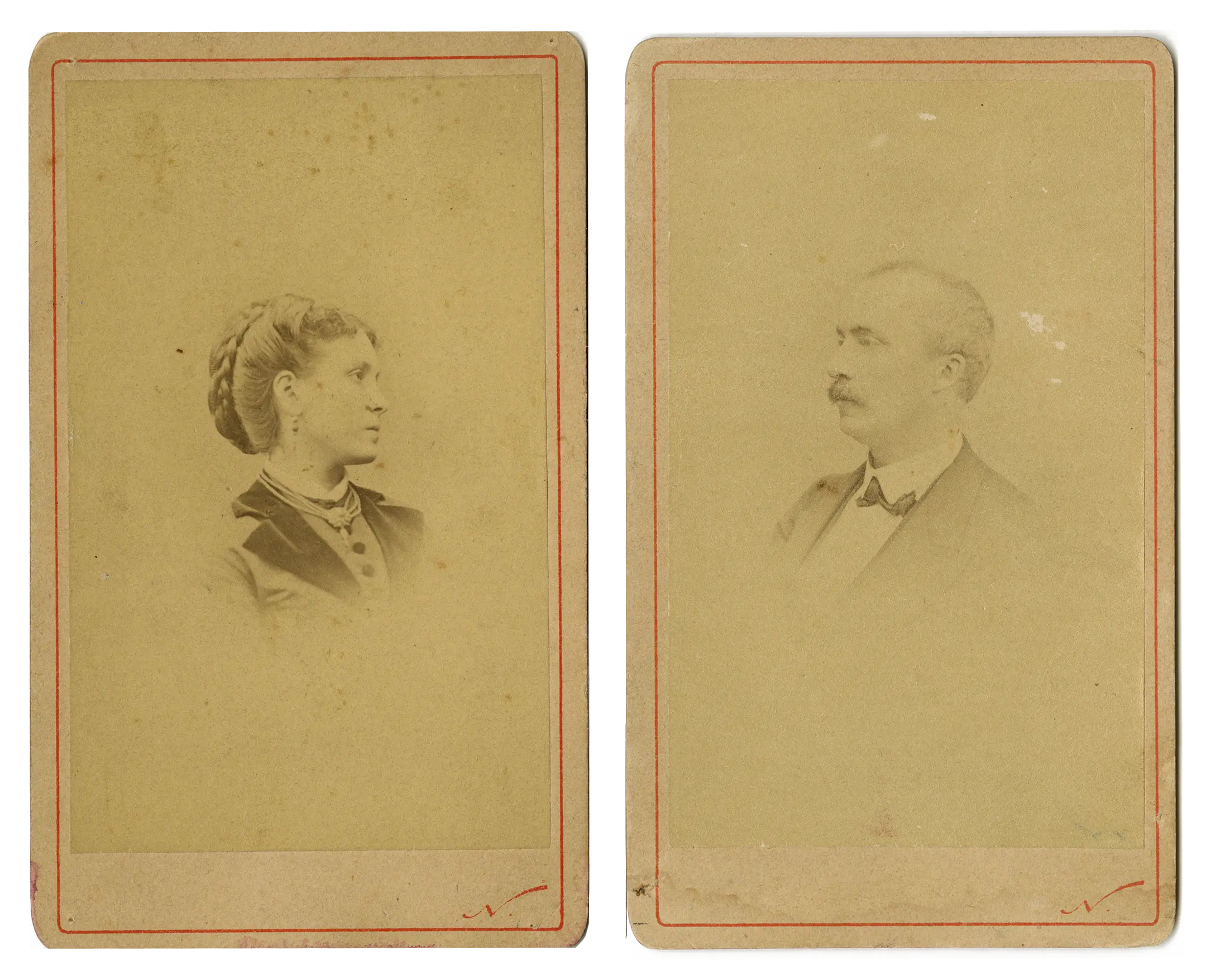

Heinrich Schliemann came to Greece in 1869, having sold his businesses in Russia and divorced his Russian wife. Schliemann was looking for a new partner to share his dream of excavating the Homeric citadels of Troy and Mycenae, so as to prove that the Iliad was not a fairy-tale

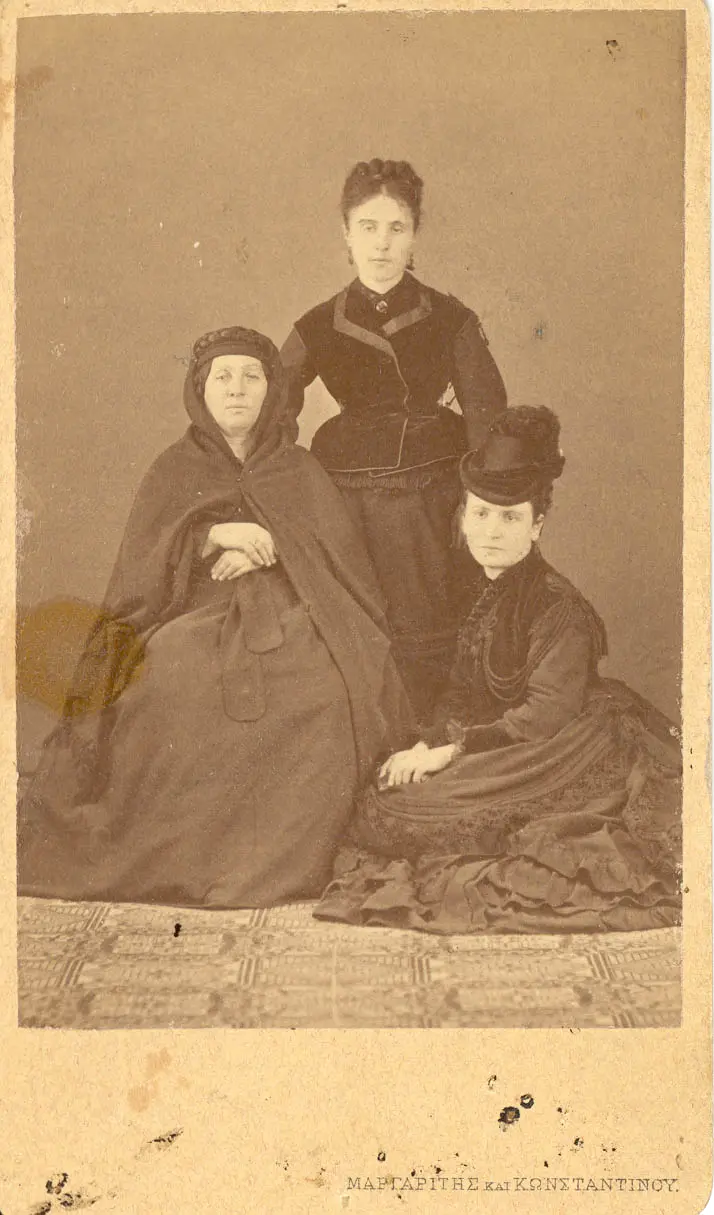

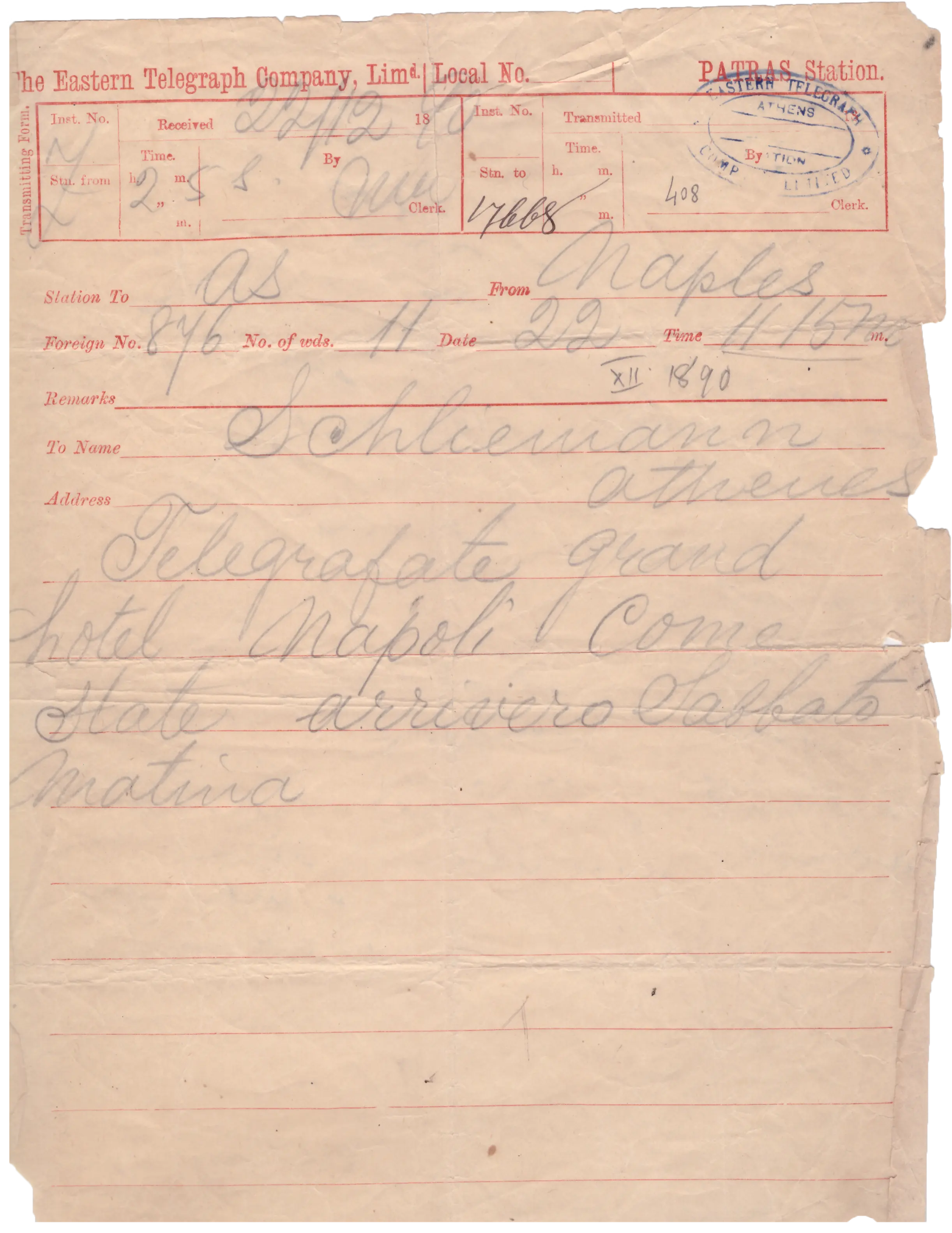

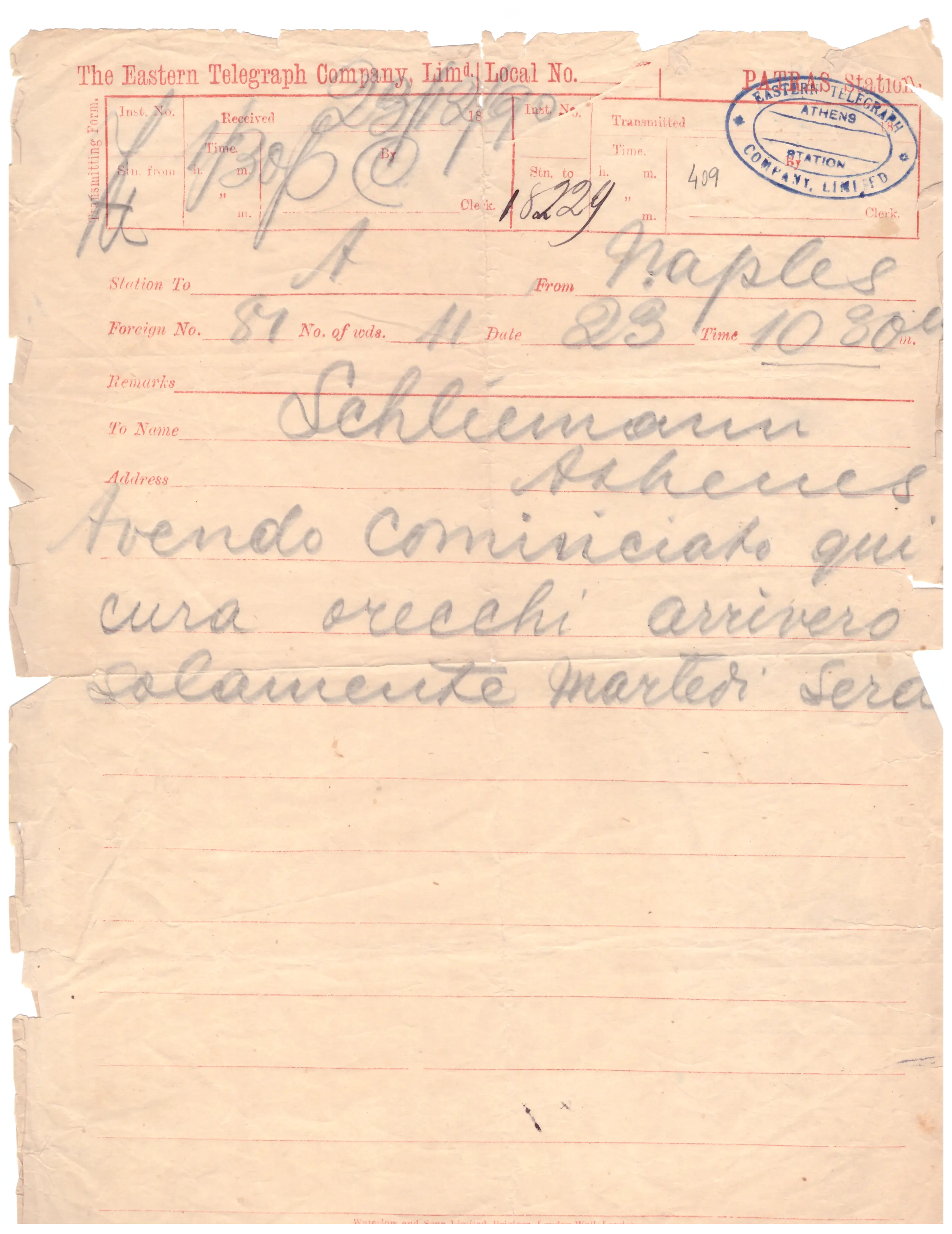

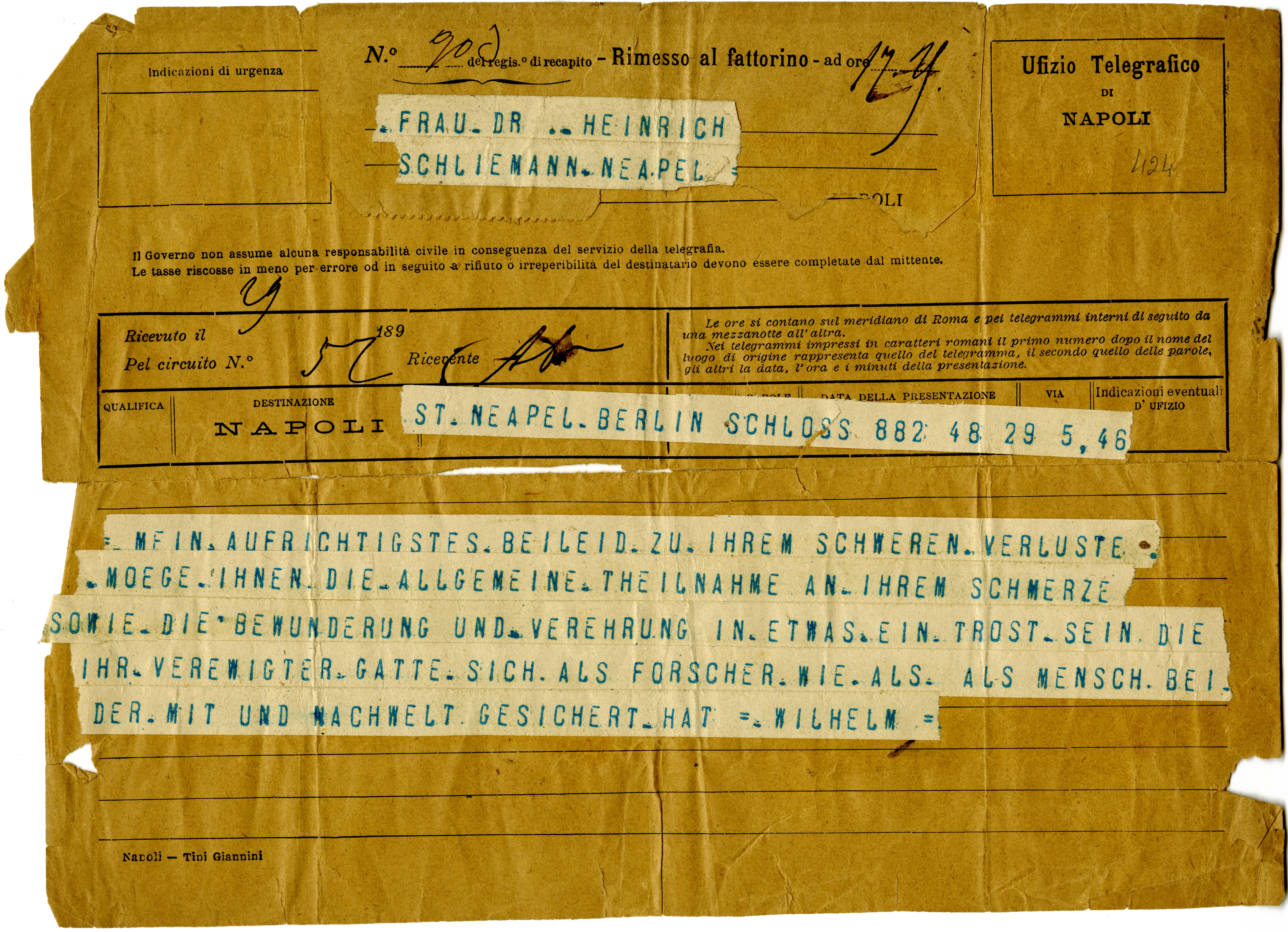

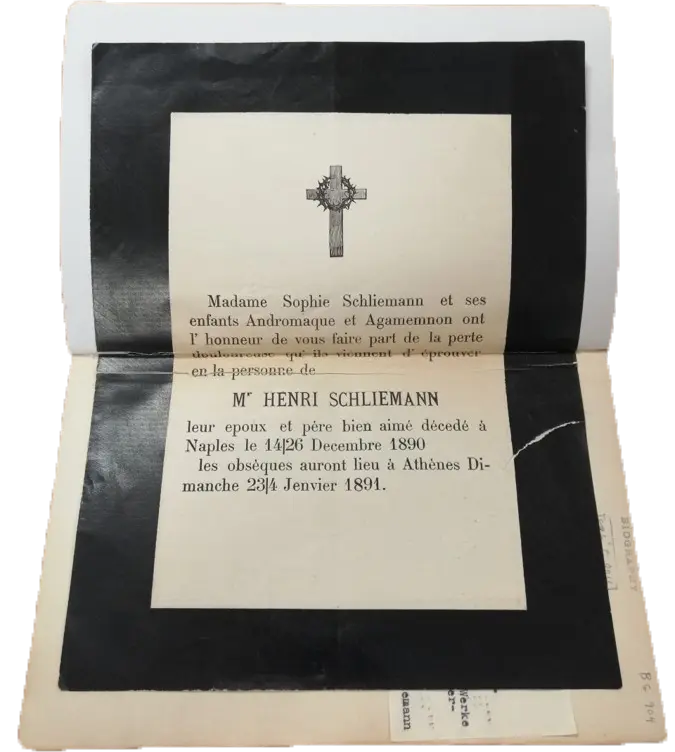

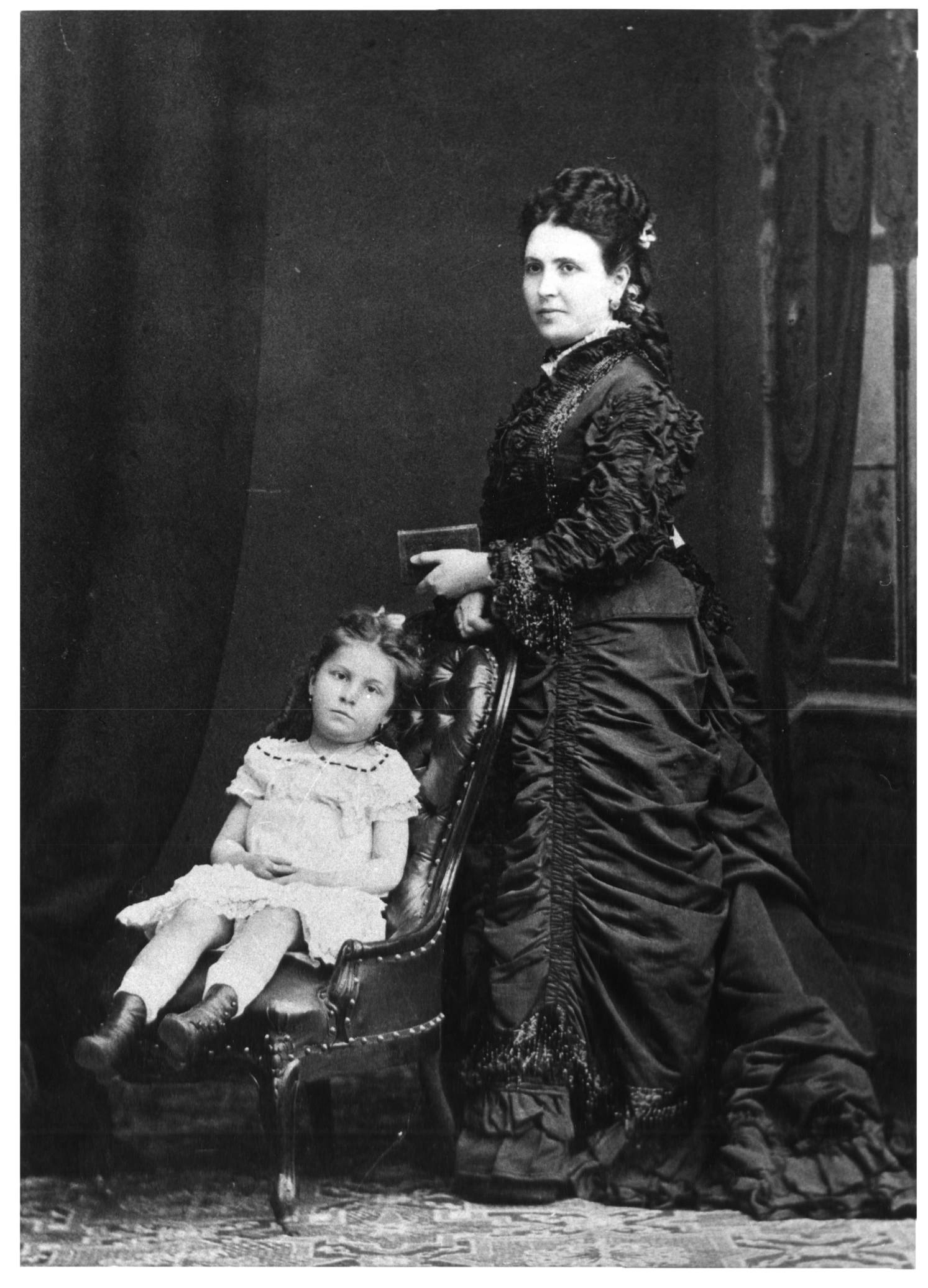

In September 1869 Heinrich married Sophia Engastromenou. He was 48 years old, and she was 18. Following an unsuccessful honeymoon, in the course of which the couple were on the verge of divorce, Schliemann left for Troy to start excavating. The couple did not separate, and in fact they became famous for their discoveries, remaining together till Heinrich's death in 1890. In 1936 their children, Andromache and Agamemnon, donated their Papers to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

The present digital presentation aims to provide a visual record of the Schliemanns, using photographs and letters from the archive, and complementing the publications by Eleni Bombou-Protopapa, Sophia Engastromenou-Schliemann: Letters to Heinrich (2005) and Danae Koulmasi, Schliemann and Sophia: a love story (2006).

1. AN ARRANGED MARRIAGE: BRIDE AND GROOM ON THE VERGE OF DIVORCE

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers

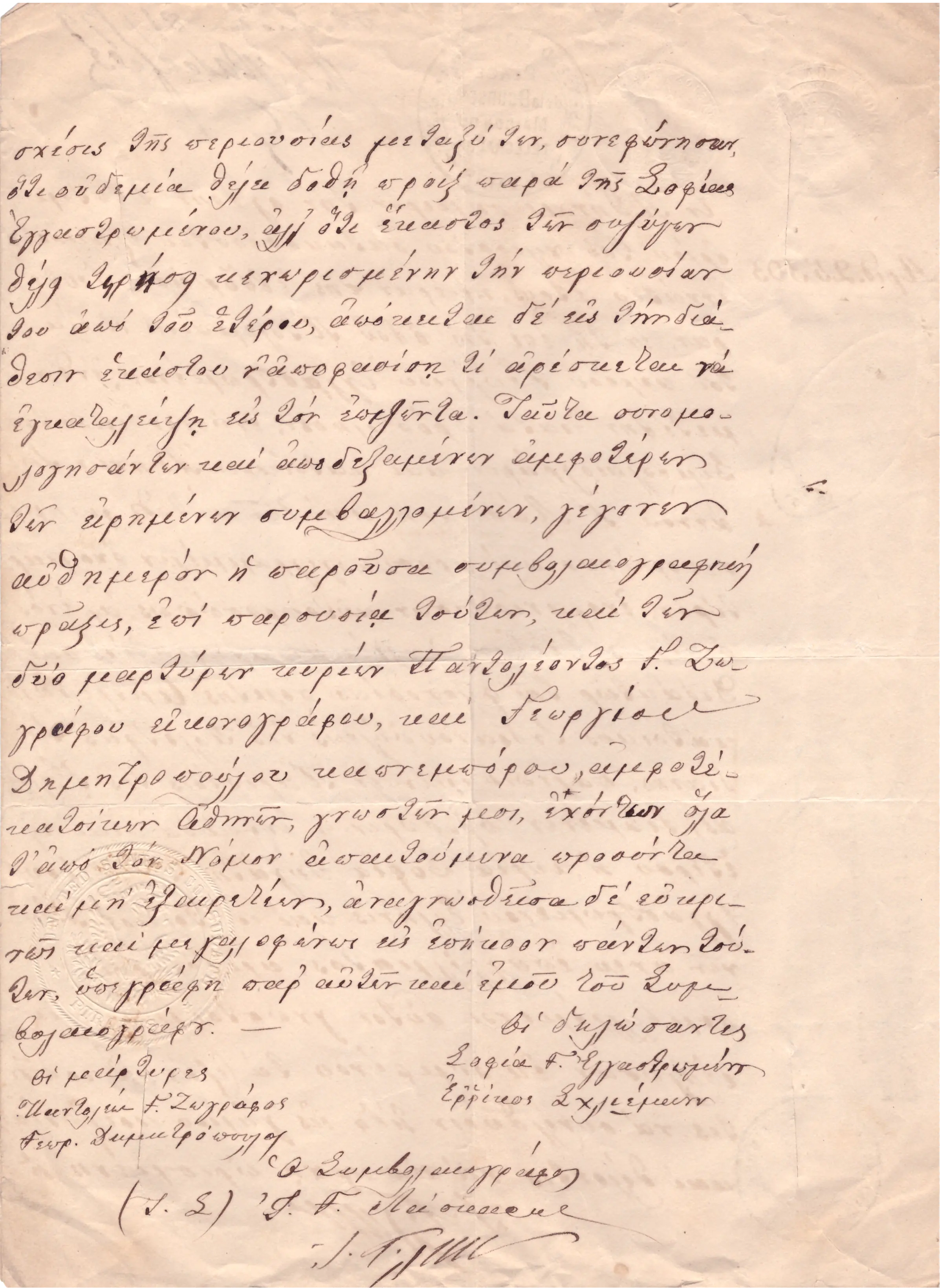

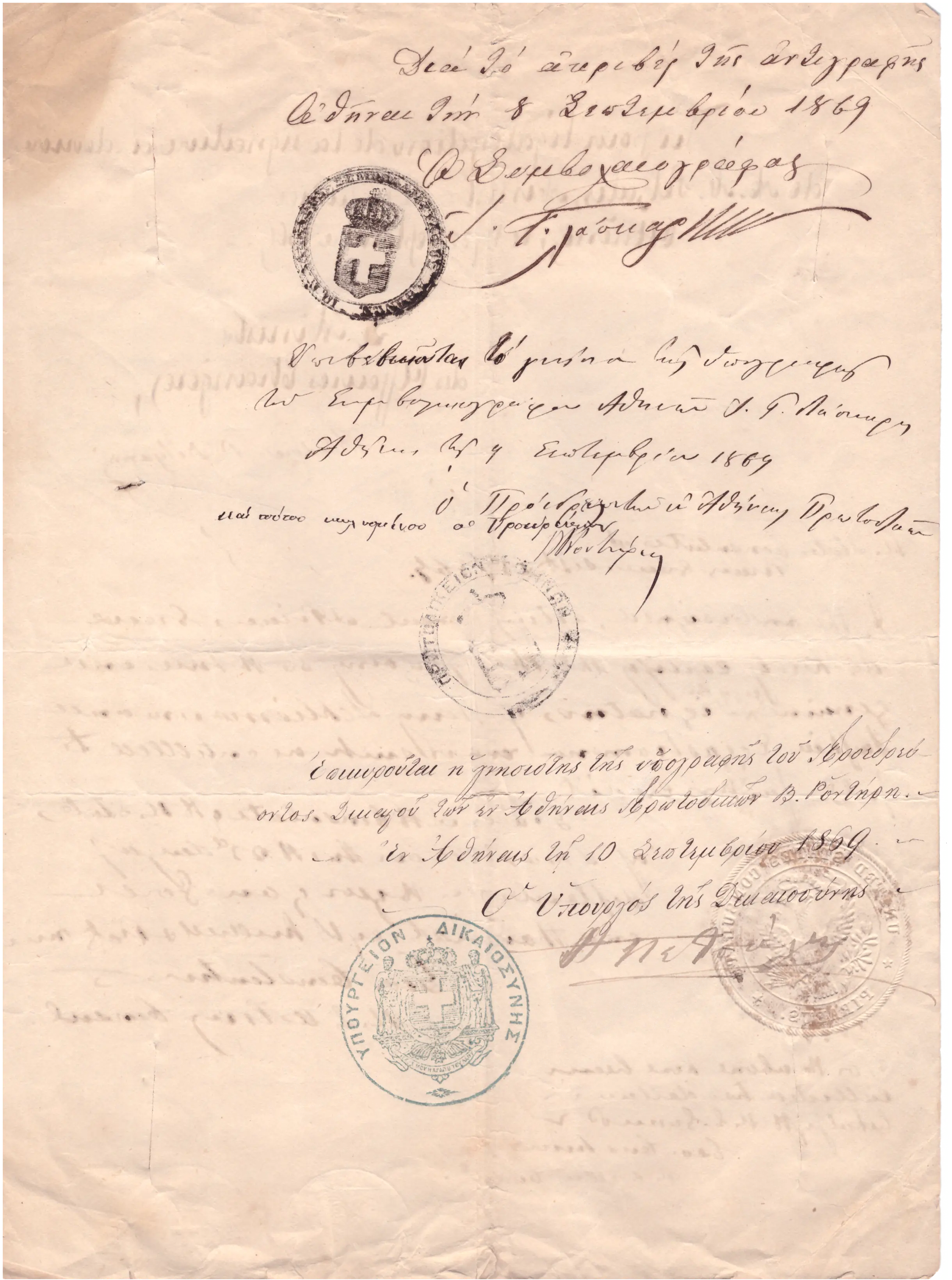

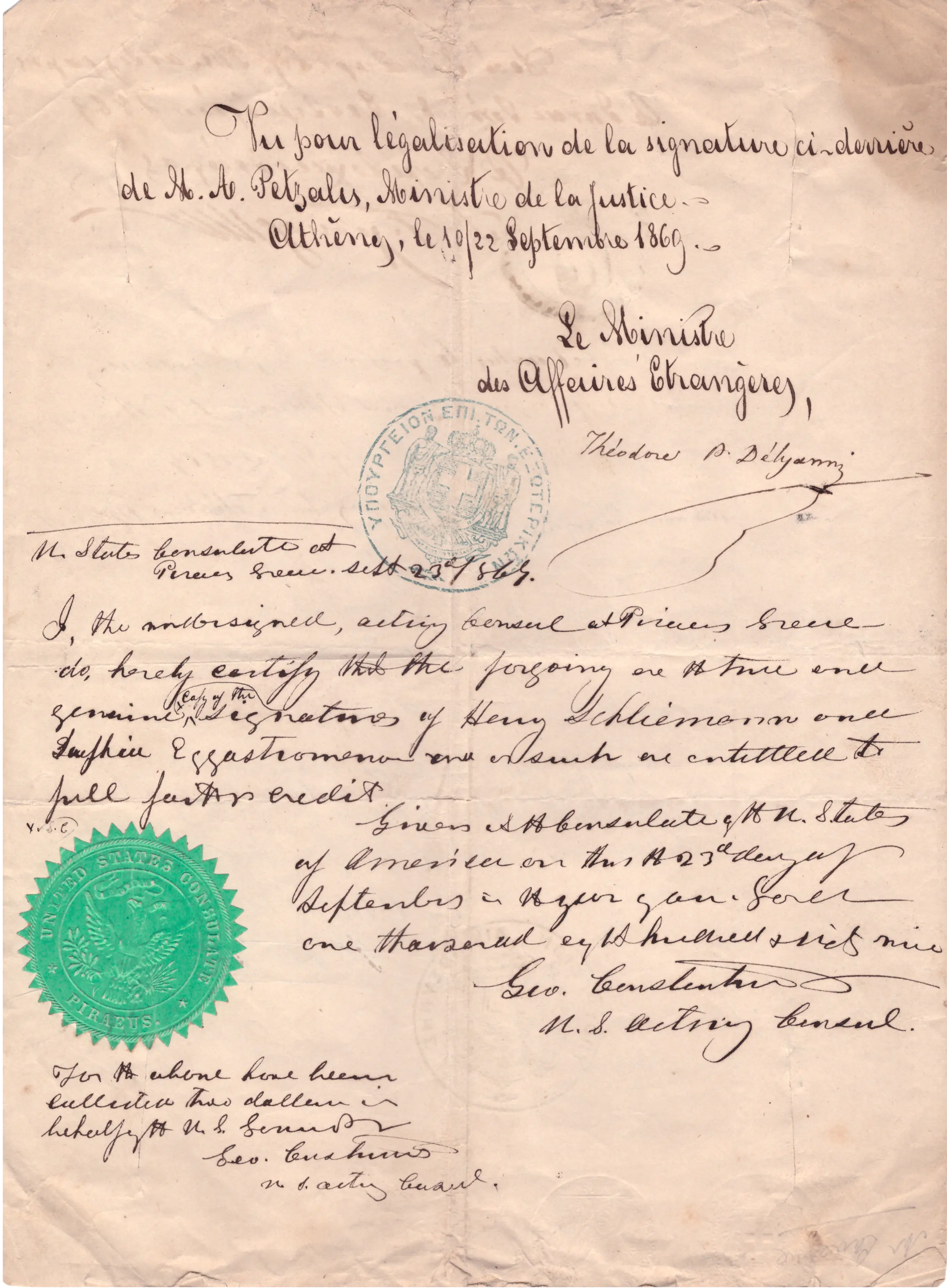

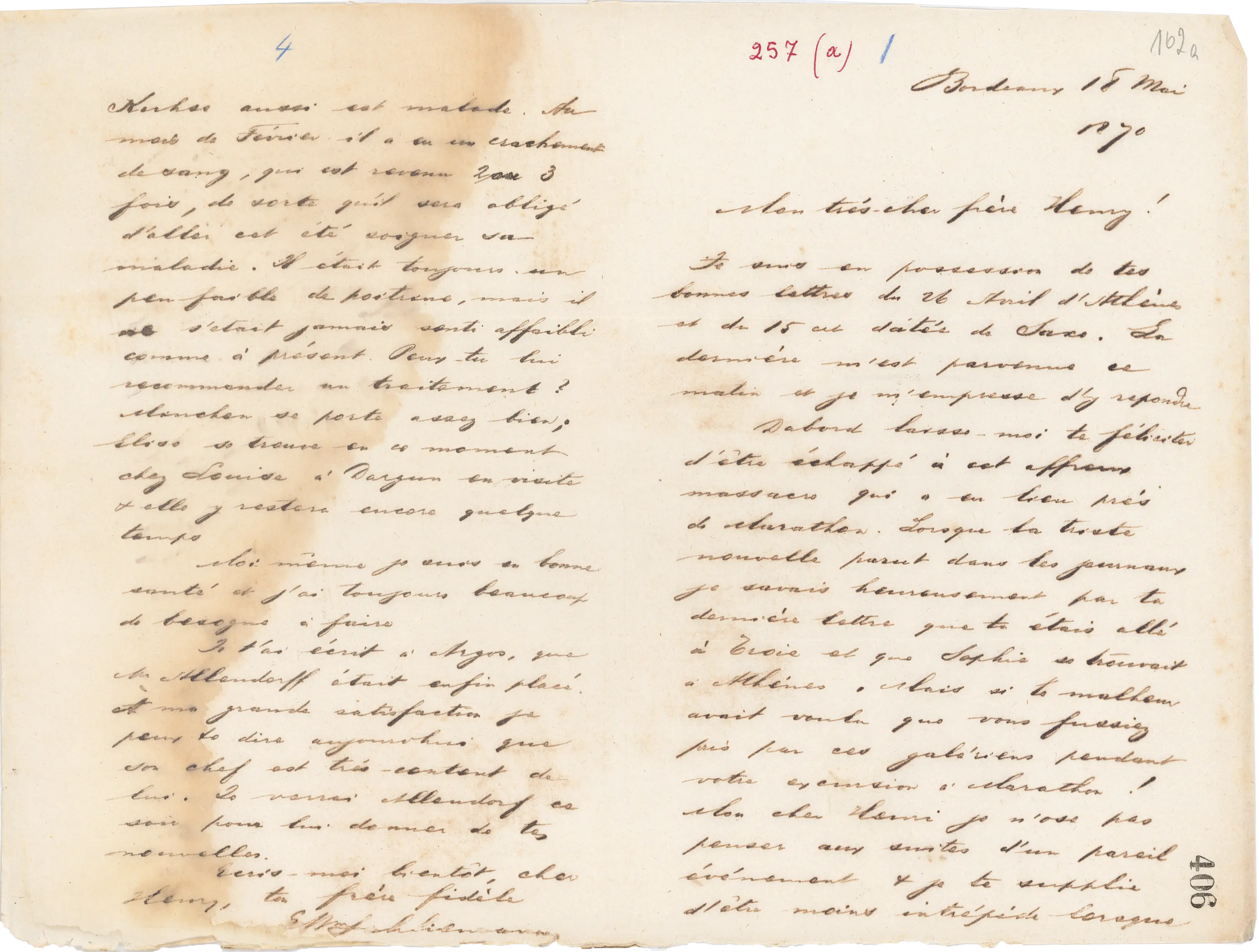

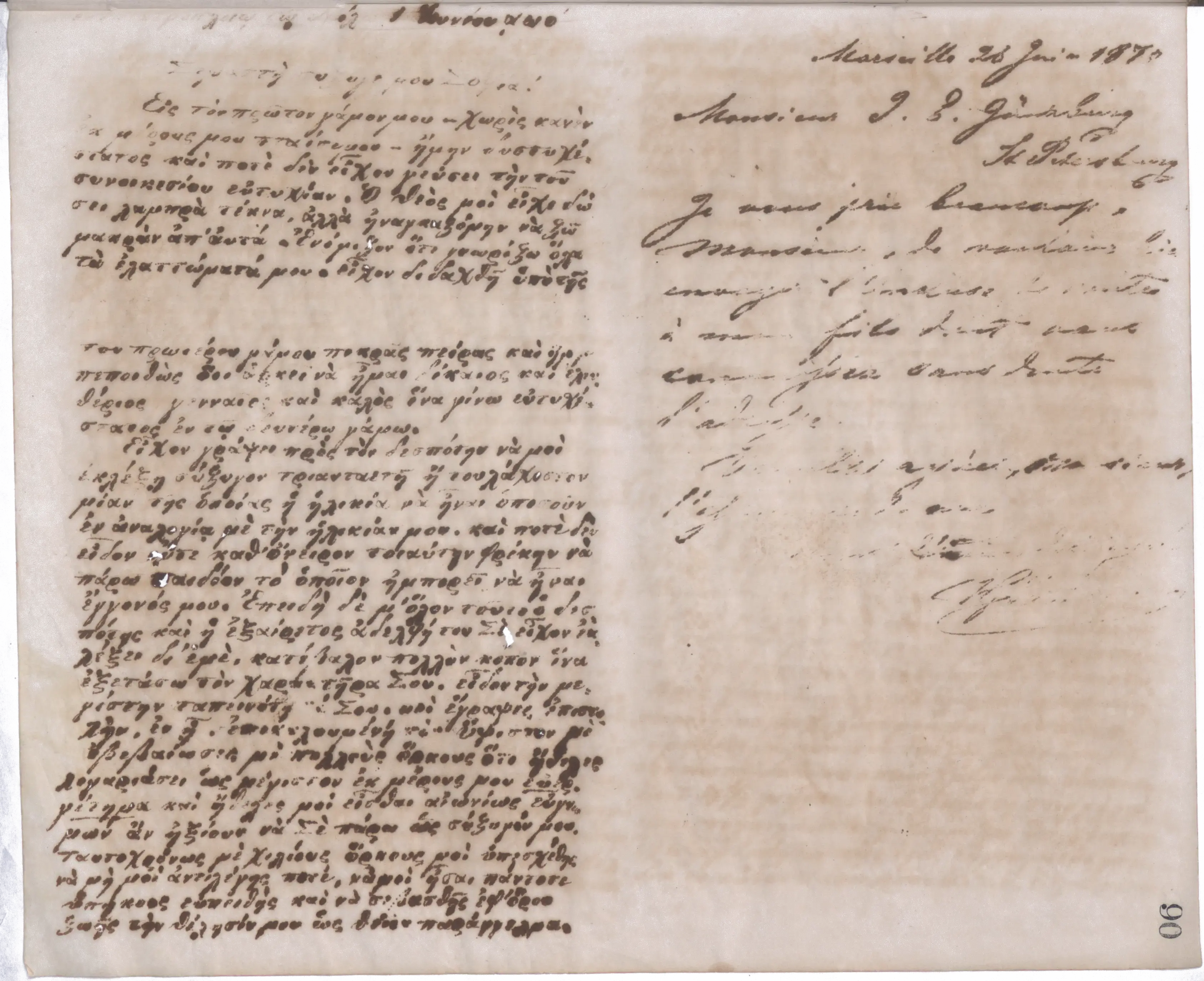

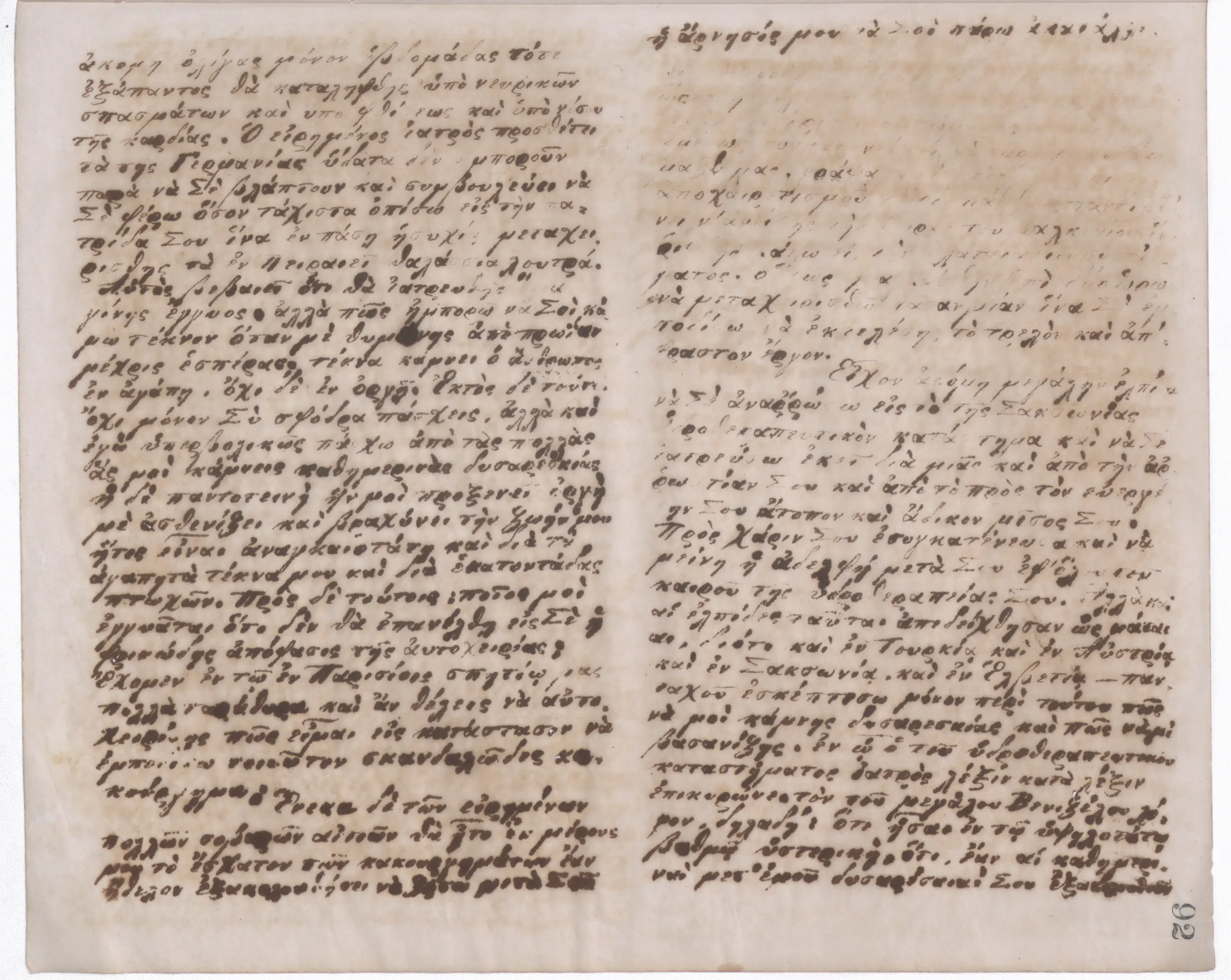

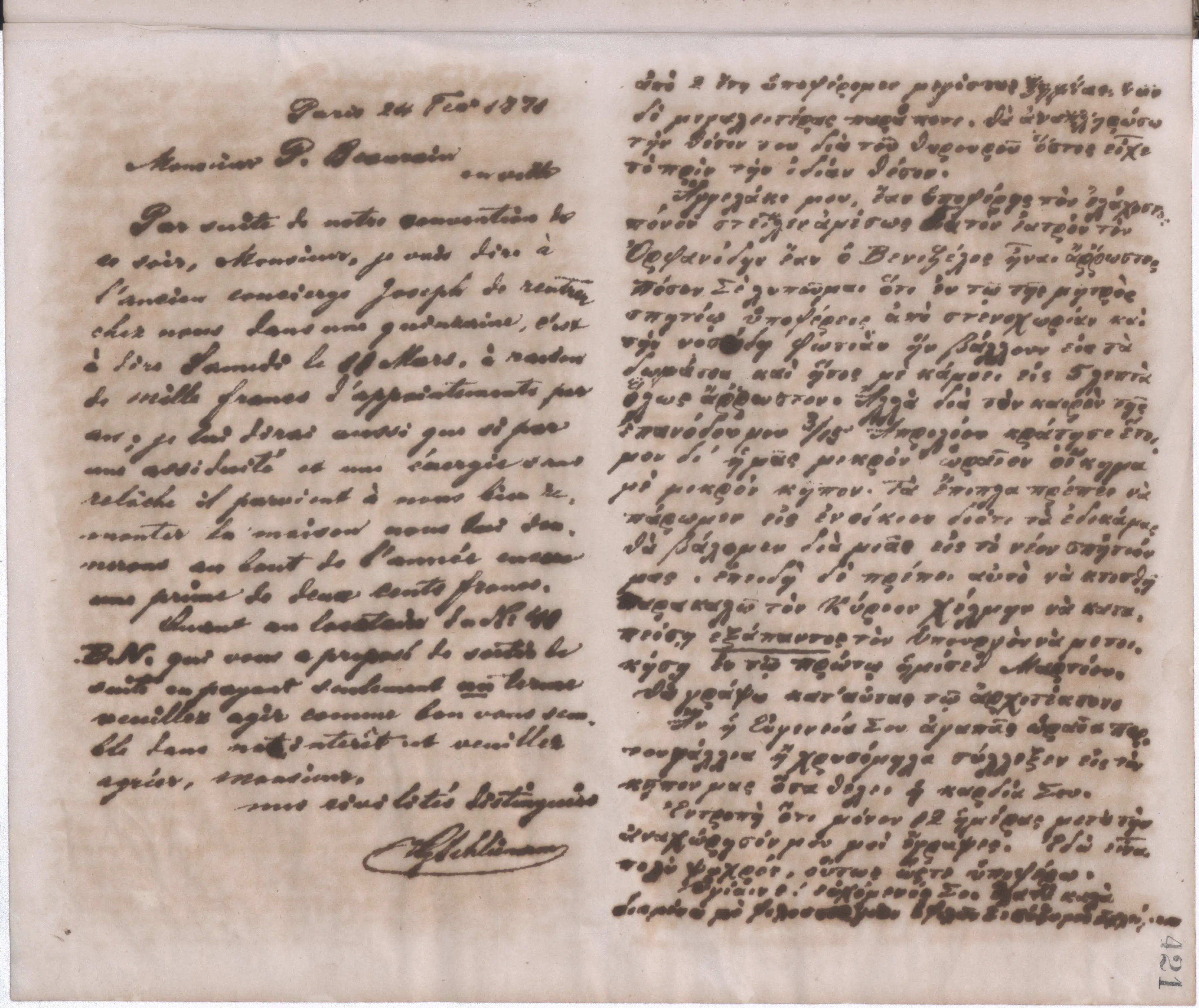

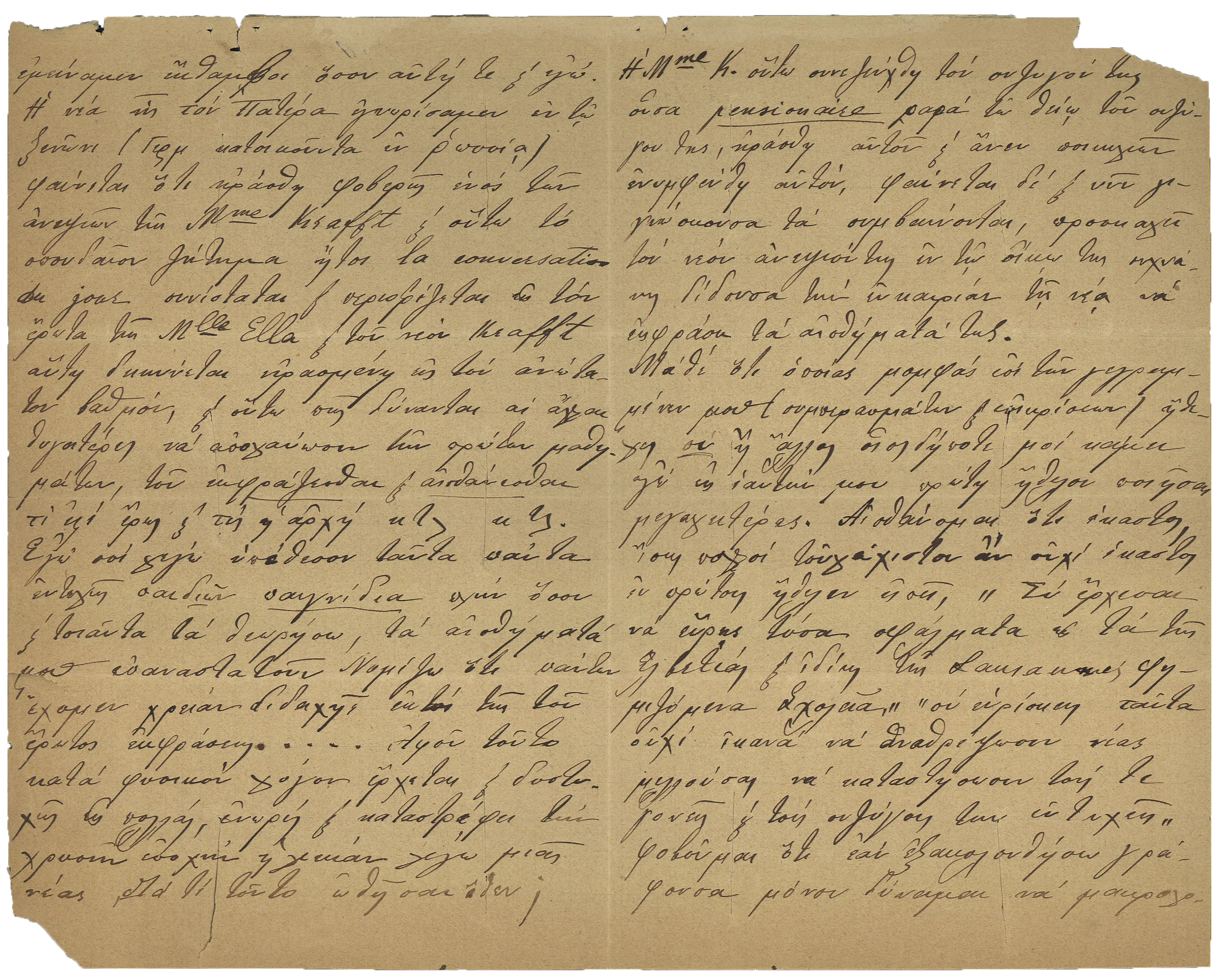

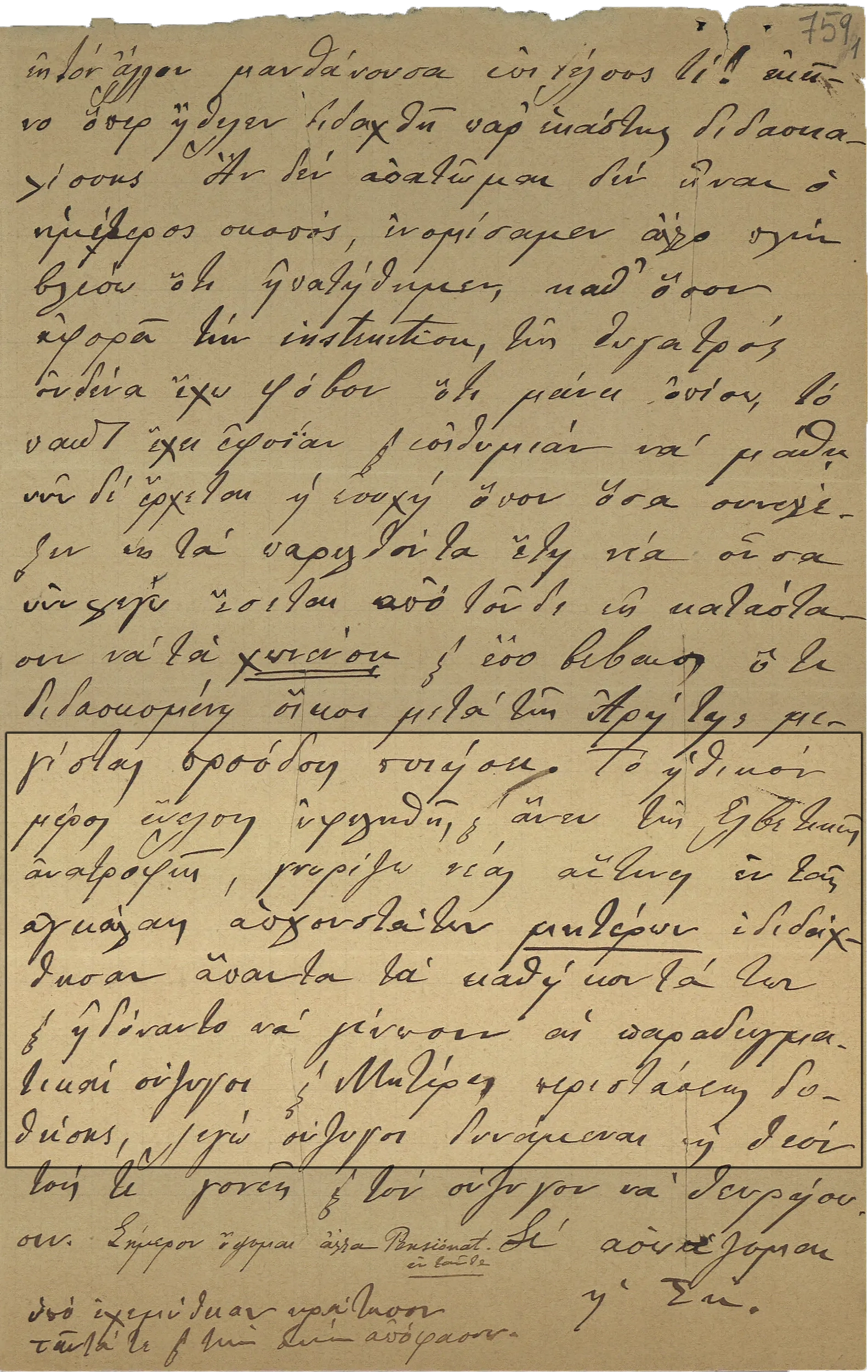

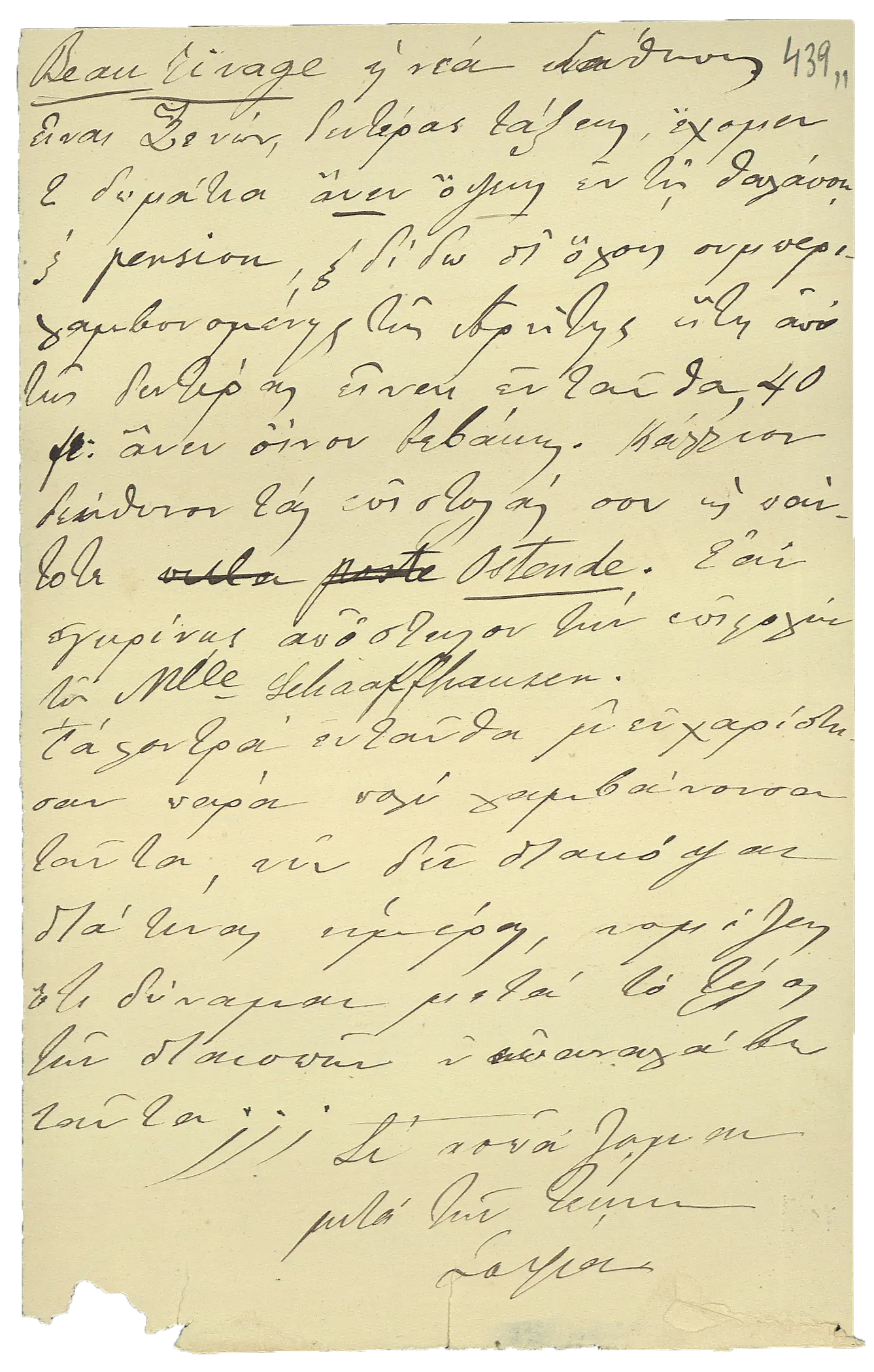

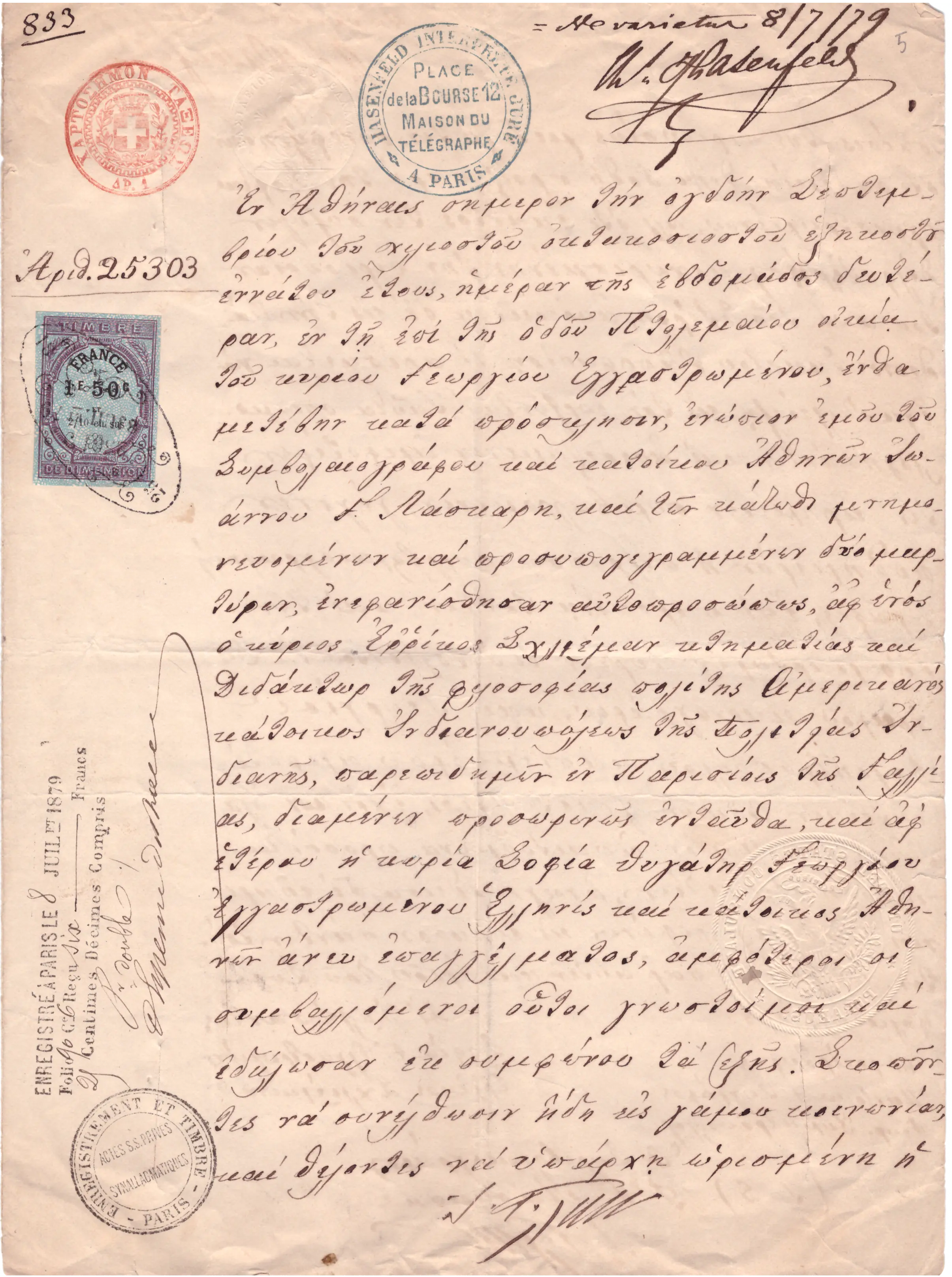

On the 21st of September 1869, Heinrich Schliemann, a wealthy German businessman, married Sophia Engastromenou in Athens. Heinrich was 47 and Sophia was 17. It was an arranged marriage, and a second marriage for Schliemann, who had just divorced his Russian wife of 20 years, Ekaterina Lyschina. Schliemann, having liquidated his business enterprises in Russia, was seeking a new way of life, in order to prove that the Homeric cities of Troy and Mycenae were real and not mythical. The choice of a Greek wife was part of this 'dream'. The couple signed a pre-nuptial agreement to the effect that during Heinrich's lifetime Sophia would have no claim on his fortune.

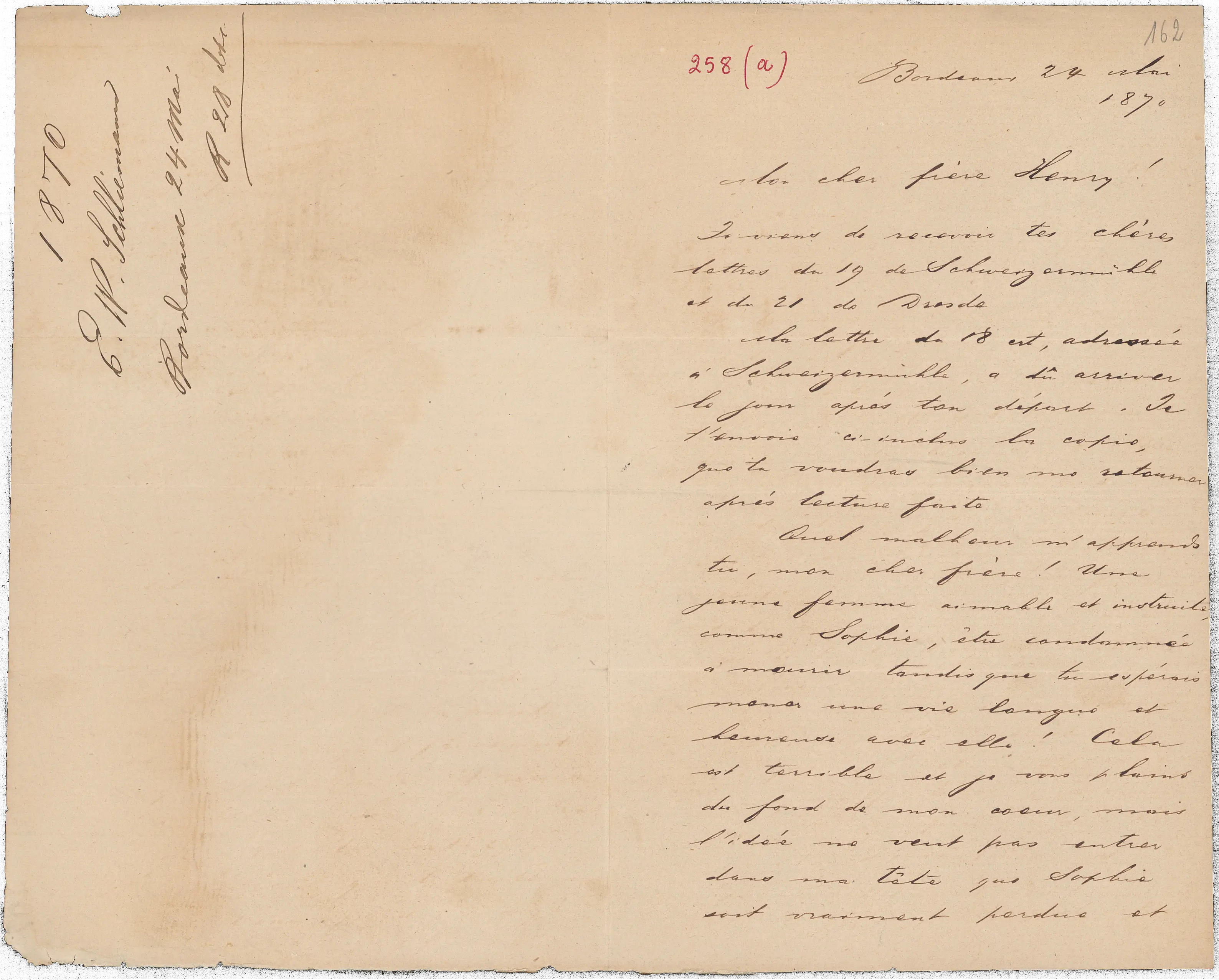

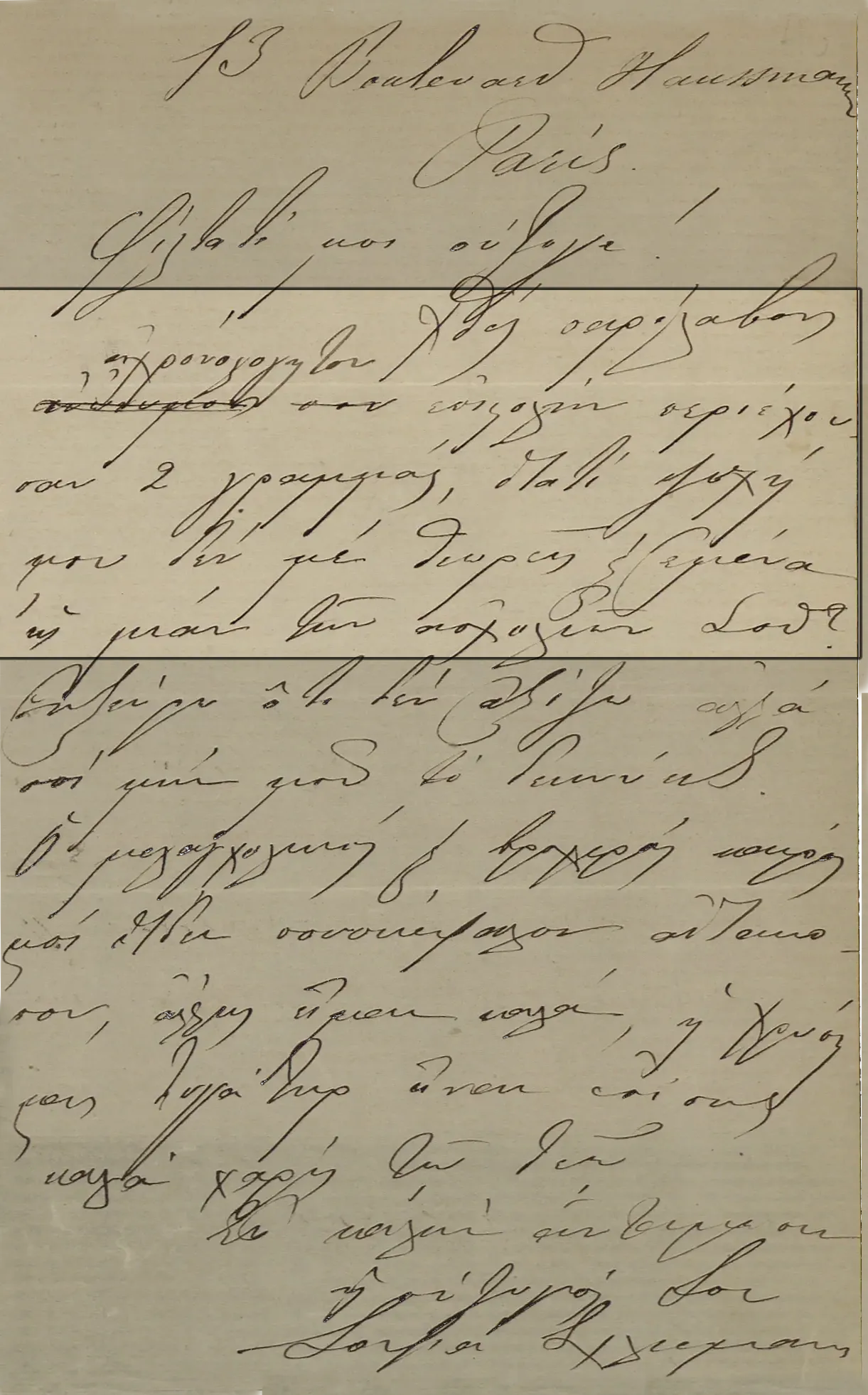

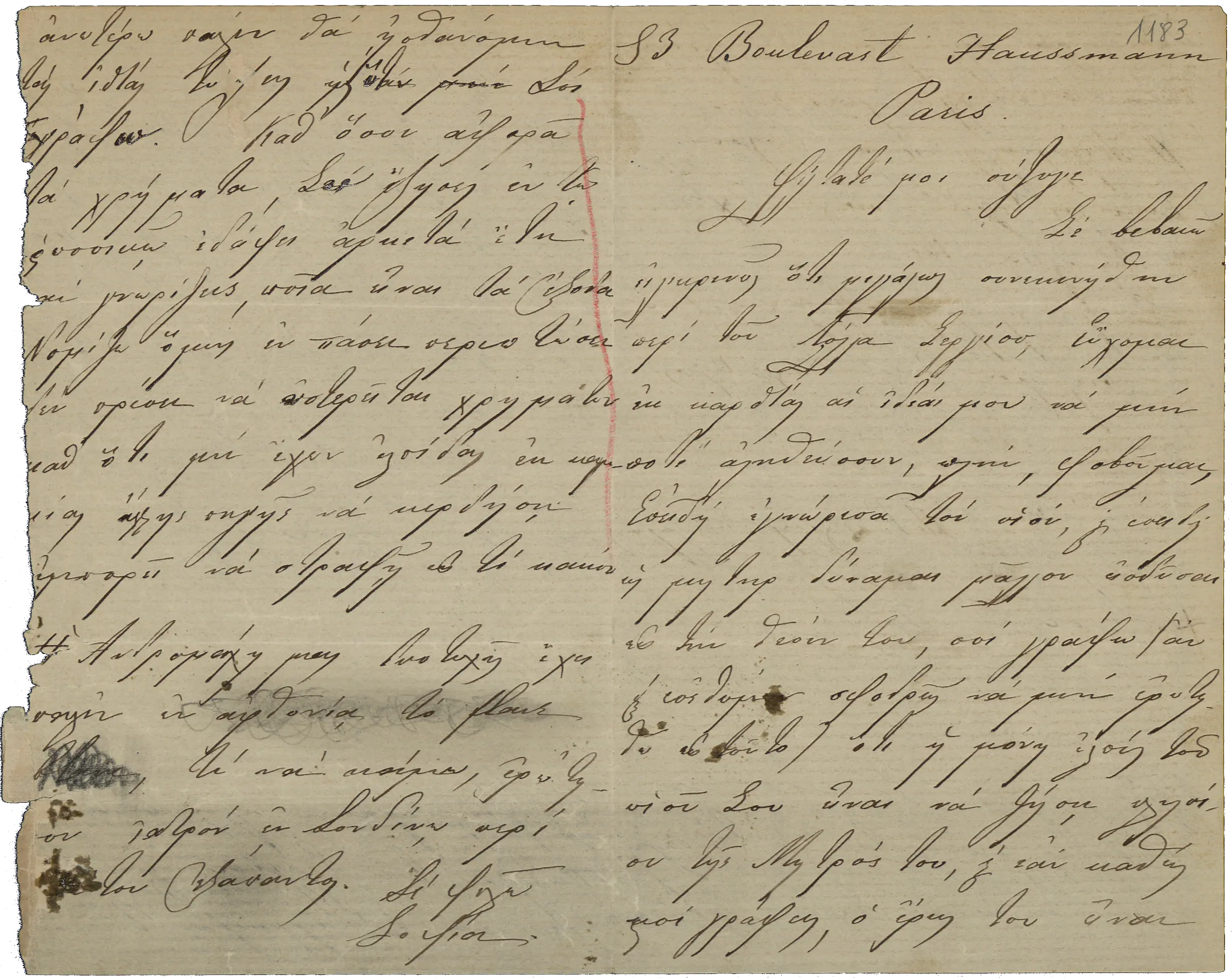

After an extended and disastrous honeymoon in Europe, during which Heinrich tried unsuccessfully to introduce the inexperienced Sophia to Parisian high society, the couple returned to Athens on the 19th of February 1870, ready to divorce. Sophia's letters to her family from Paris mention the couple's busy social life, but reading between the lines it is clear that on the one hand Sophia was unable to respond to her husband's excessive demands, and on the other that she was bitterly homesick for Greece and her family. On arriving in Greece, Heinrich was confronted by Sophia's mother and elder brother, who accused him of not having presented his wife with a single jewel of any value.

Dreading the scandal of a divorce, and with Schliemann having already left for Troy for the preliminary trial trenches, Sophia's family lowered the tone of their confrontation. Since the Ottoman authorities had not granted him formal permission to excavate Troy, Heinrich soon returned to Athens.

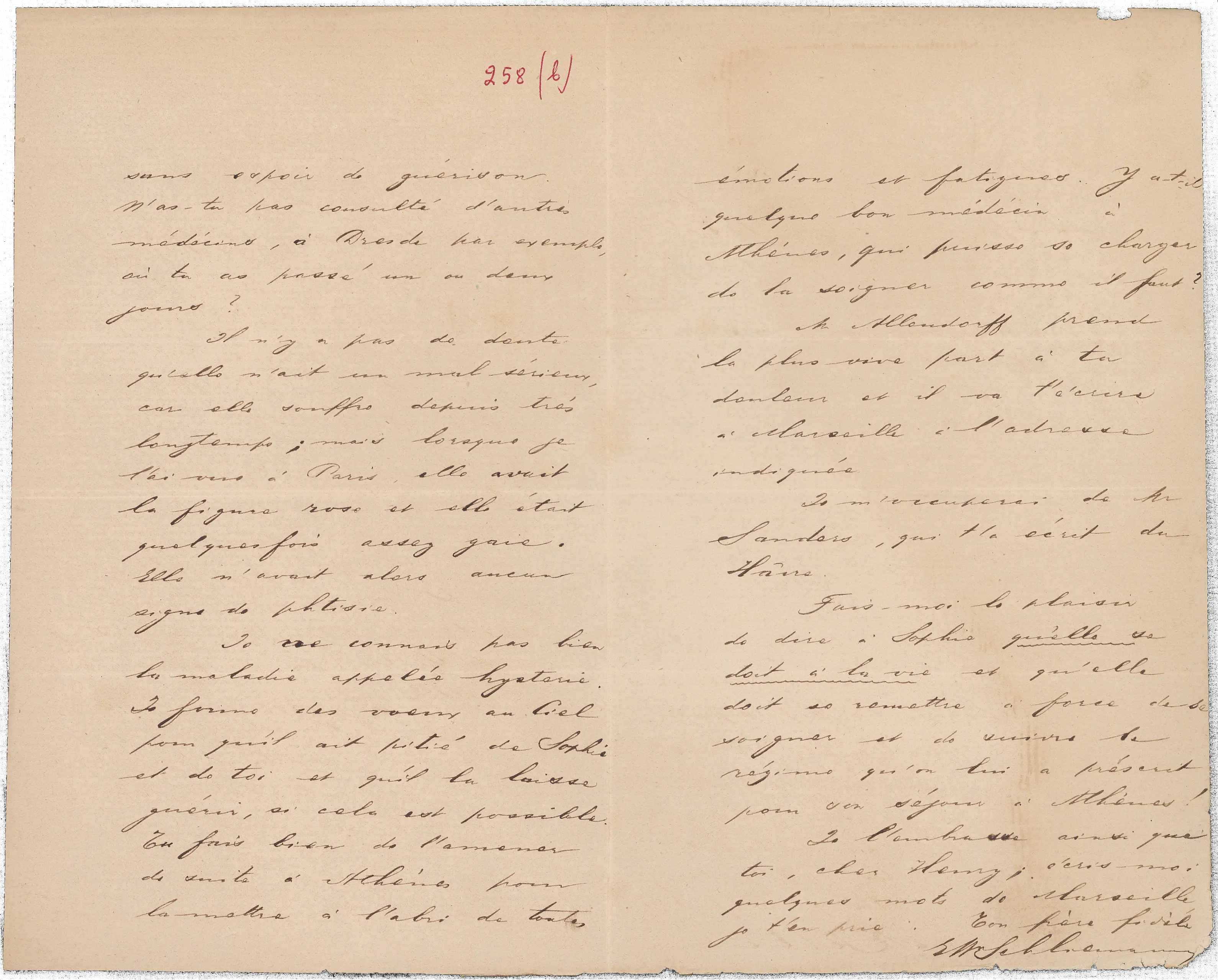

In the belief that his young wife was ill, he took her on another journey to Europe, to the Schweizermühle sanatorium in Germany. There Sophia was diagnosed with 'hysteria', a favourite medical diagnosis at the time for women who had difficulty adjusting to the demands of married life.

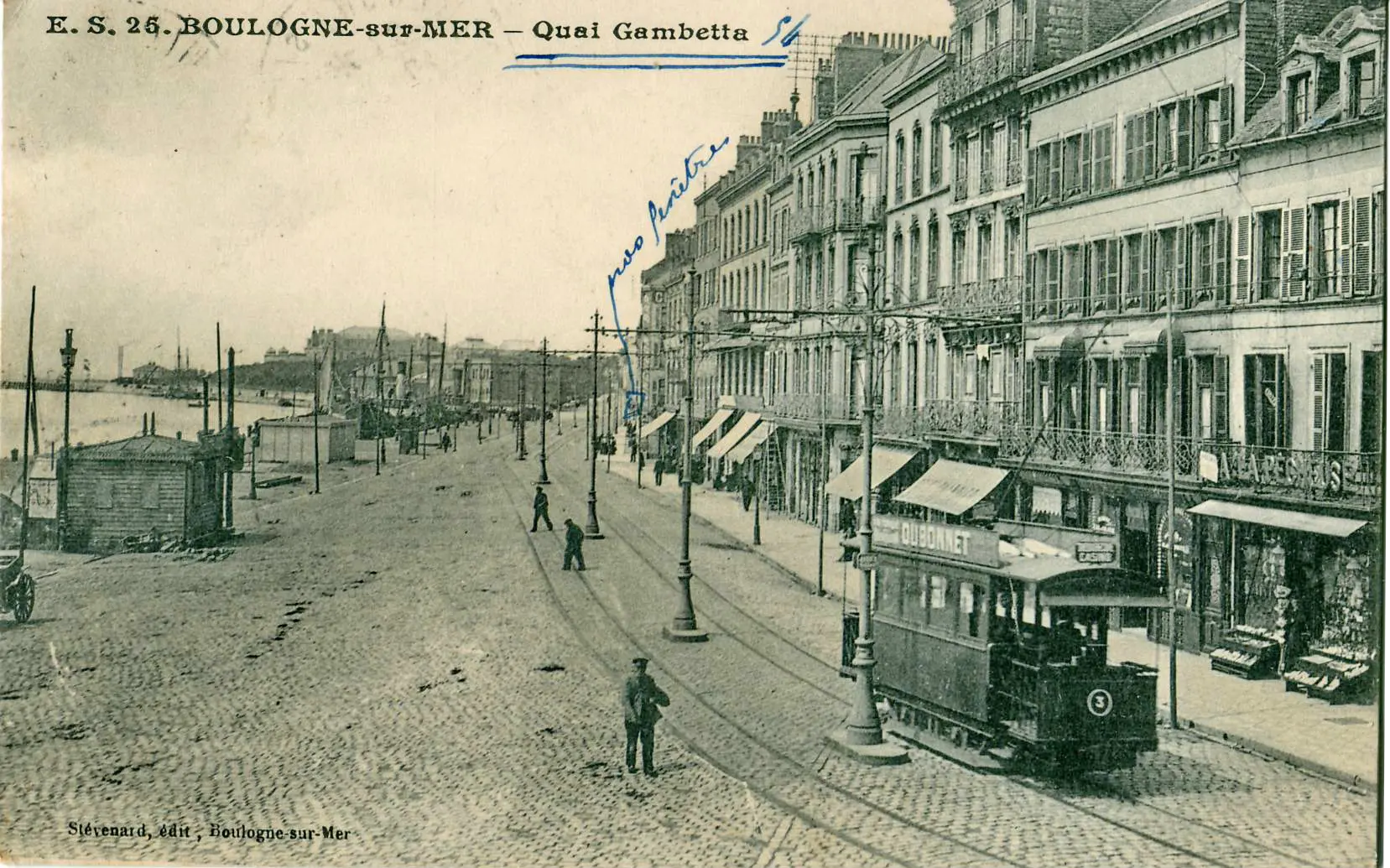

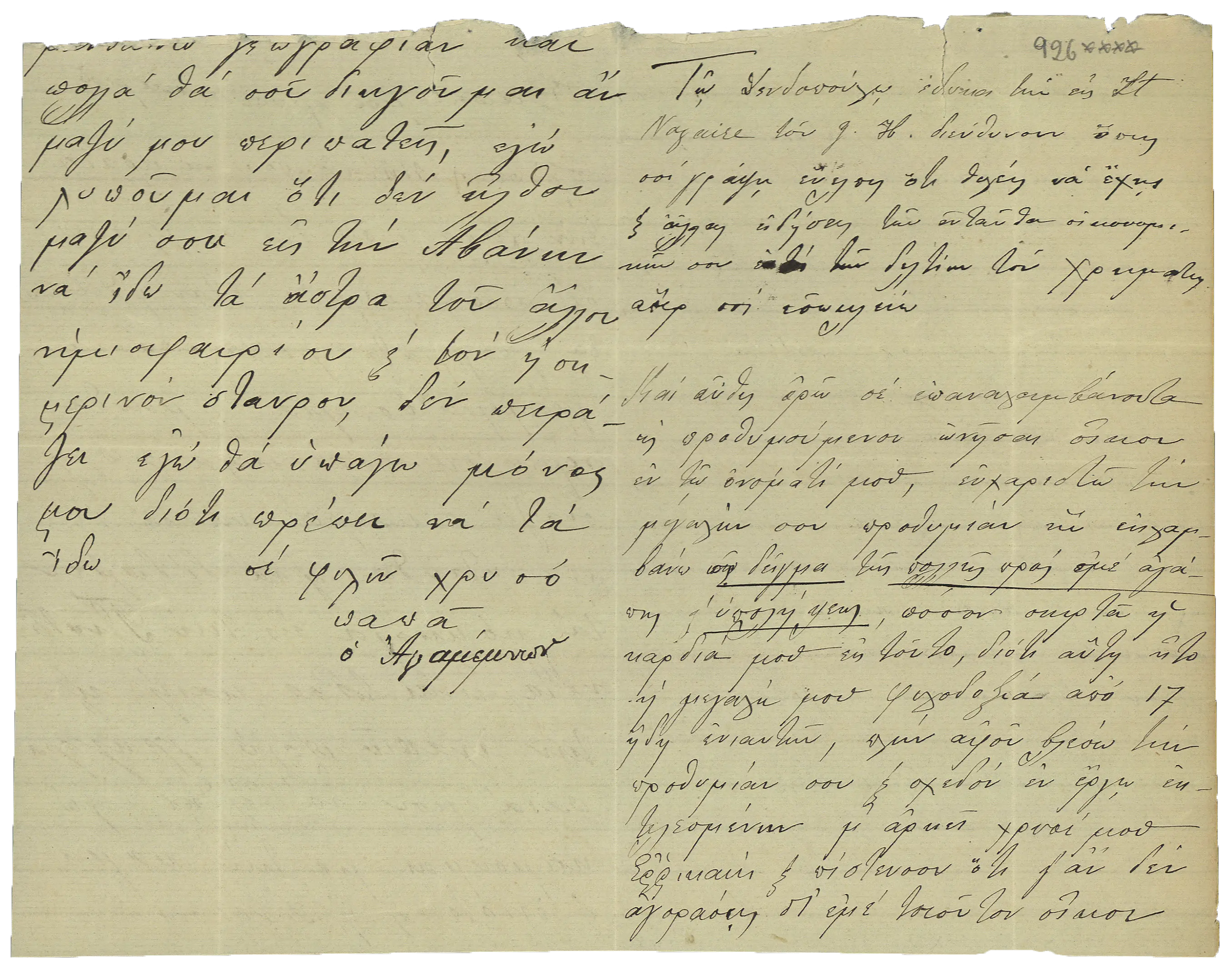

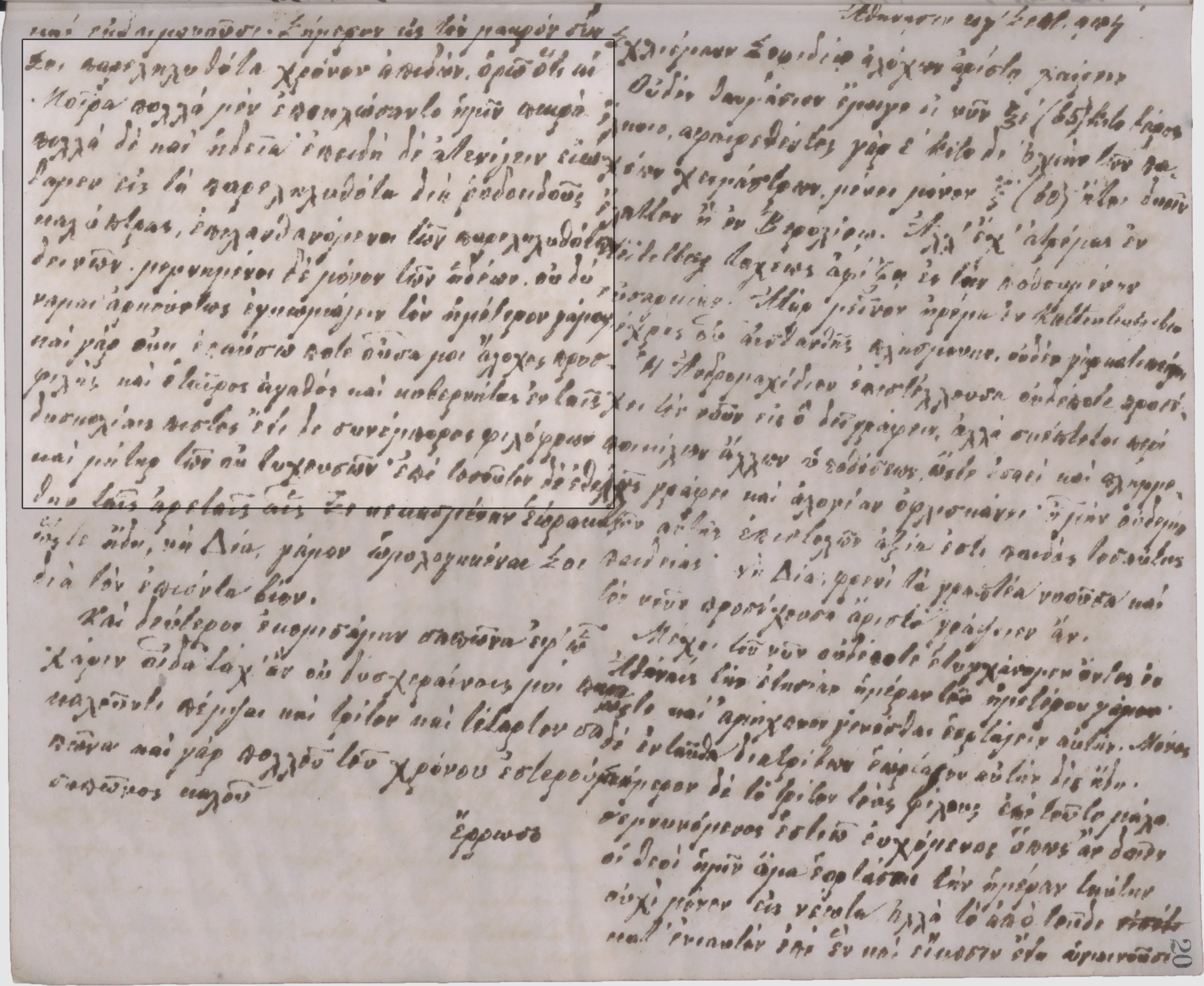

The couple returned to Athens on the 2nd June 1870, and Schliemann was due to embark for France the next day. In a letter that he gave Sophia when they landed, but which he had written on board, he represented himself as the victim of the marriage and Sophia as the bad wife, a victim of her family's decisions. However, what we glean from a reading of the letter is that Heinrich felt uncomfortable in the face of the unexpected disobedience and the emergent powerful personality of his young wife.

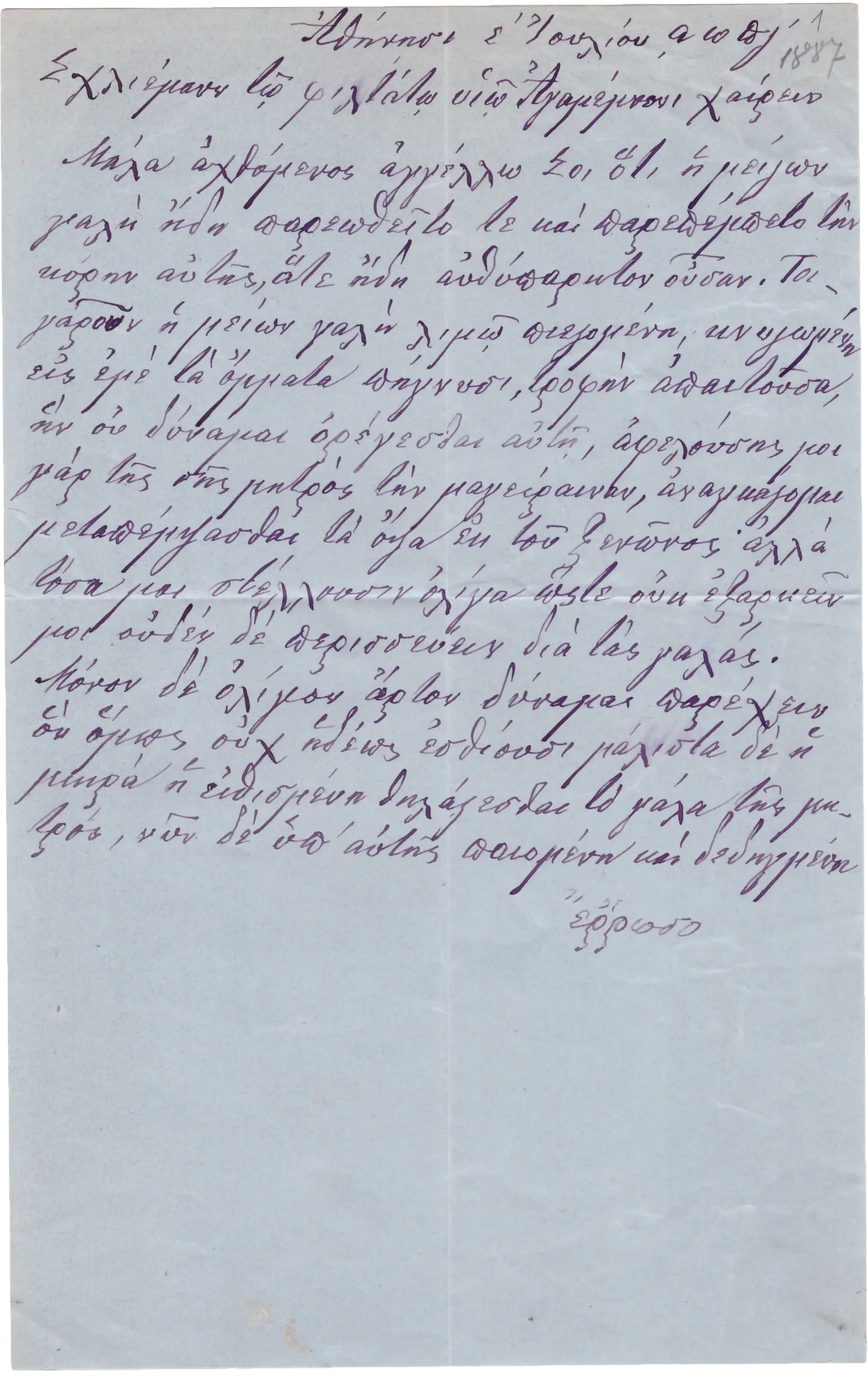

2. MEDICAL ADVICE

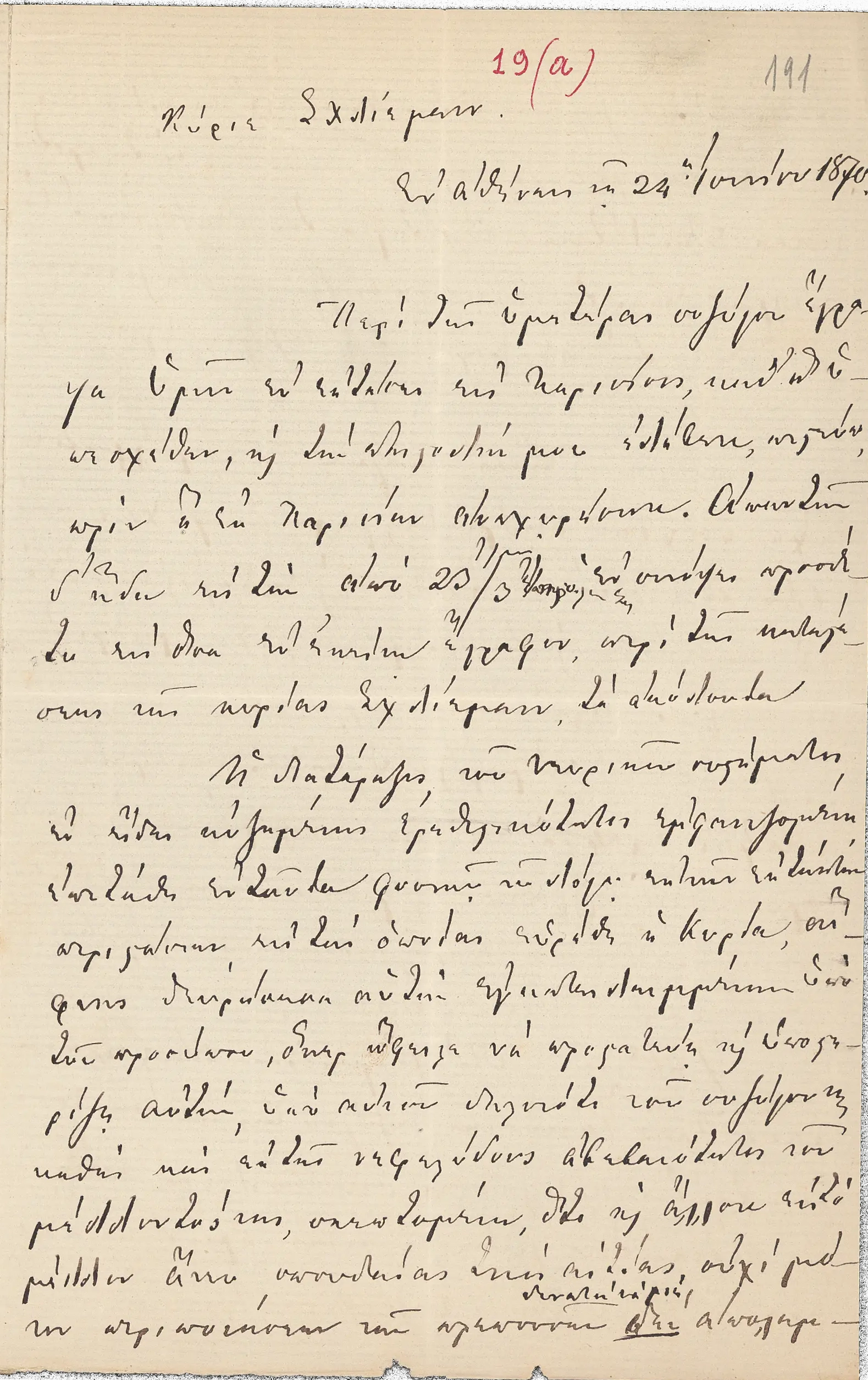

The doctor Miltiadis Venizelos (1822-1887), who was the same age as Schliemann and in charge of the mentally and physically distraught Sophia, in two letters written on the 22nd and 23rd June 1870 tried to persuade Schliemann to abandon the idea of divorce. For one thing, a second divorce would irrevocably damage his reputation, and for another he was in large part responsible for the situation, as he should have foreseen that marriage to such a young girl would not be easy. Thus, it was not Sophia alone who was to blame, and who according to Venizelos was a woman 'with a good heart, a healthy mind and a high spirit'. Contrary to the diagnosis of the German doctor at the Schweizermühle sanatorium, the Greek physician did not attribute Sophia's behaviour to hysteria. Schliemann should show greater patience and try harder to make Sophia happy, the implication being that many problems would be solved if she got pregnant.

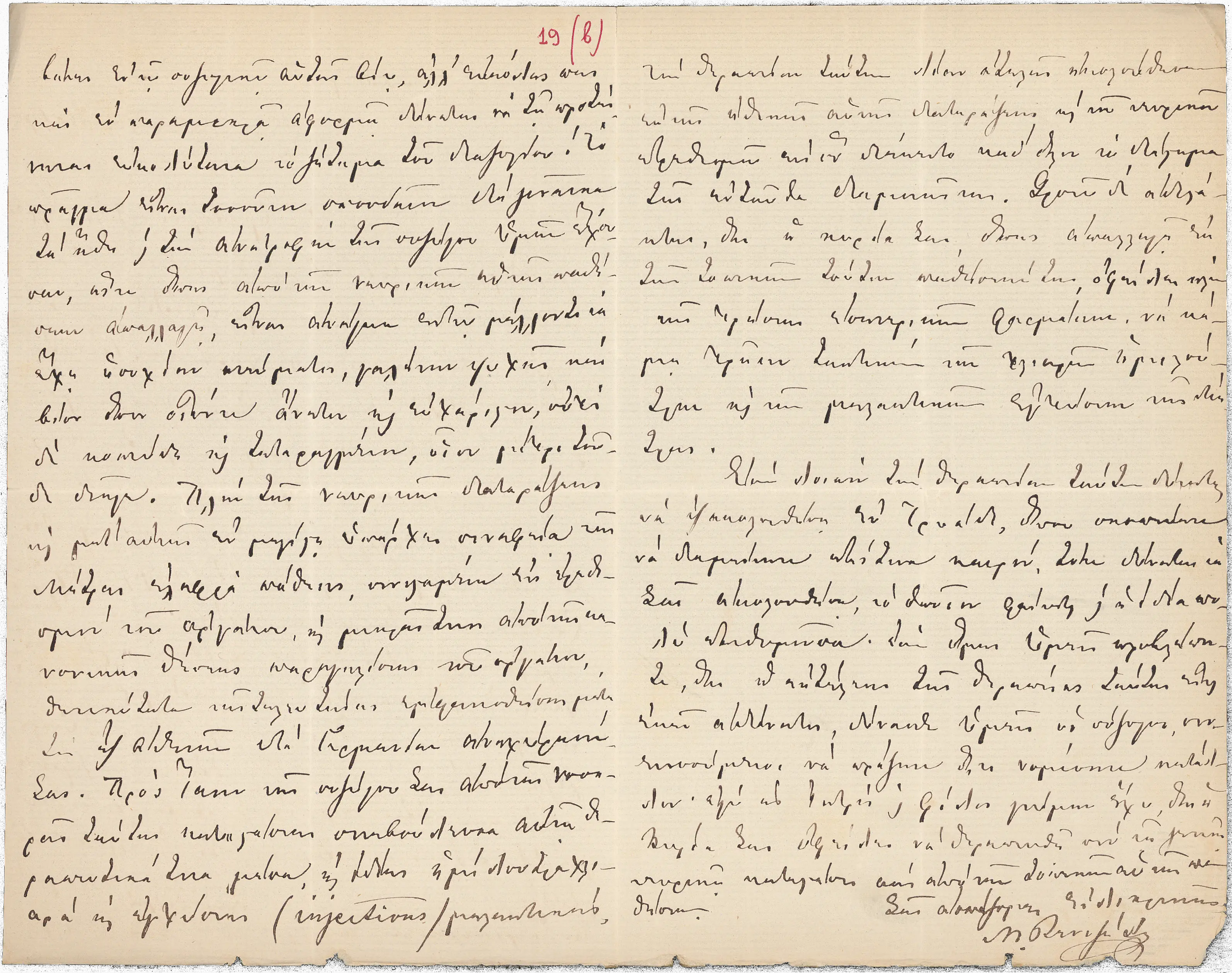

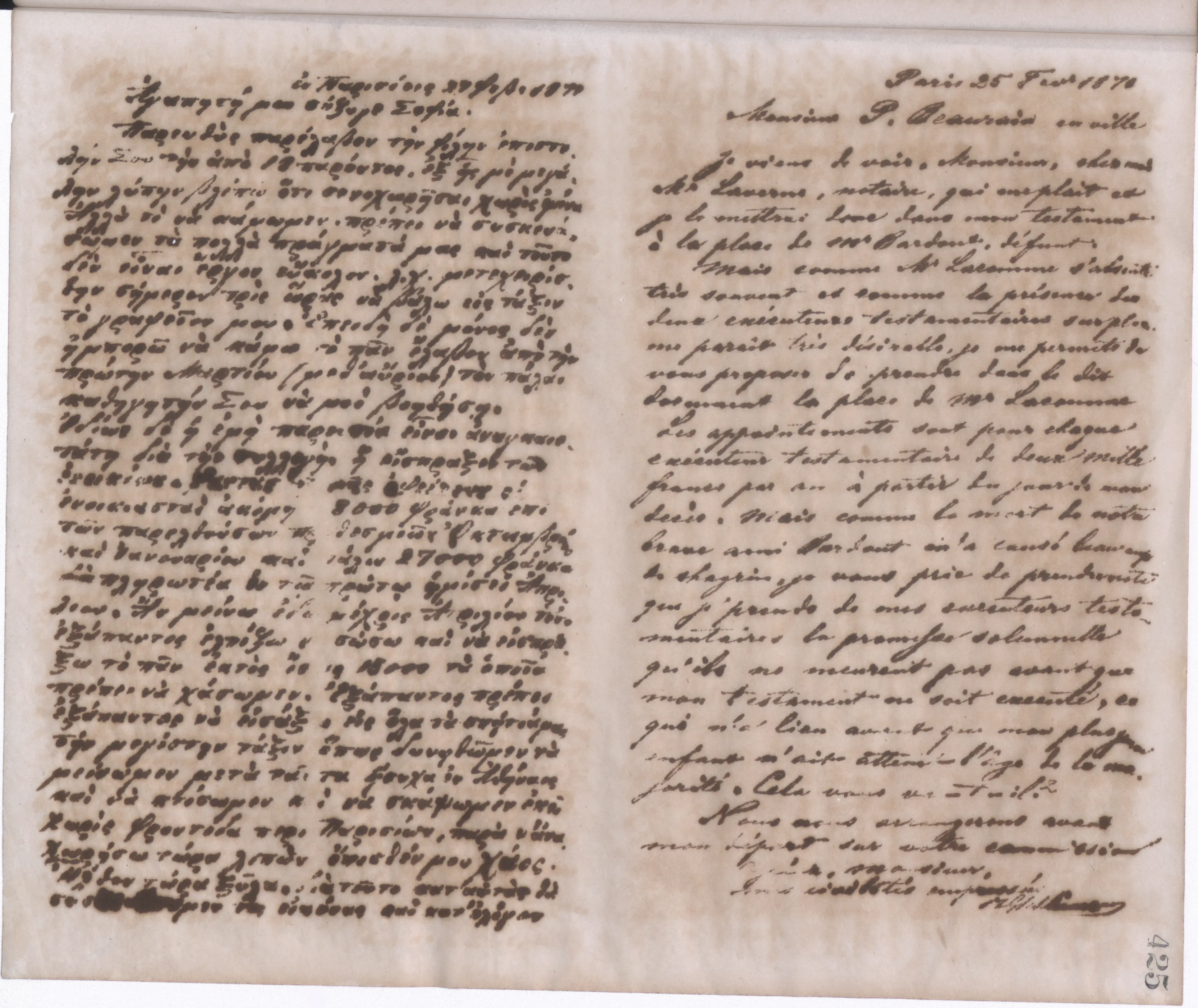

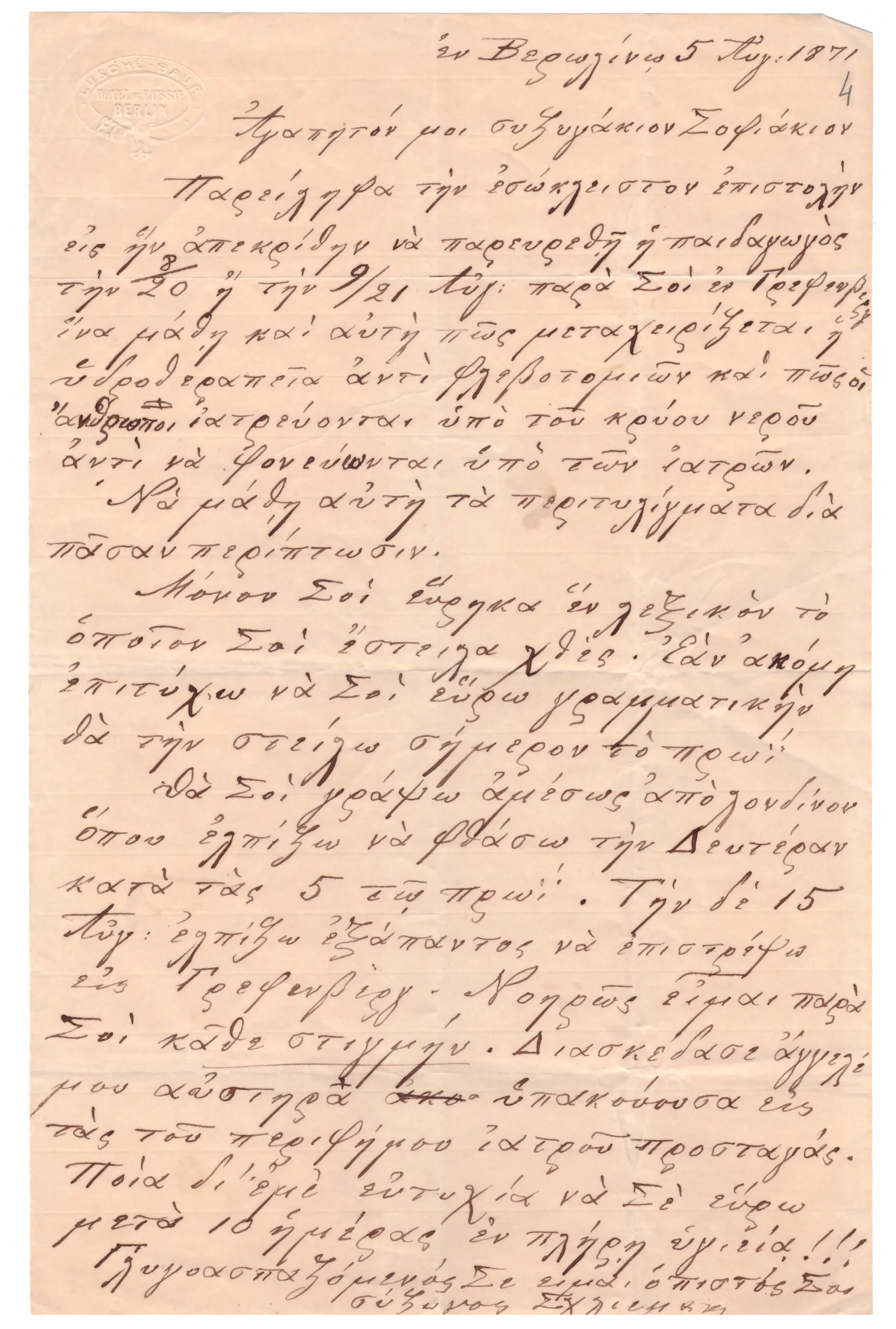

Schliemann followed the Greek doctor's advice, with positive results. Danae Koulmasi (Schliemann and Sophia: a love story, Athens 2006, pp.64-65) believes that the change in Schliemann's behaviour had another more fundamental cause. Schliemann 'wanted to keep the dream alive...he still saw Sophia as an inalienable part of his life and work'. In July 1870 Heinrich and Sophia went to Paris and thence to the north coast of France, where they spent August in Boulogne-sur-Mer, and Sophia relaxed beside the sea she adored. During the months that followed, Schliemann, who was again away on his business travels, was transformed into an affectionate husband, sending her loving letters with words of advice and caution: Sophia was pregnant.

Nine months later, on the 25th April 1871, their first child Andromache was born. Heinrich and Sophia would find refuge in peaceful Boulogne-sur-Mer many times in the course of their twenty years of marriage. In the summer of 1877, the successful appearance of the Schliemann couple at the Royal Institute of Archaeology in London was followed by six weeks of holiday at Boulogne-sur-Mer. A few months later, on the 16th March 1878, Sophia gave birth to their second child, Agamemnon.

Poikili Stoa magazine, Ethnikon Imerologion 1889.

3. ERRIKAKI AND SOPHIAKION

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Curtis Runnels Papers.

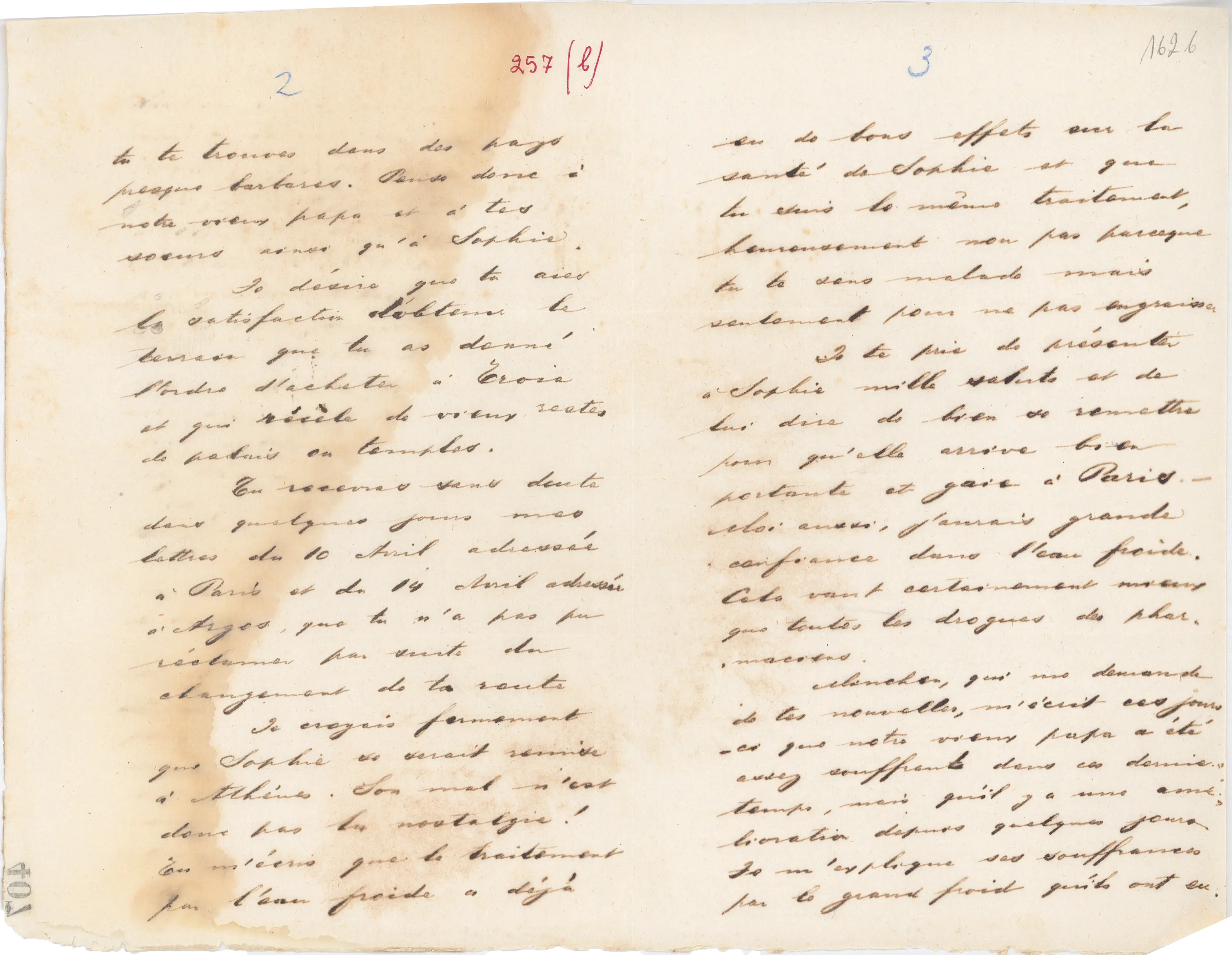

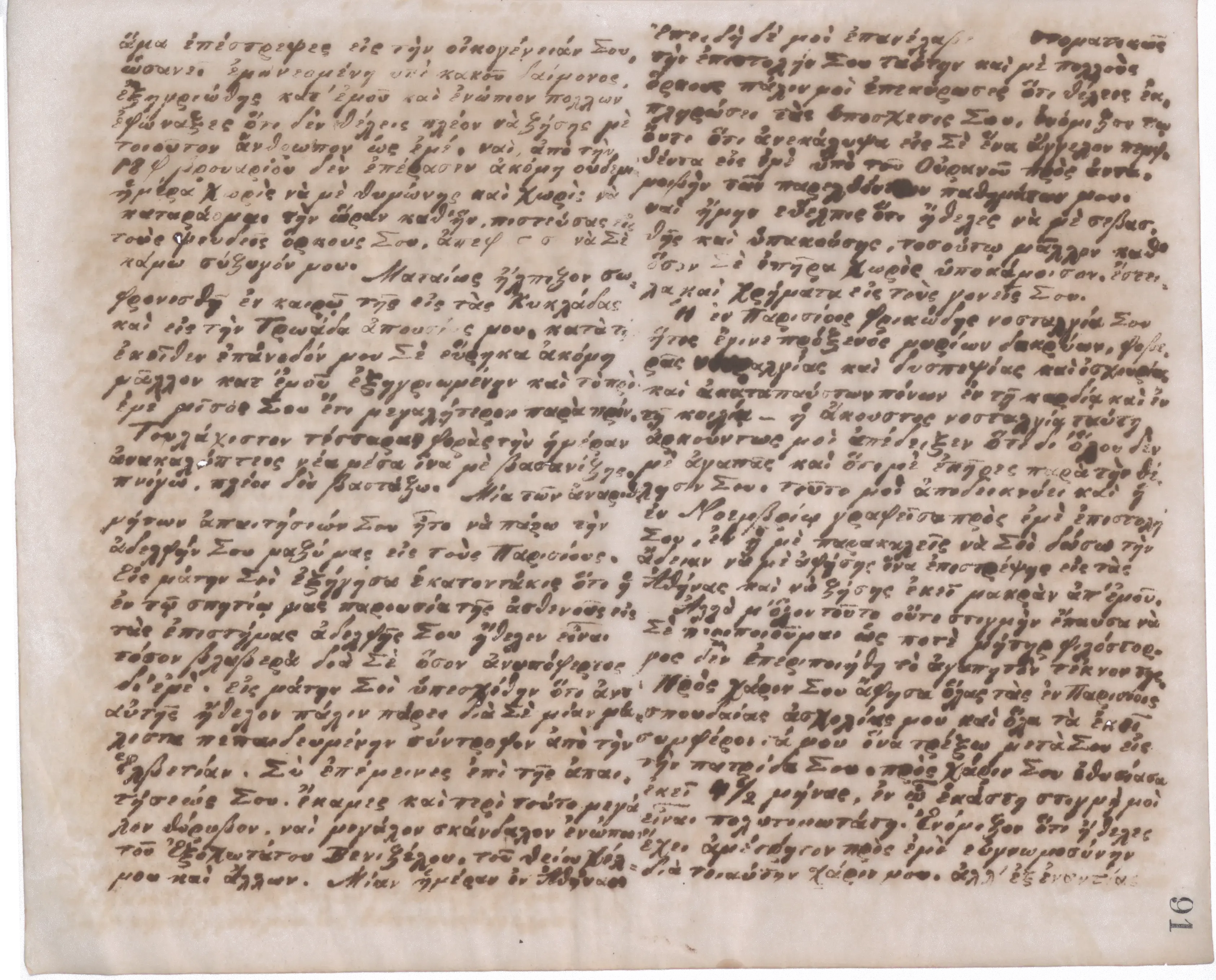

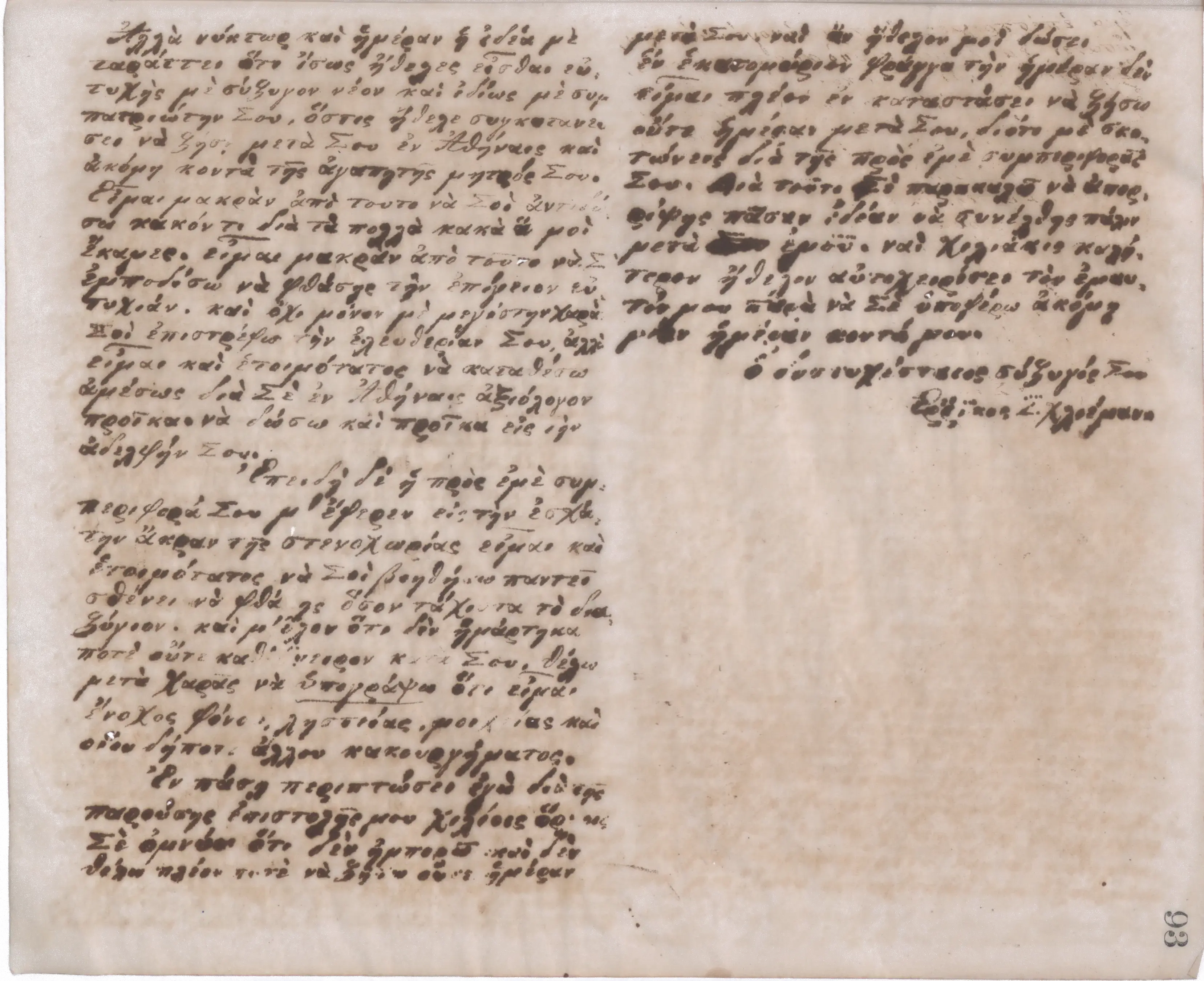

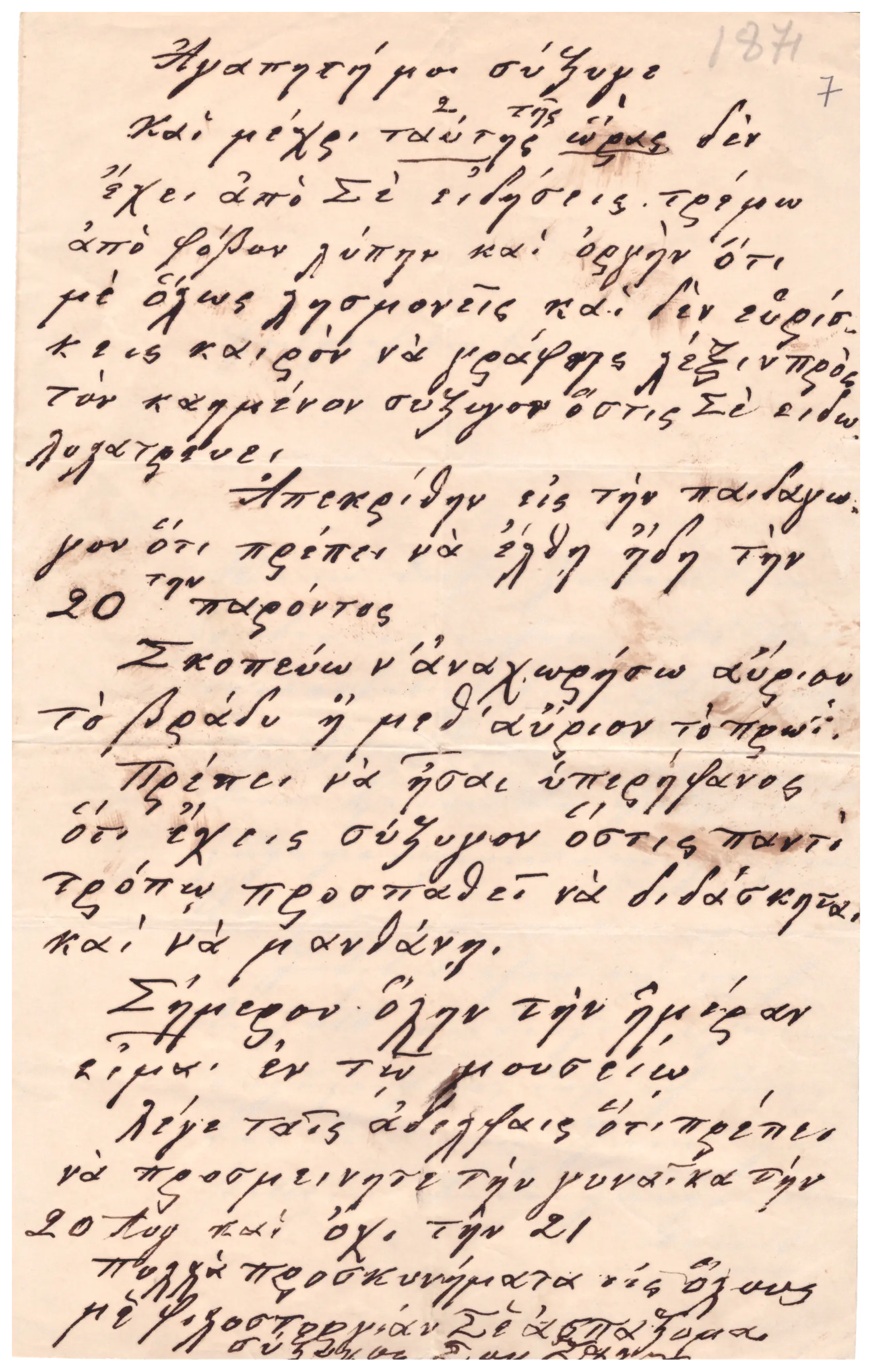

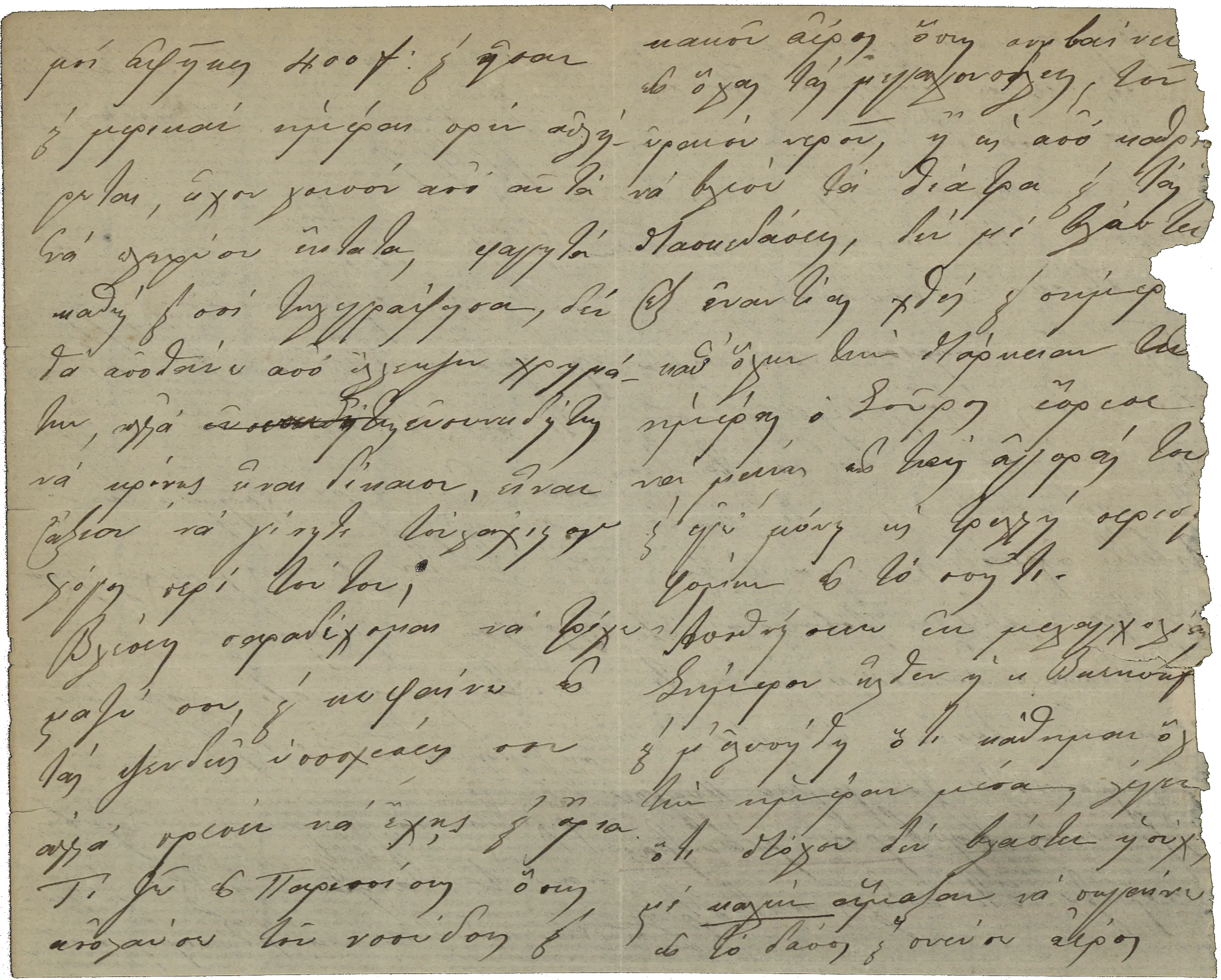

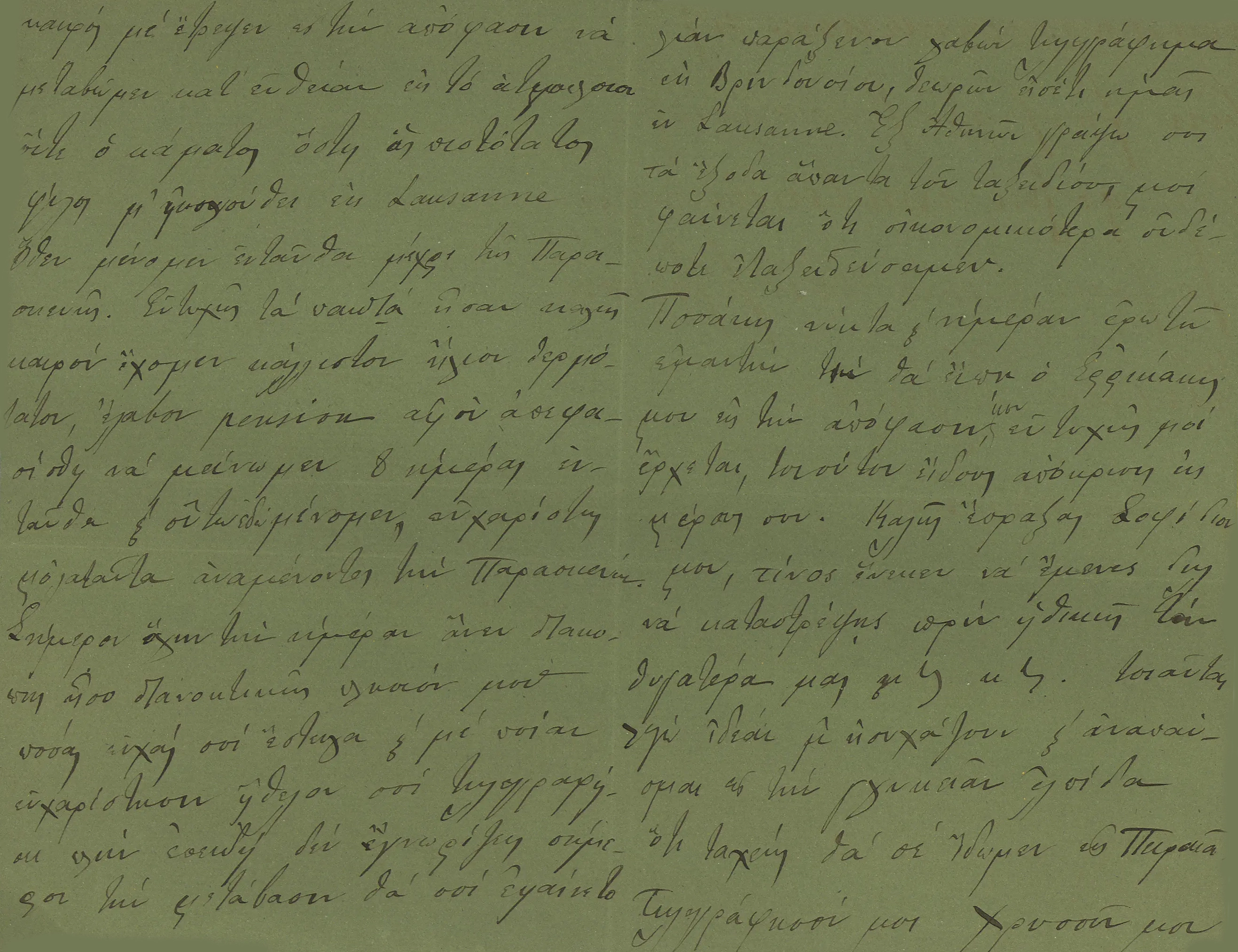

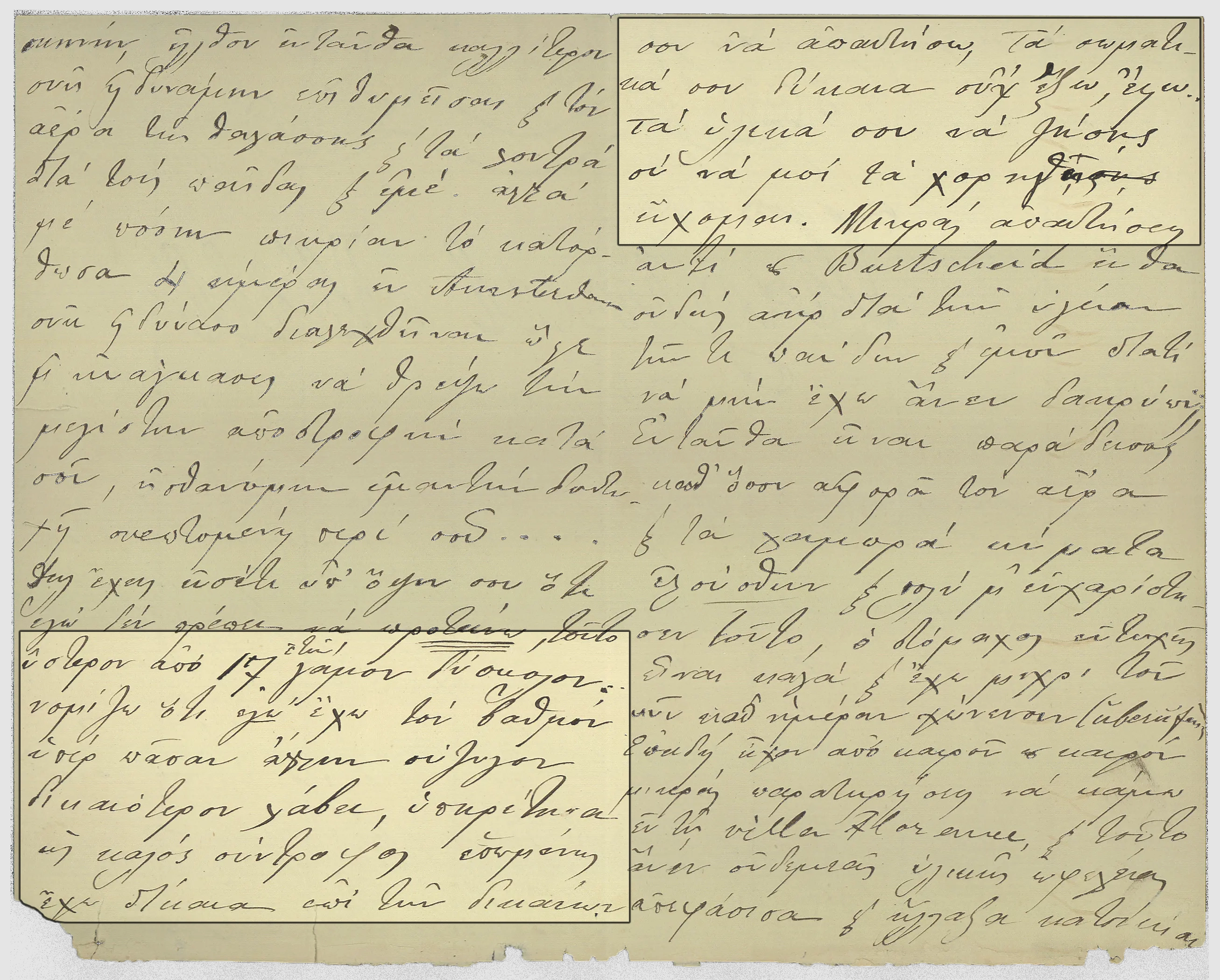

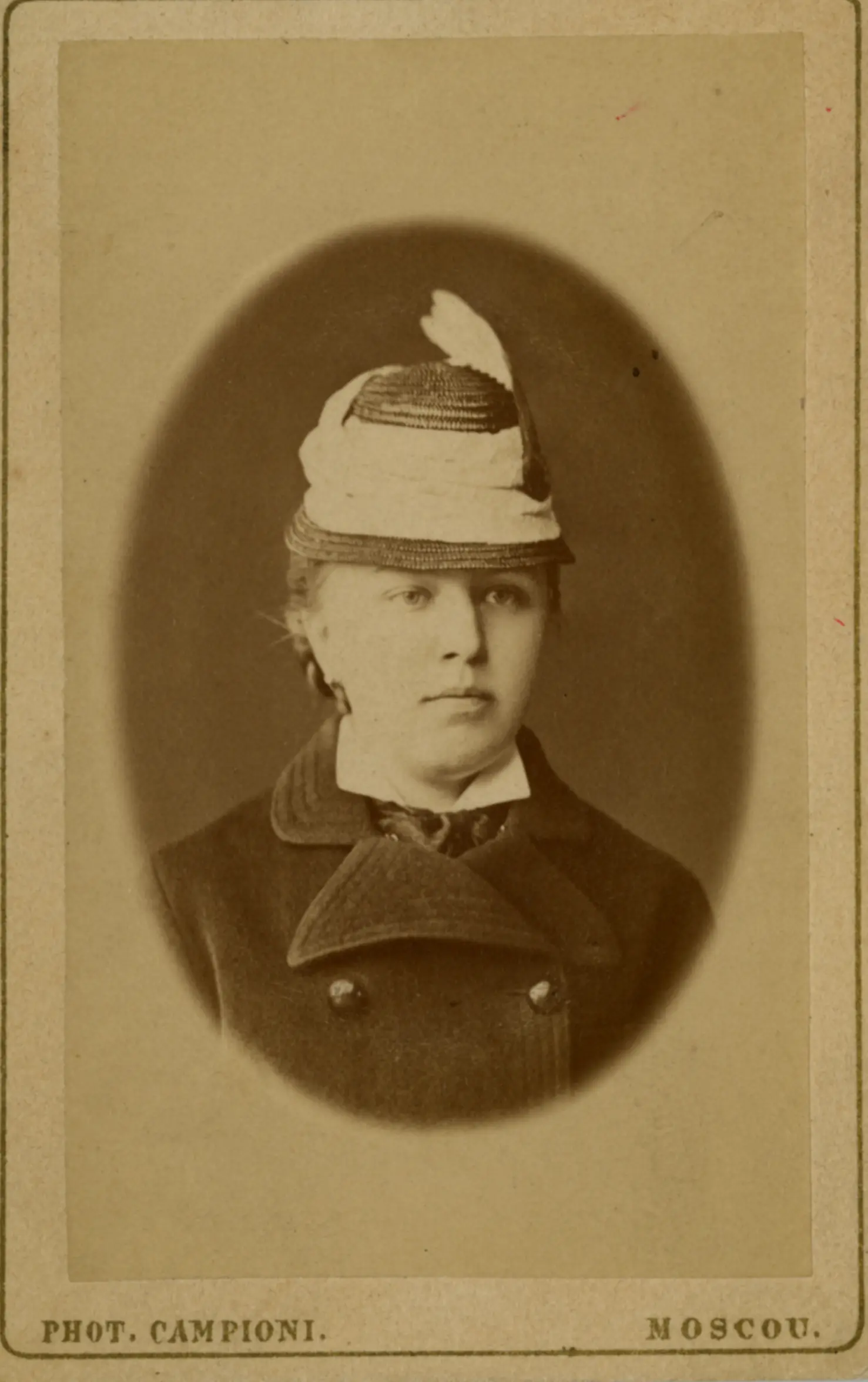

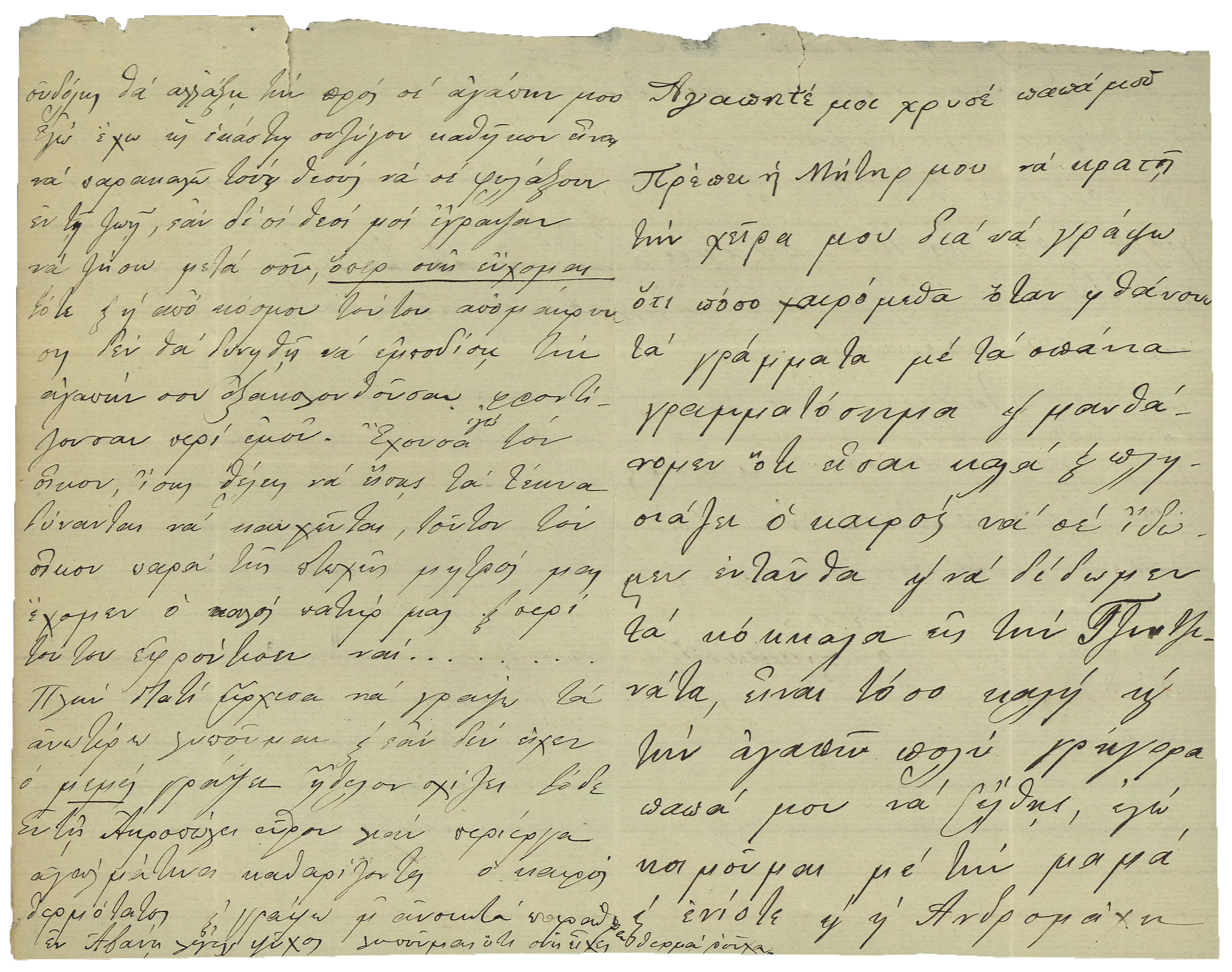

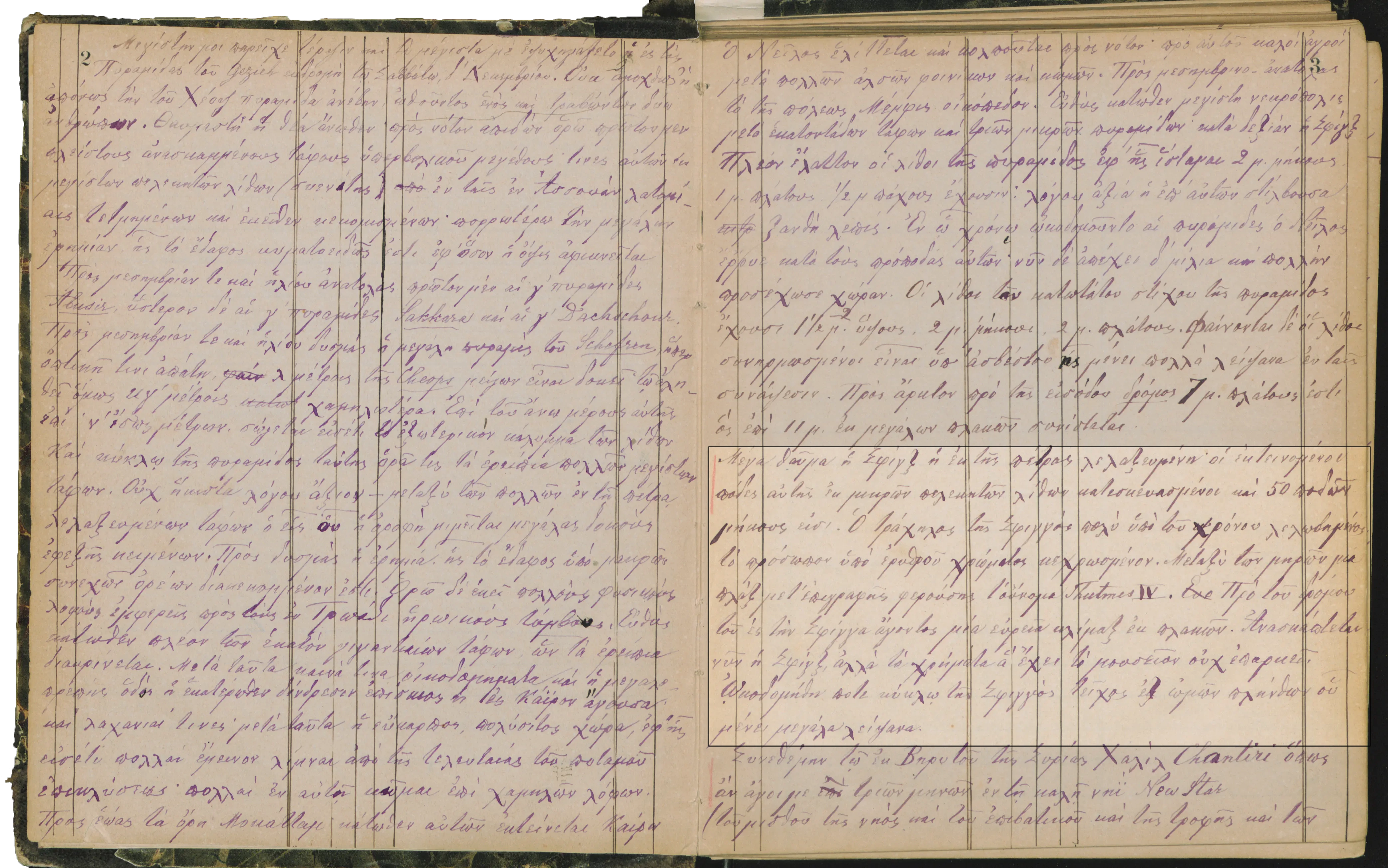

Sophia and Heinrich exchanged hundreds of letters in the course of their twenty-one years of marriage, far more than most couples at the time. Heinrich's frequent and lengthy absences from the family roof, whether for excavations or for other reasons, and the obligatory summer breaks for Sophia, usually without Heinrich, in various European thermal baths, were the main reasons for such frequent correspondence..

Most of Sophia's letters to Heinrich have been published by Eleni Bombou-Protopappa (Letters to Heinrich, Athens 2005). Heinrich's letters to Sophia have not been published separately. Danae Koulmasi in her book Schliemann and Sophia: a love story (Athens 2006) quotes extracts from his letters, but as they are not referenced it is very difficult to locate them in the archive.

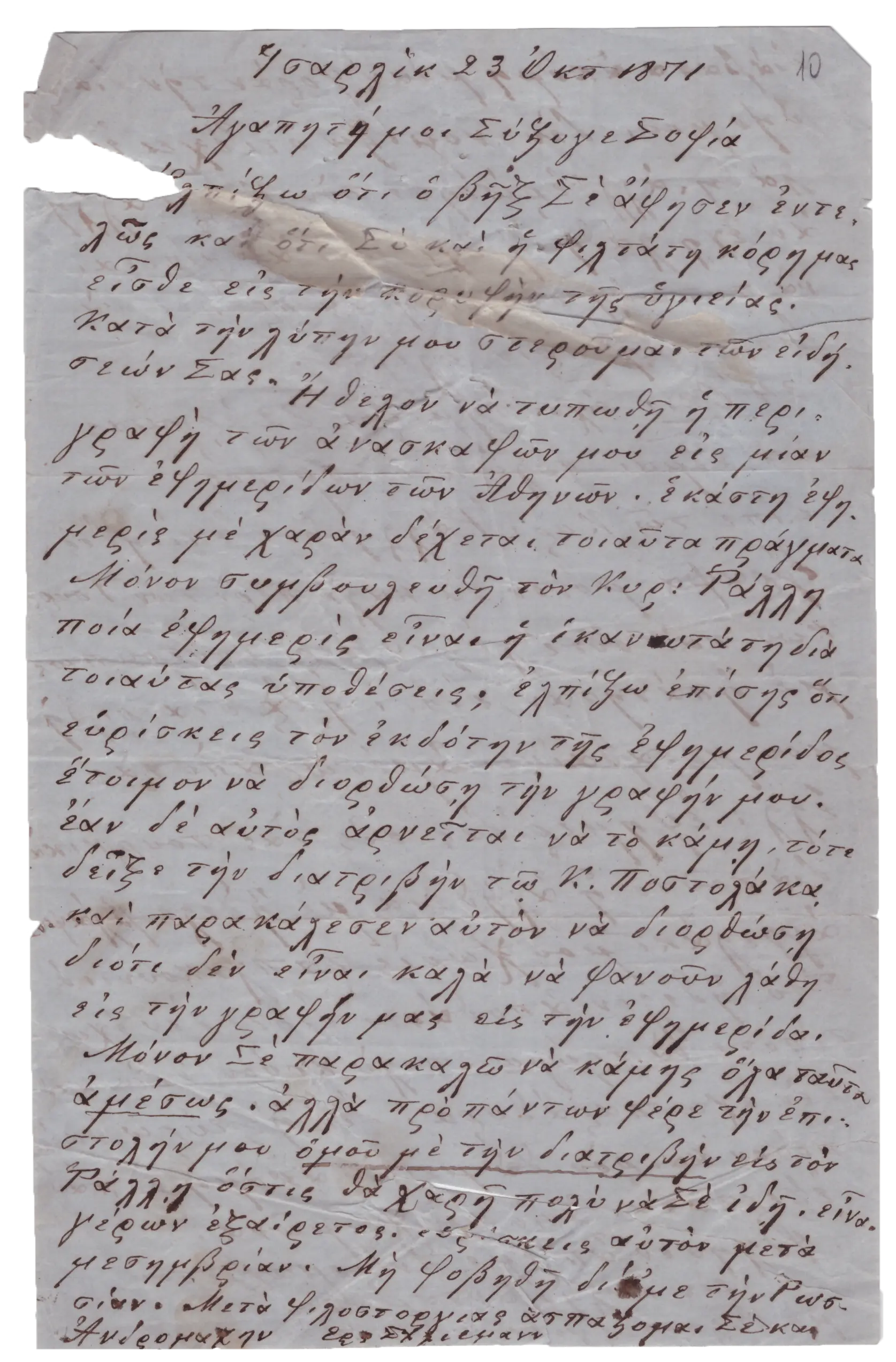

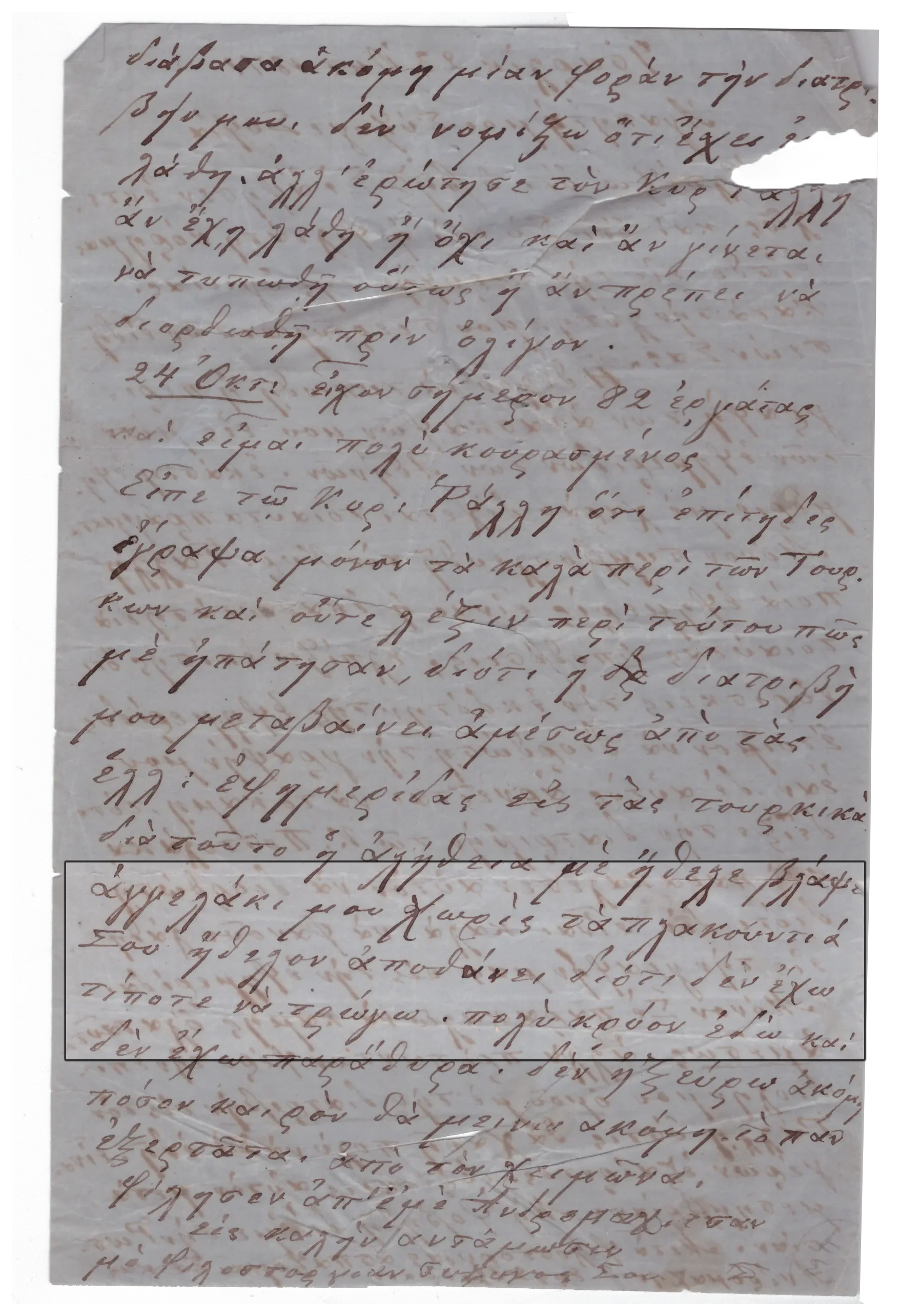

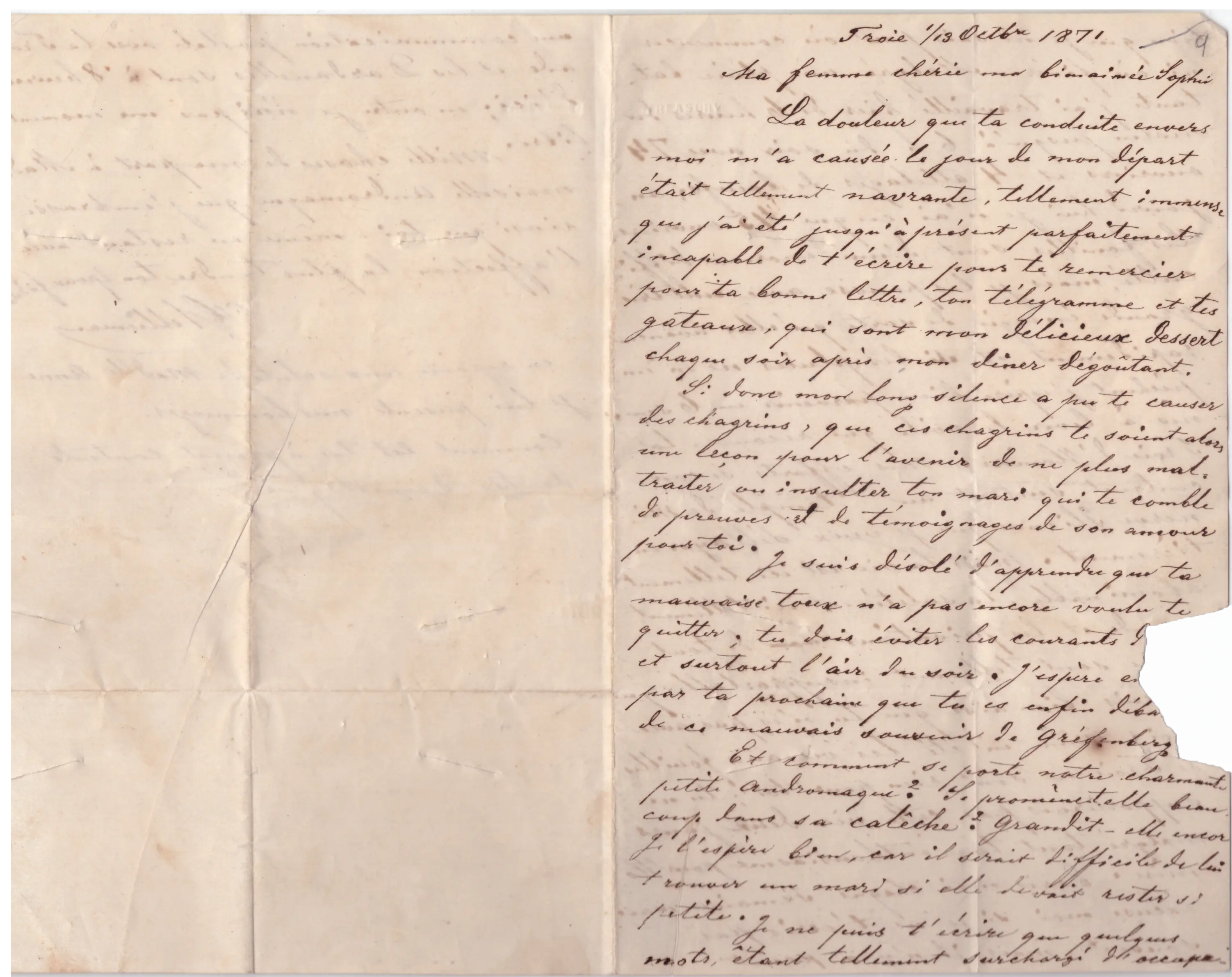

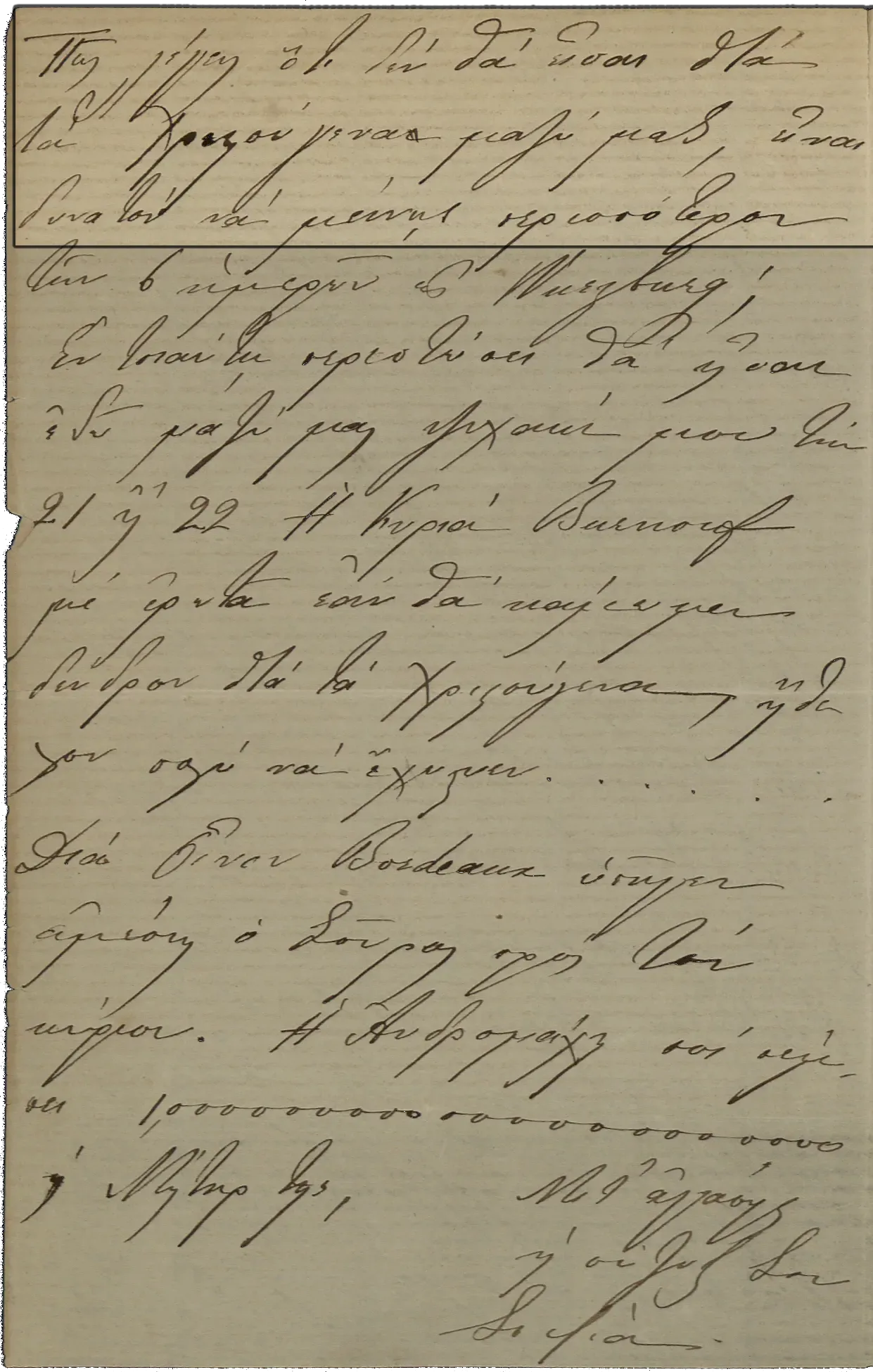

After the turmoil of their first months of marriage, their trip to Boulogne-sur-Mer in August 1870, Sophia's pregnancy and the birth of Andromache in April 1871, we observe a striking improvement in the couple's relationship. In the Sophia Schliemann Papers are preserved ten letters from Heinrich, sent during a 6-month period between August and December 1871.

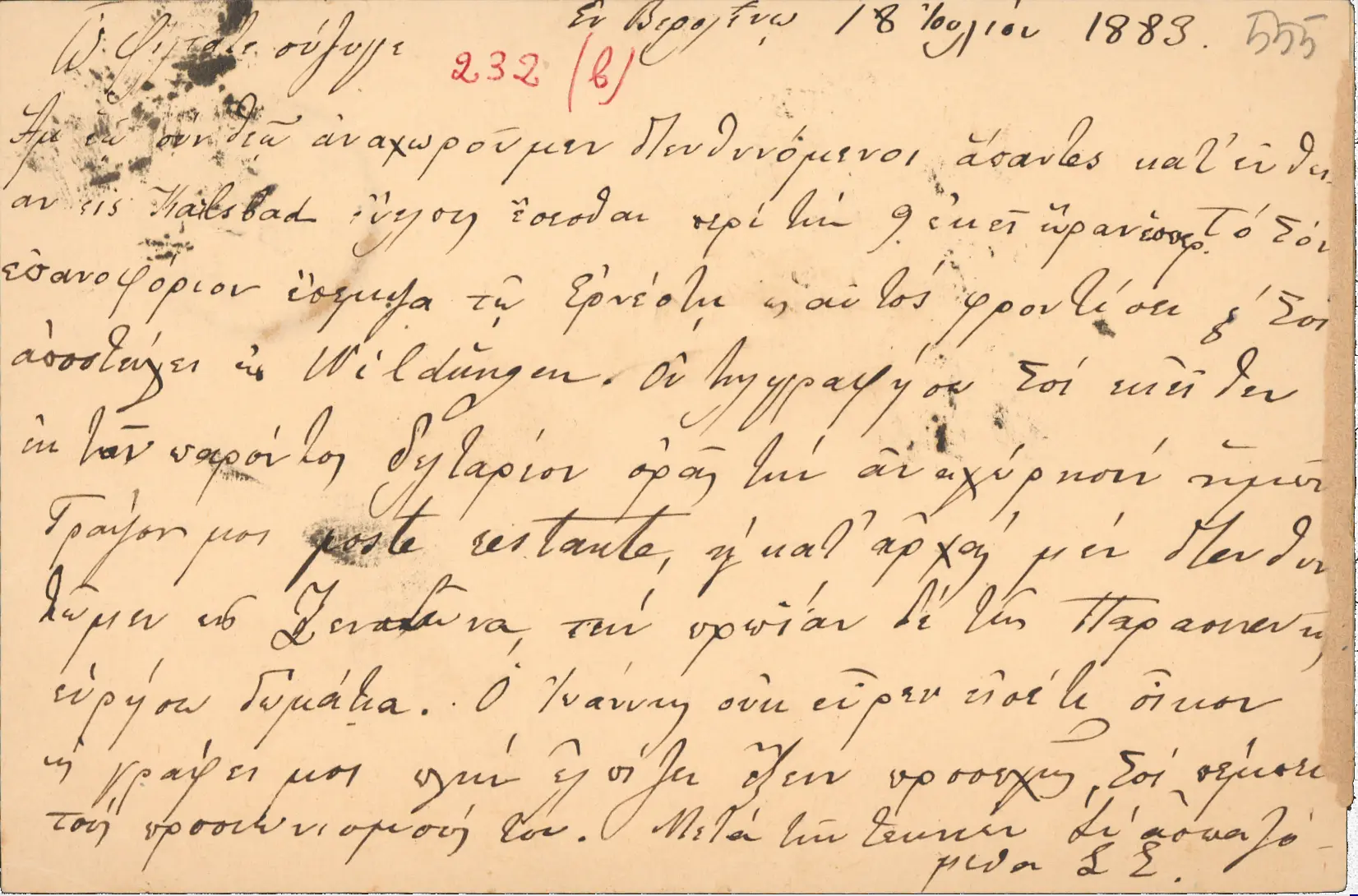

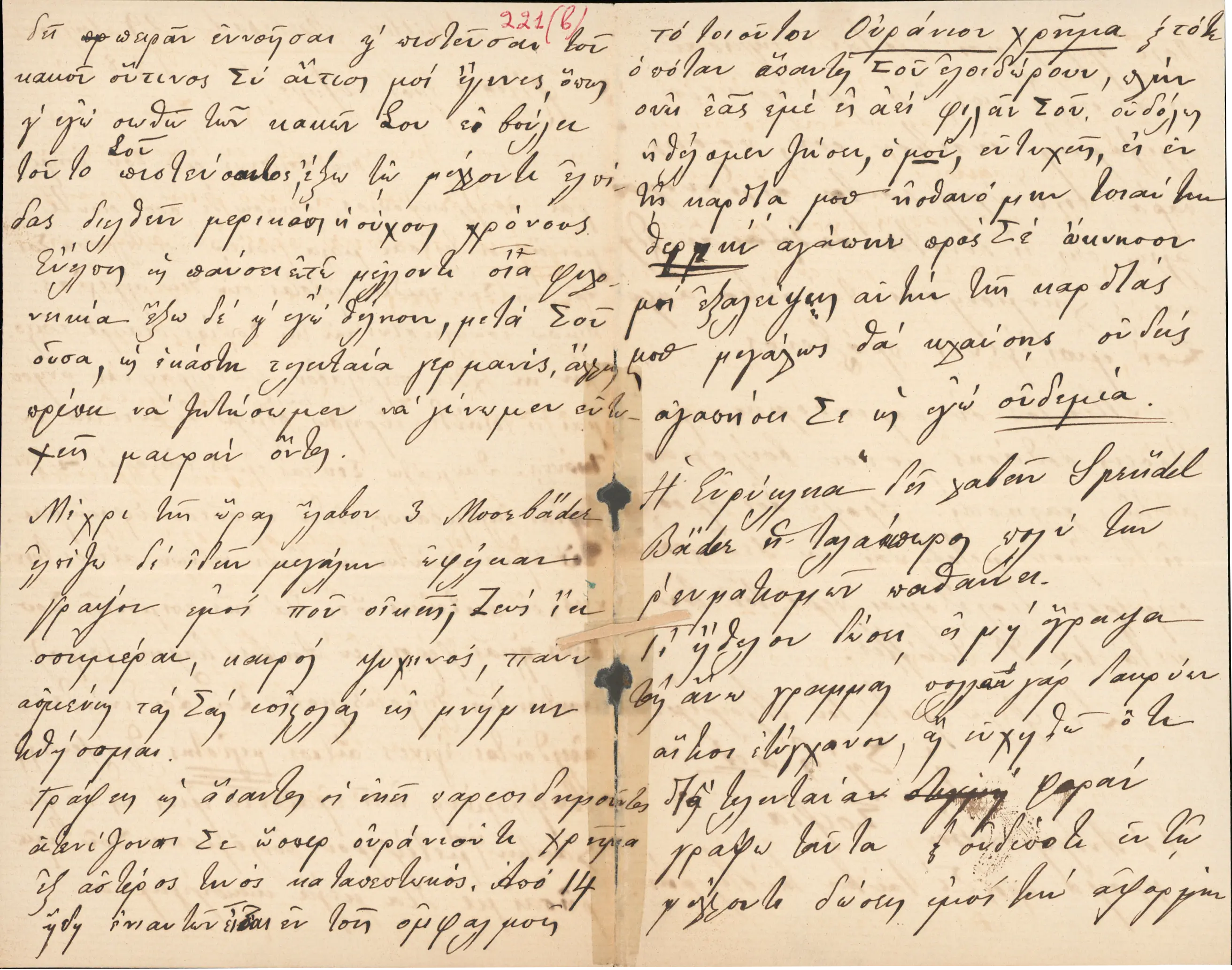

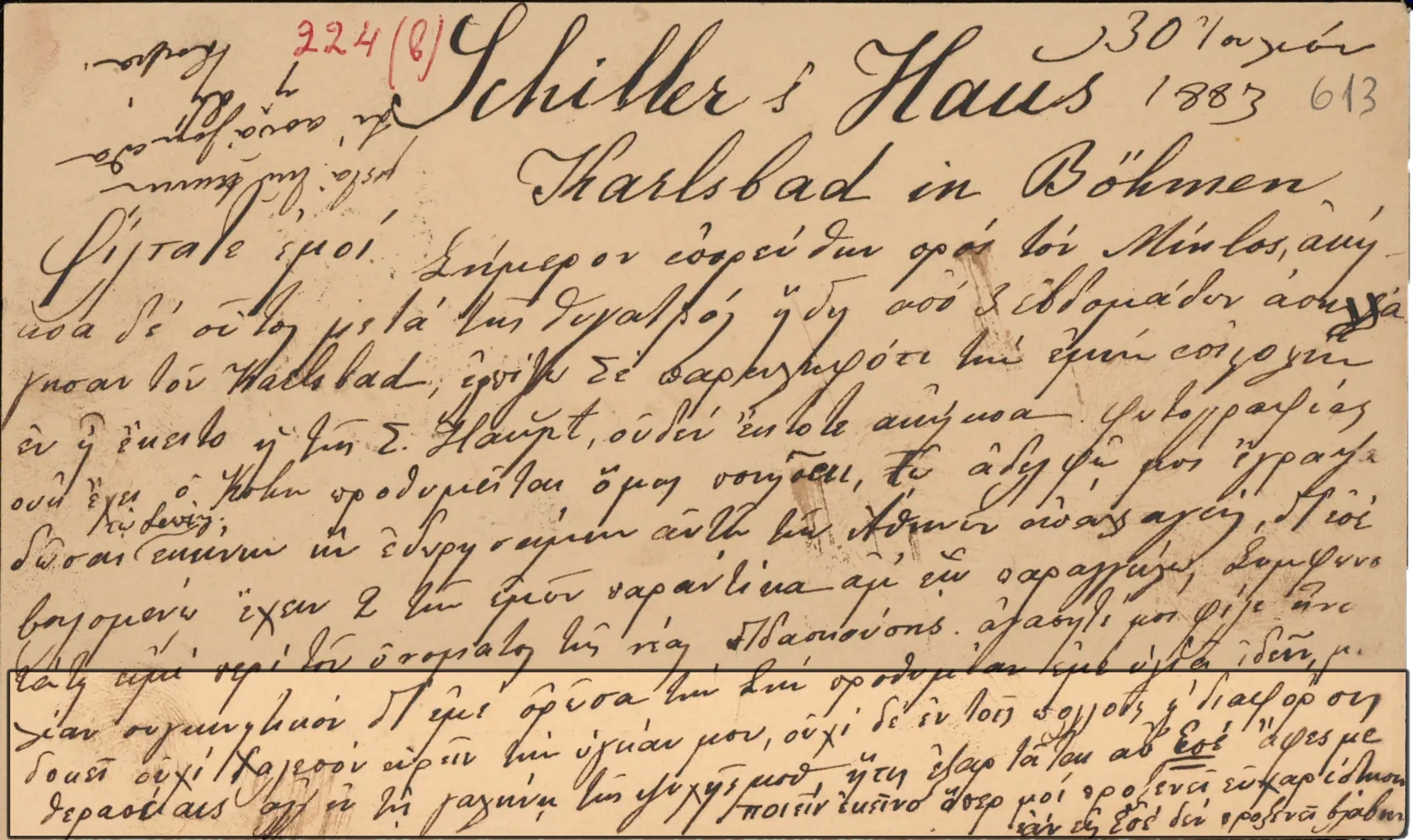

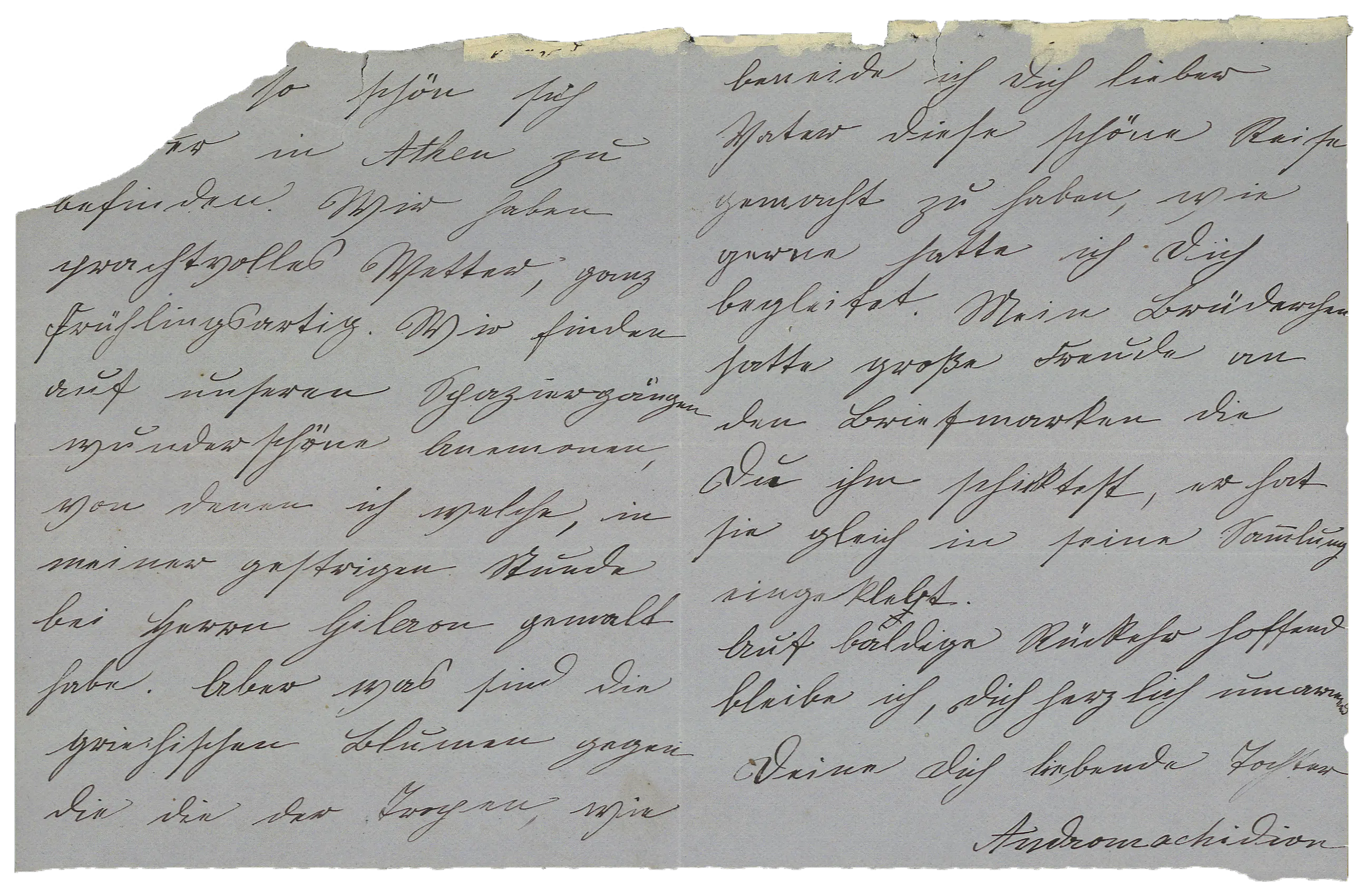

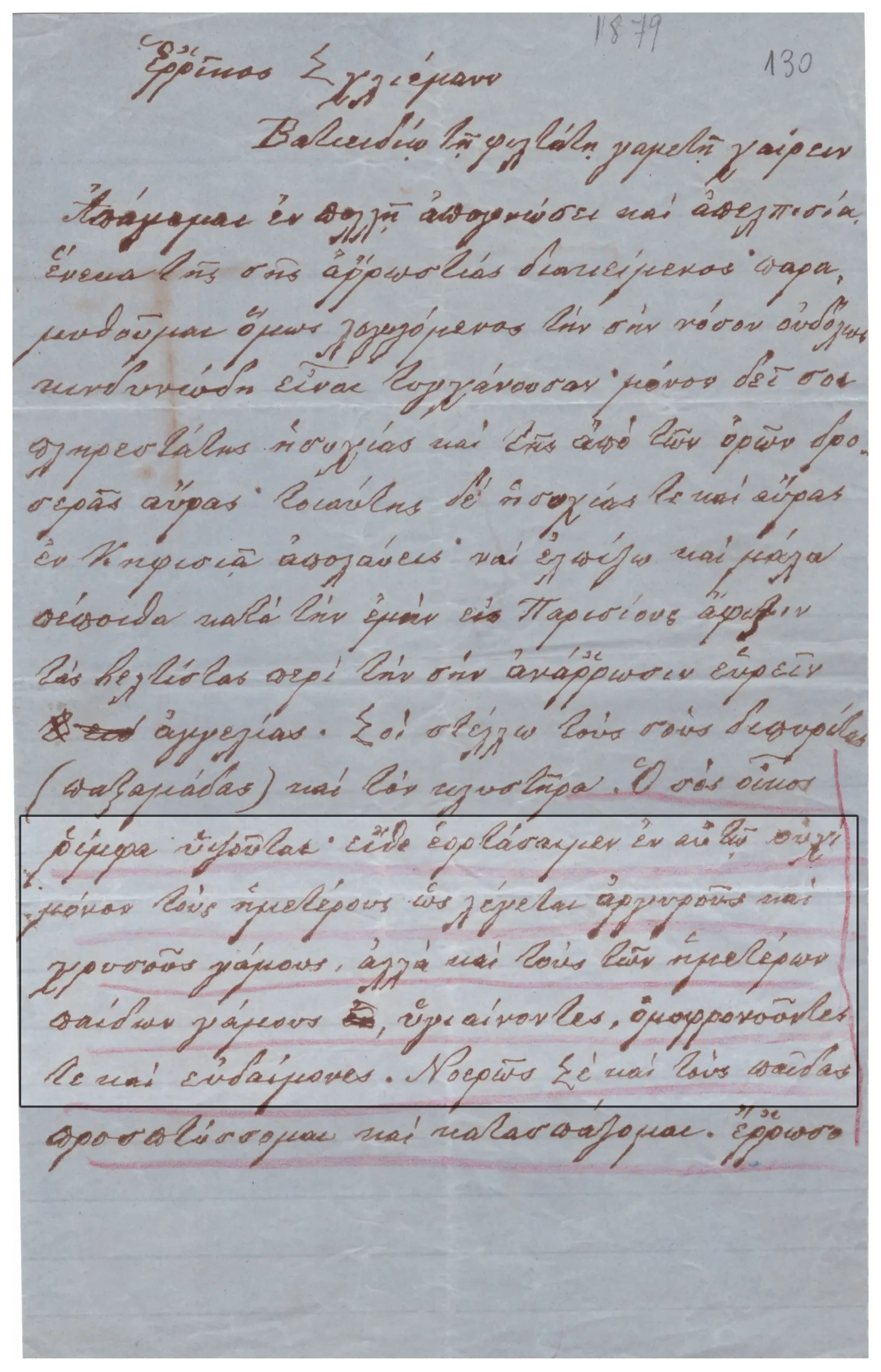

Sophia is a little more conventional in her expressions: 'My dear and much-loved husband' on the 25th April 1872, the day of Andromache's first birthday when Schliemann was away at Troy, and also 'My dear husband Errikaki' (28th September 1875), 'My beloved Errikaki' (4th October 1875), a time when their relations were again strained. She usually ends her letters either with her name and surname, or 'with love from Your faithful wife Sophia' or 'The children and I embrace You' (18th July 1883).

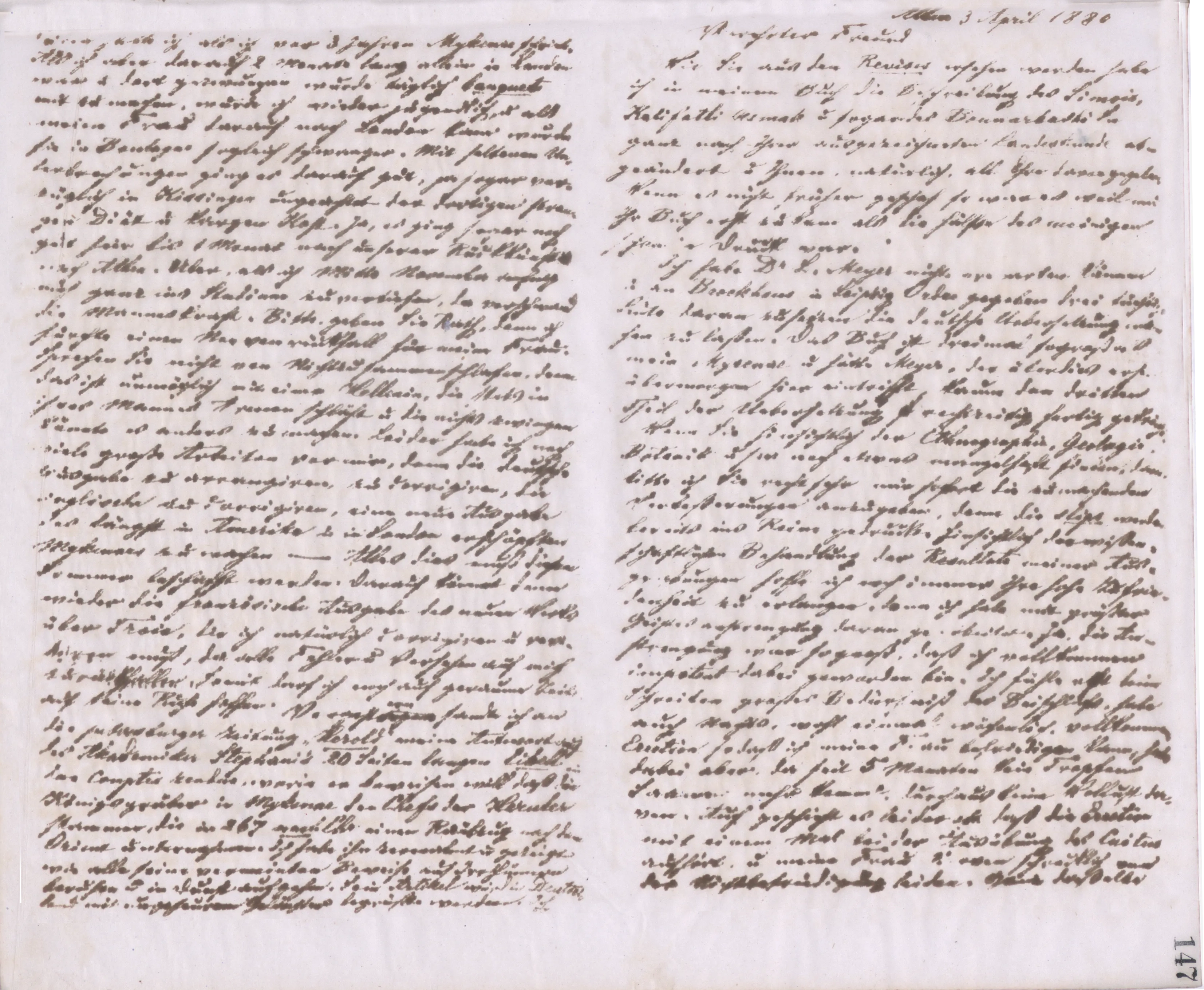

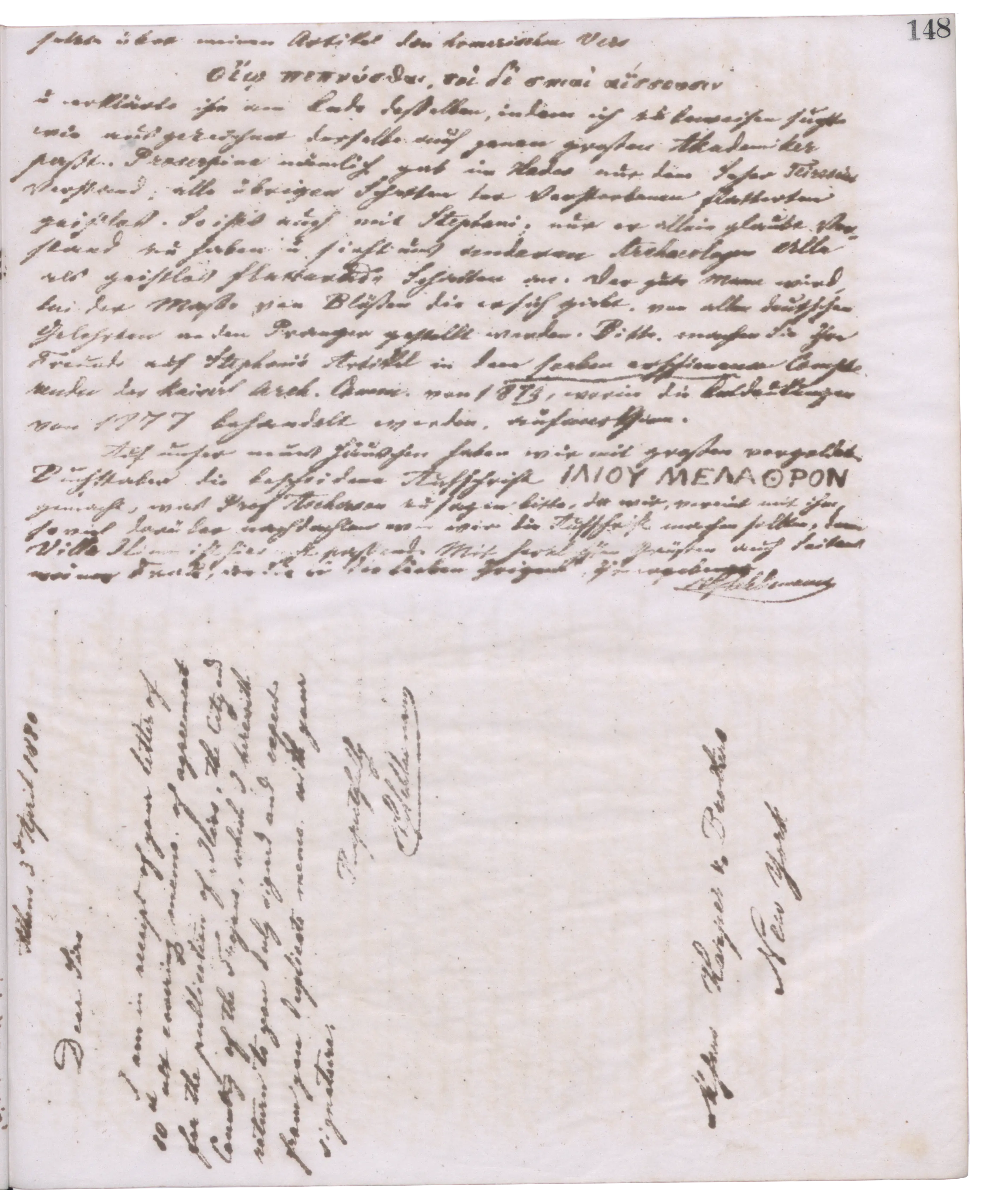

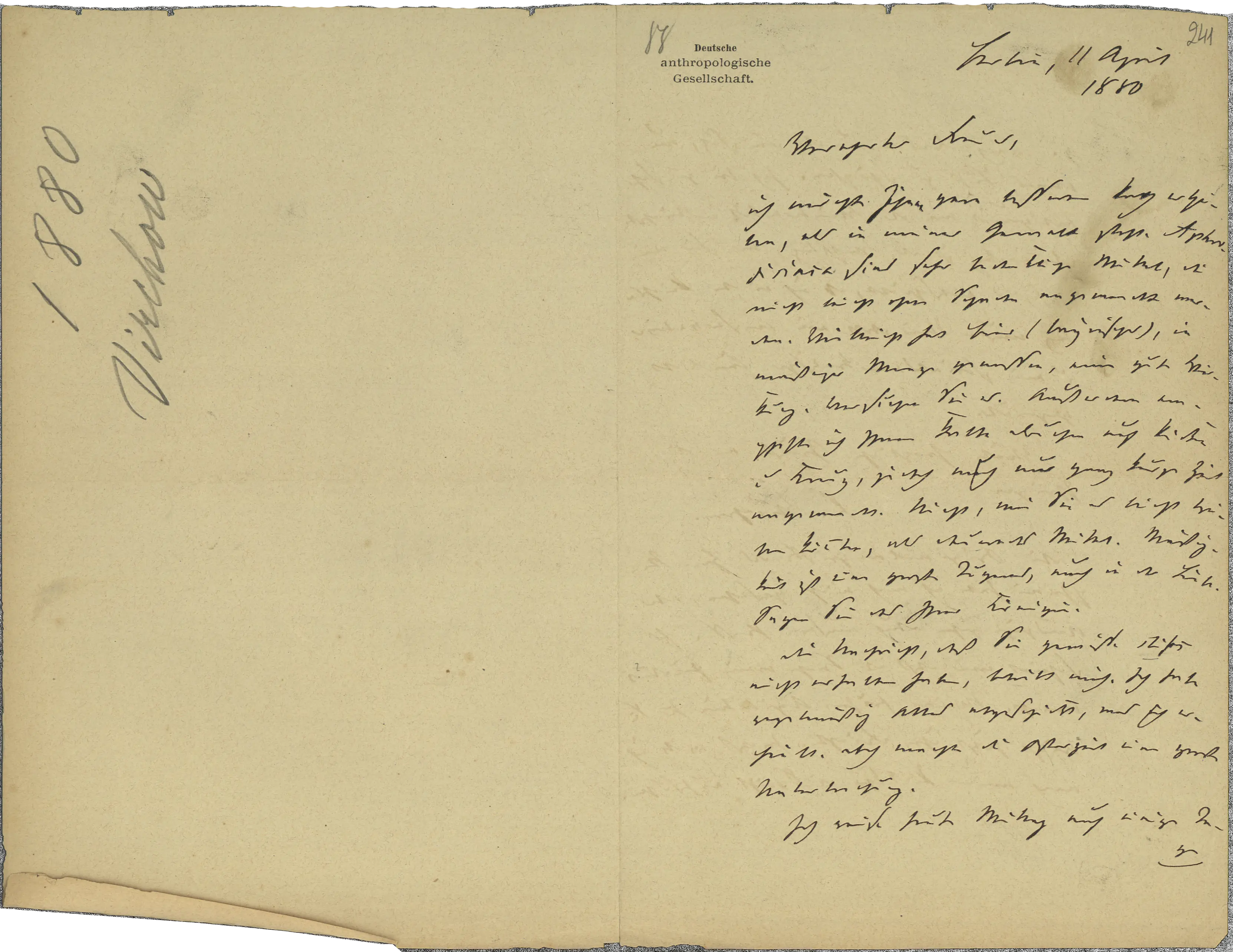

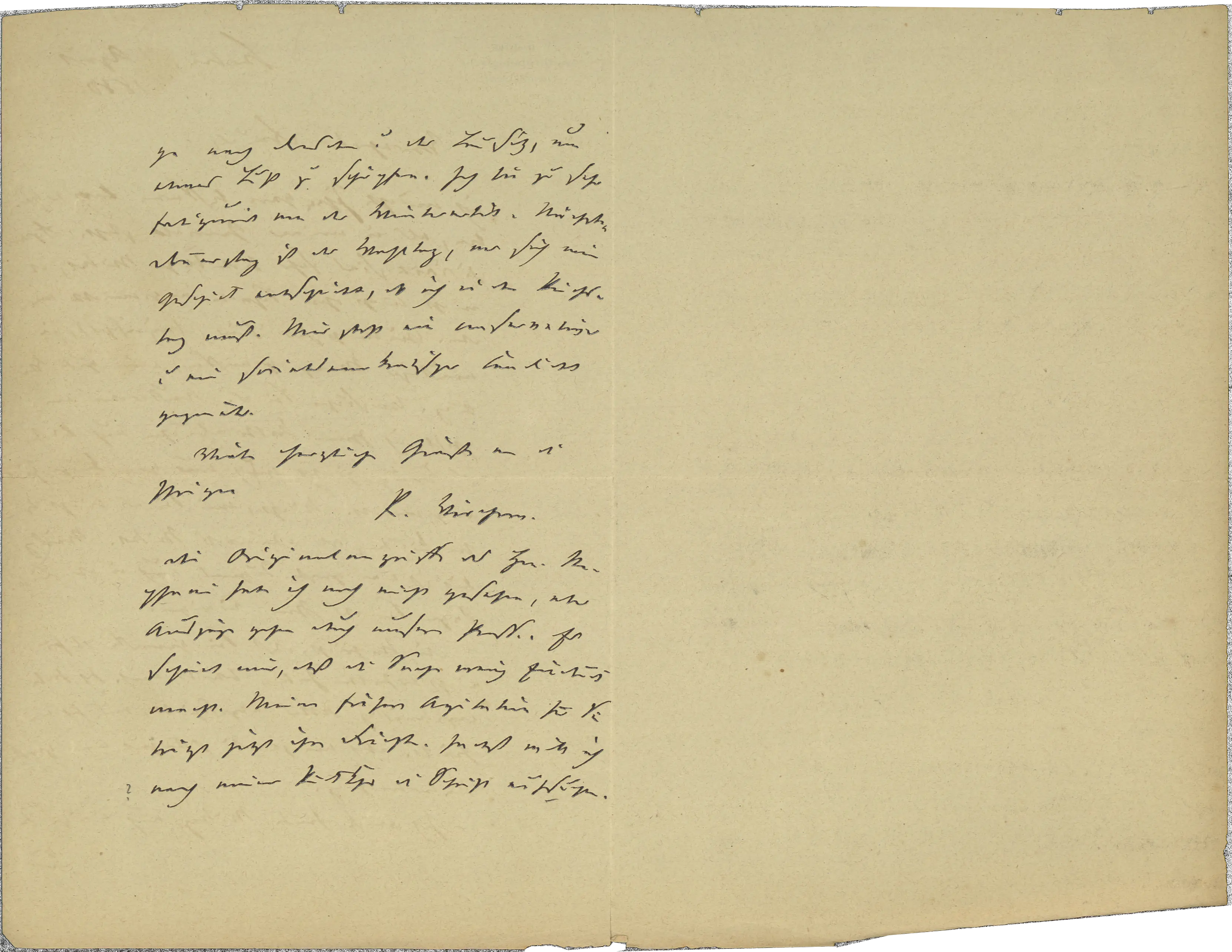

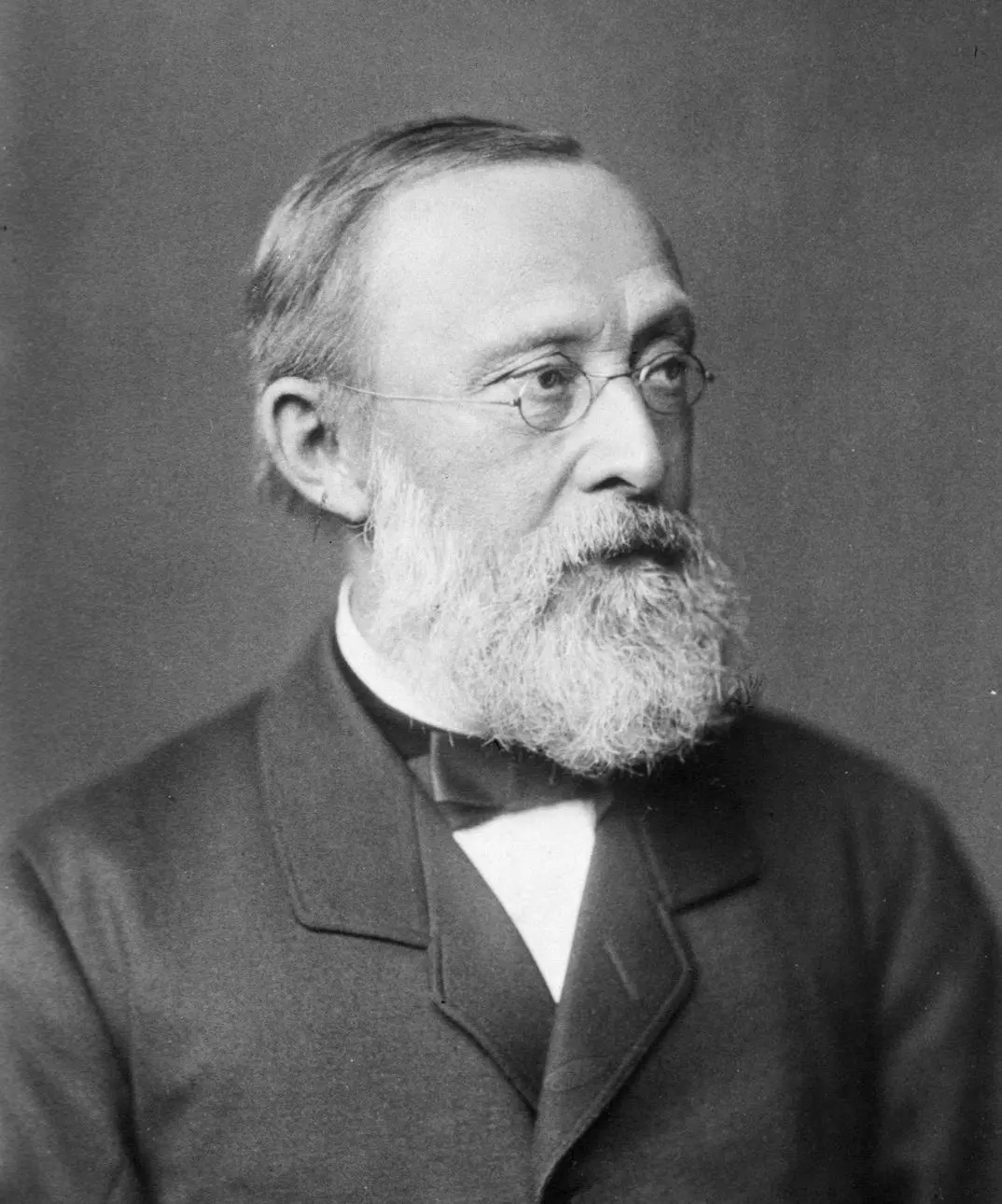

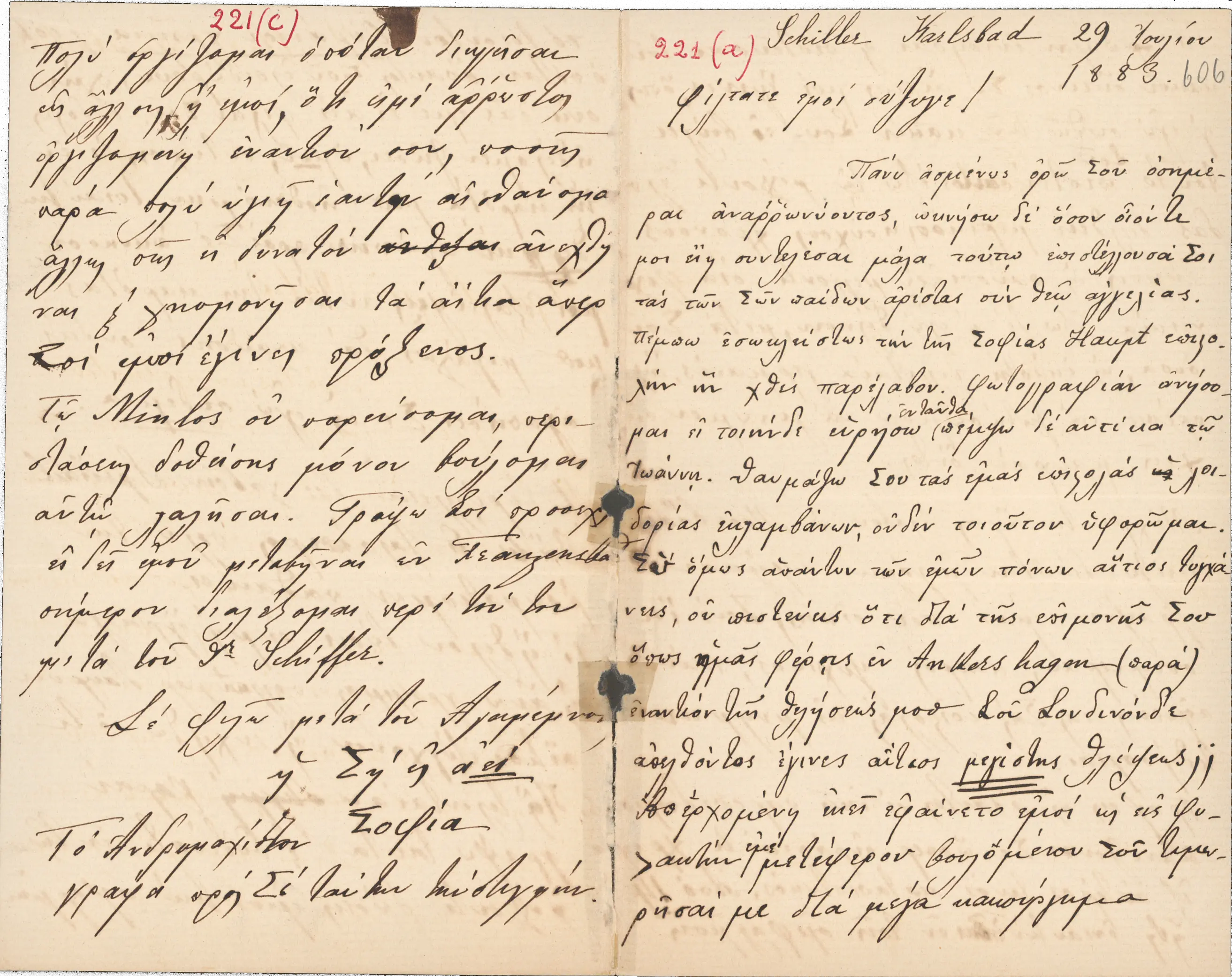

Danae Koulmasi lays special emphasis on the couple's private life, and despite the difference in age and the prudishness surrounding sexuality in the 19th century, it would seem that there was a strong sexual bond between them. Although there are hints of this here and there in the correspondence, most of the information comes from the correspondence between Heinrich and the doctor/anthropologist Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902), a contemporary of Schliemann and a family friend. Both Heinrich and Sophia turned to him for advice when they encountered problems in their relationship (Koulmasi 2006, pp.224-228).

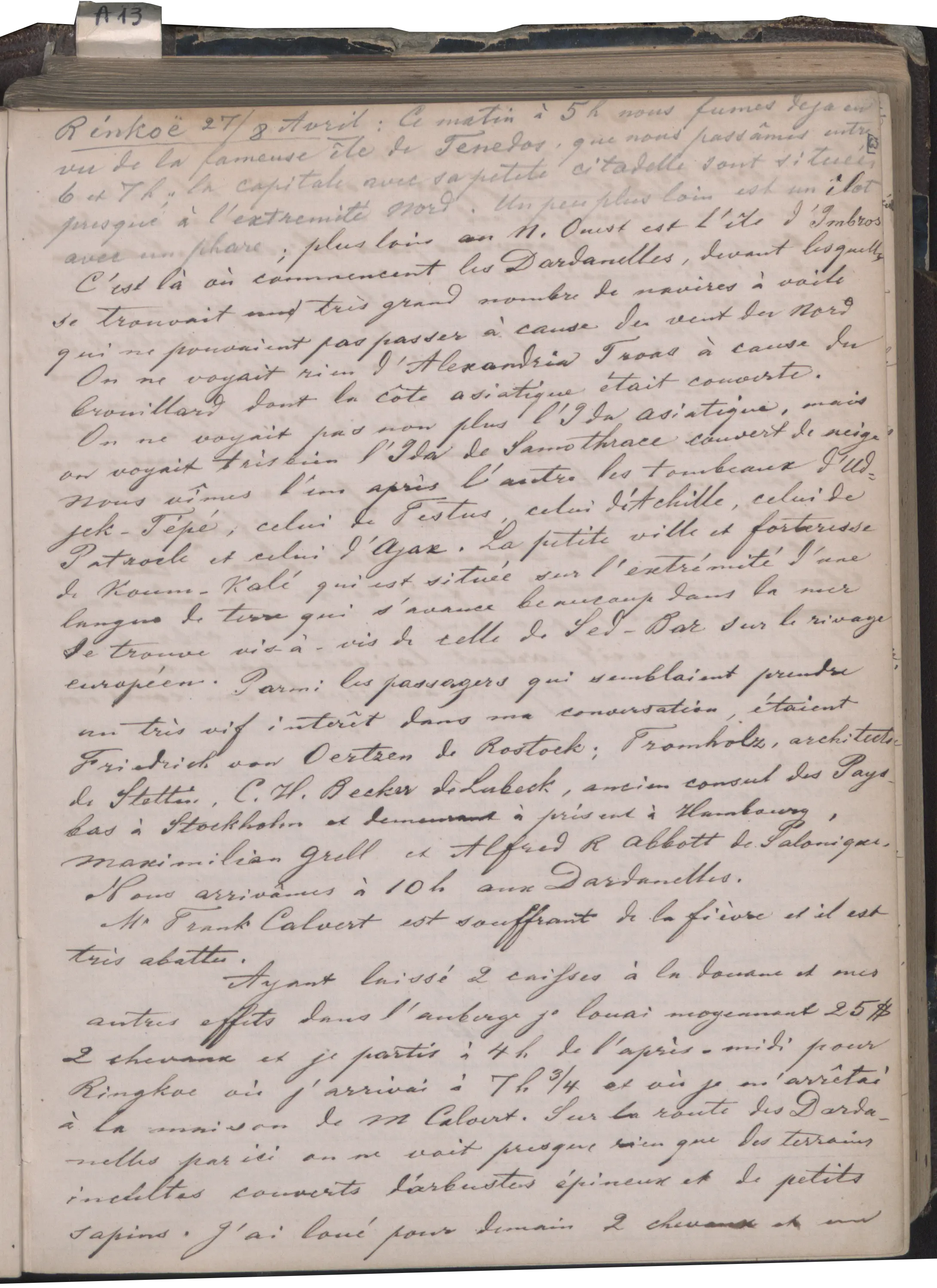

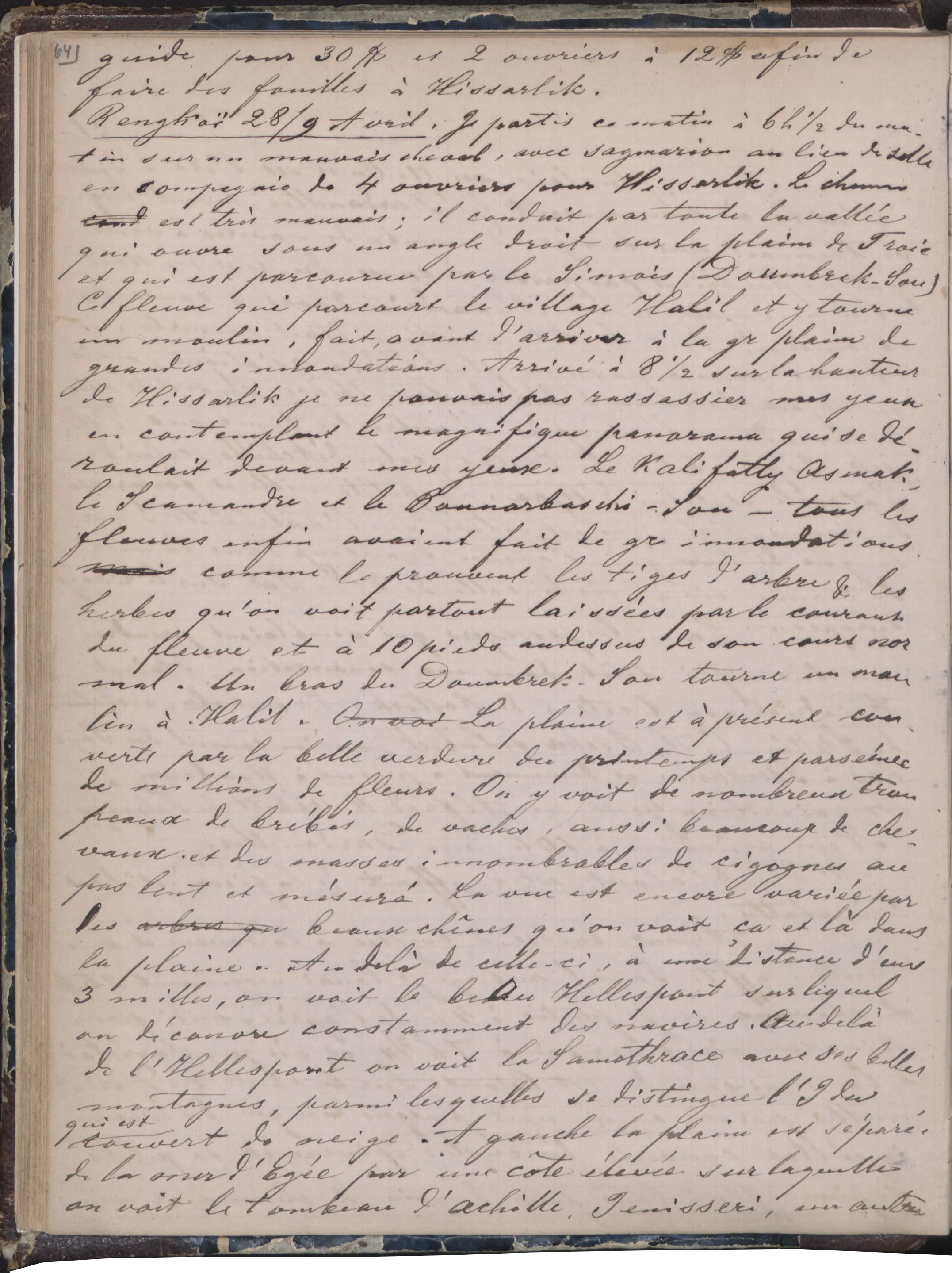

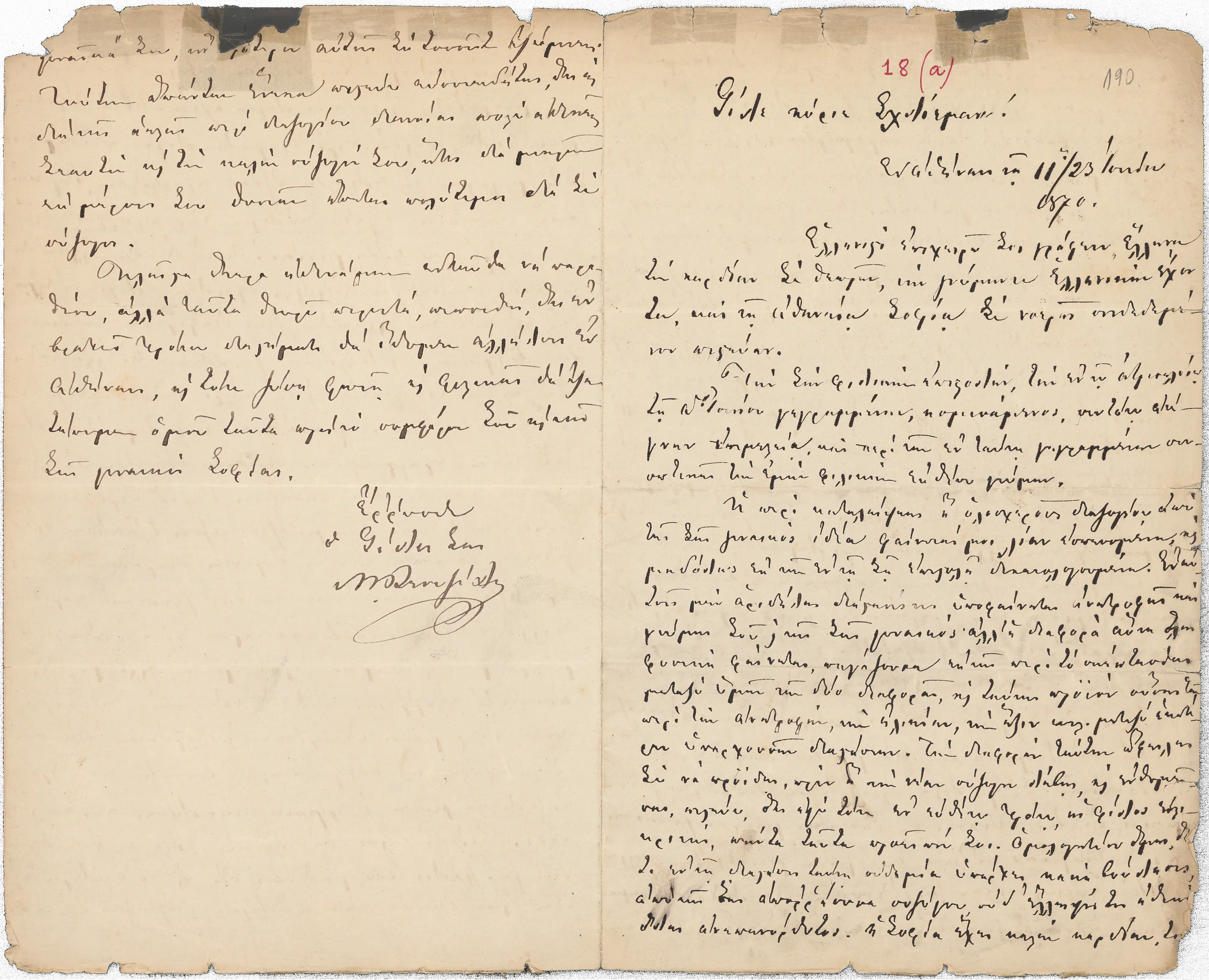

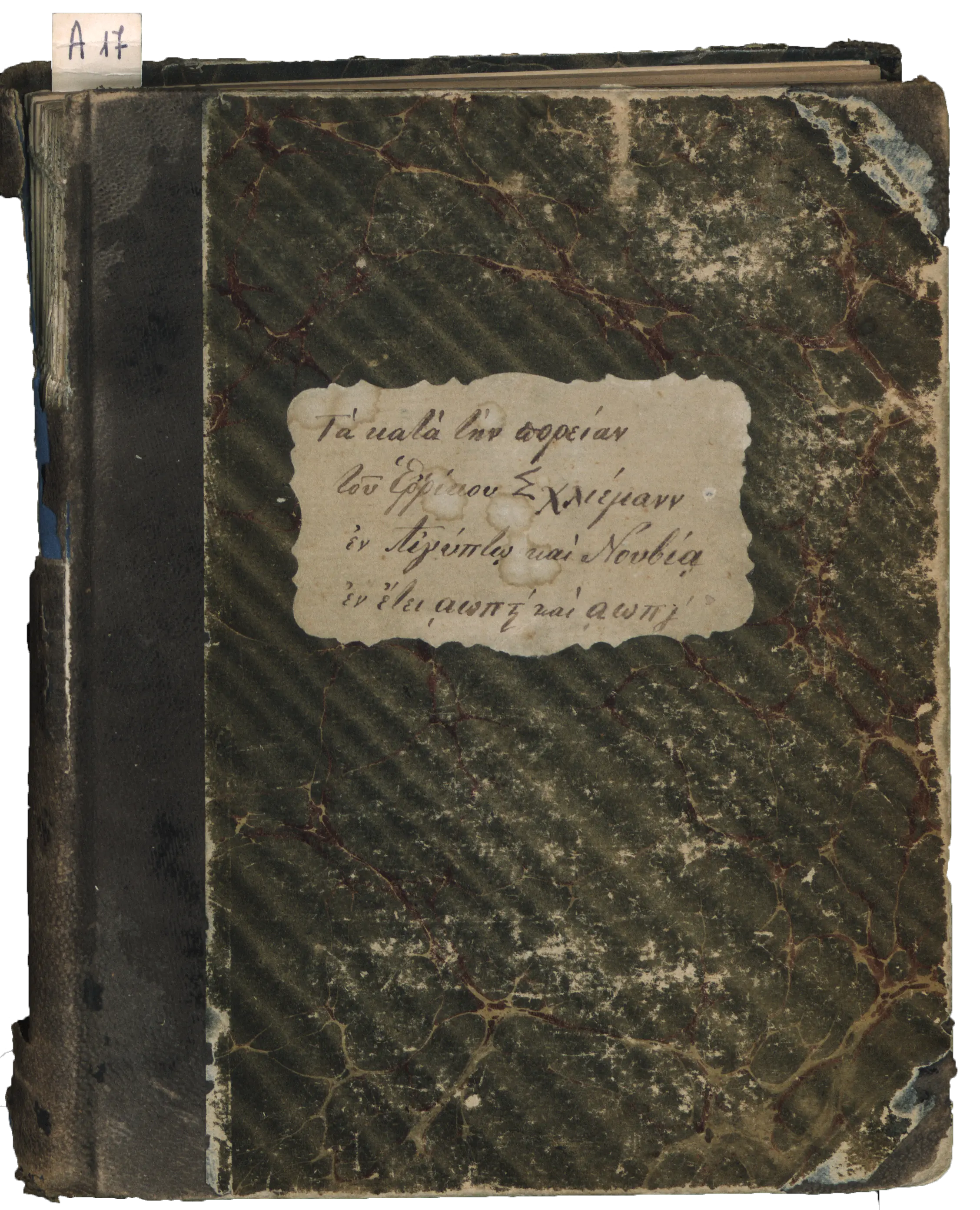

4. 'I AM TRYING TO MAKE SOPHIA AN ARCHAEOLOGIST'

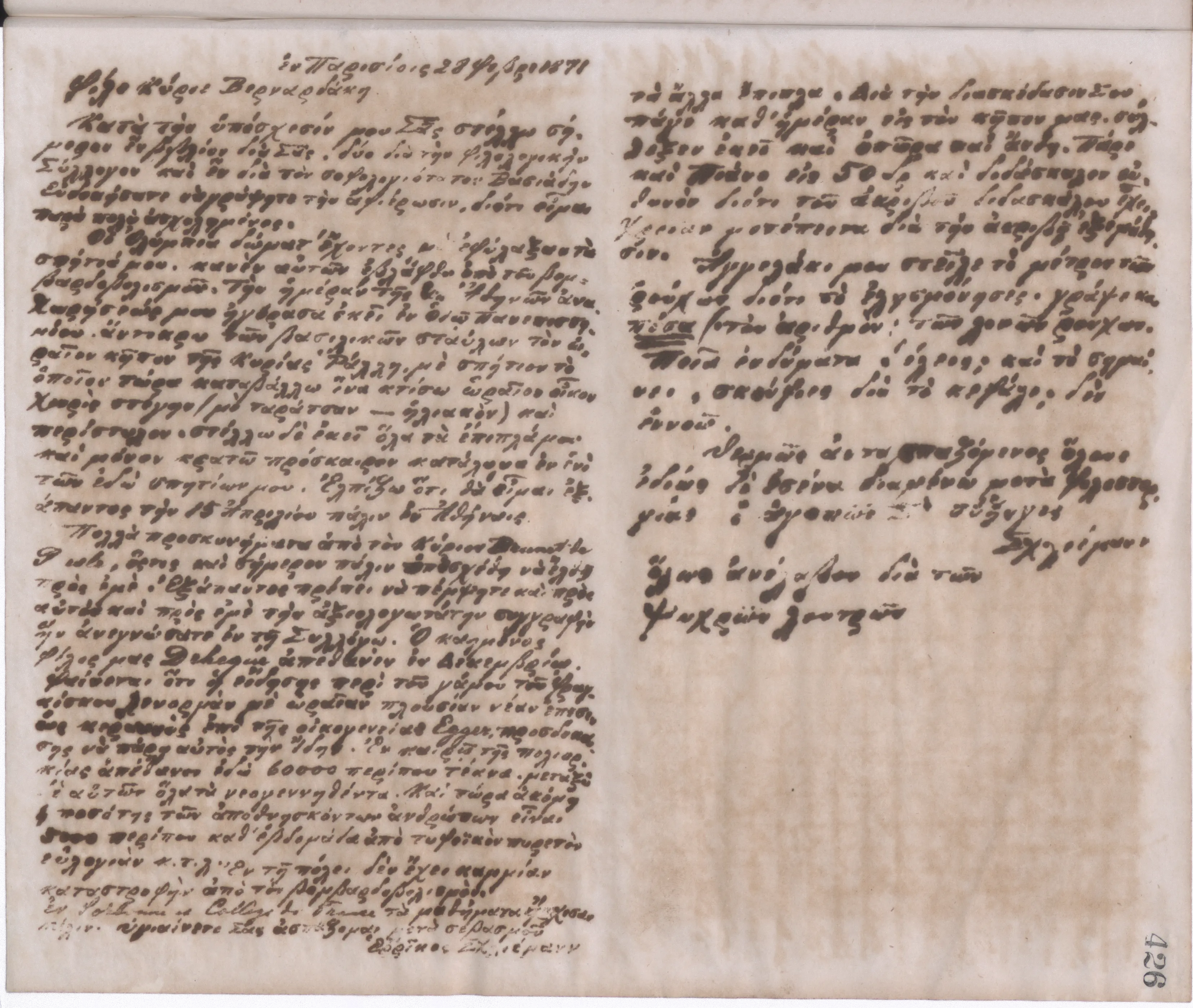

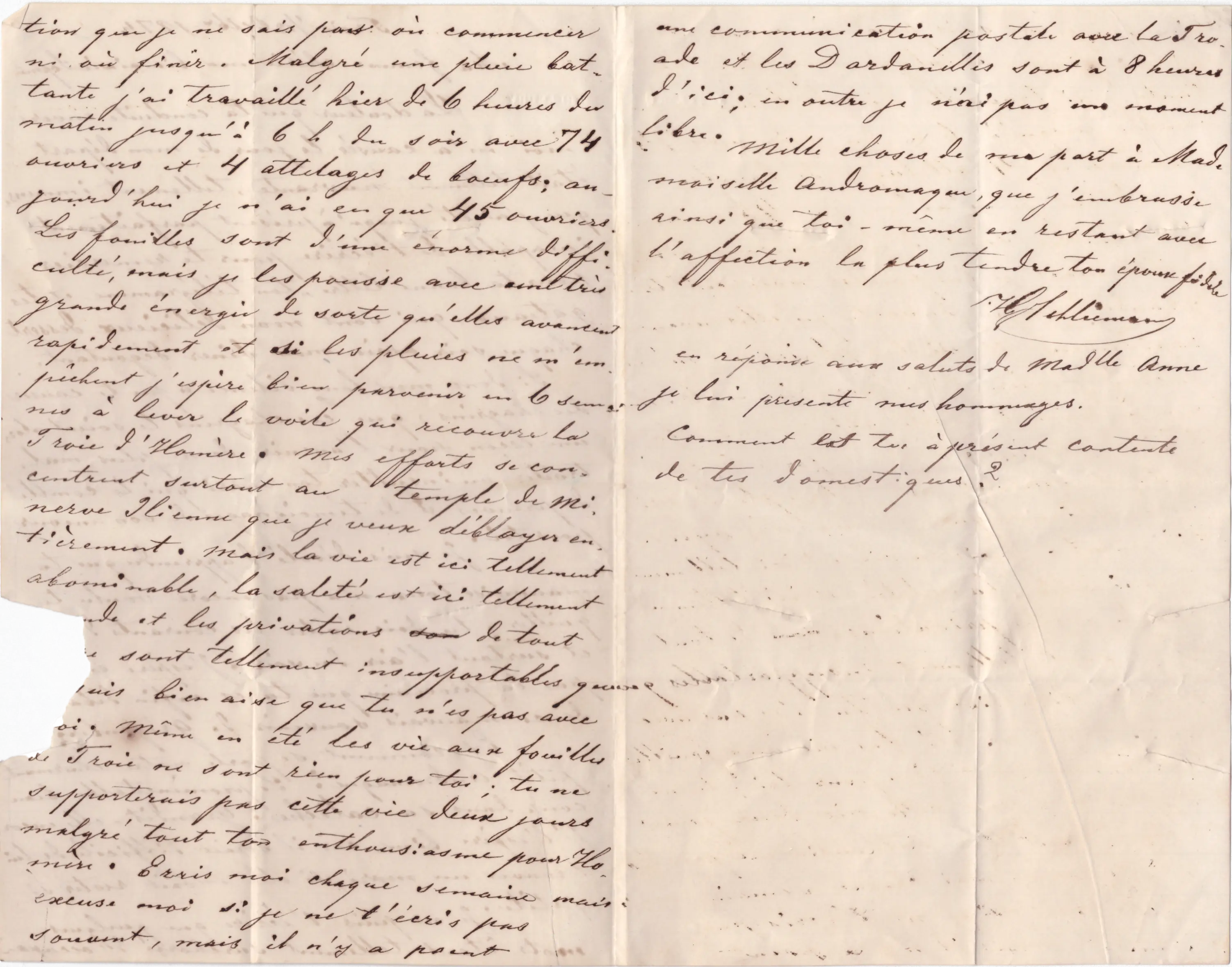

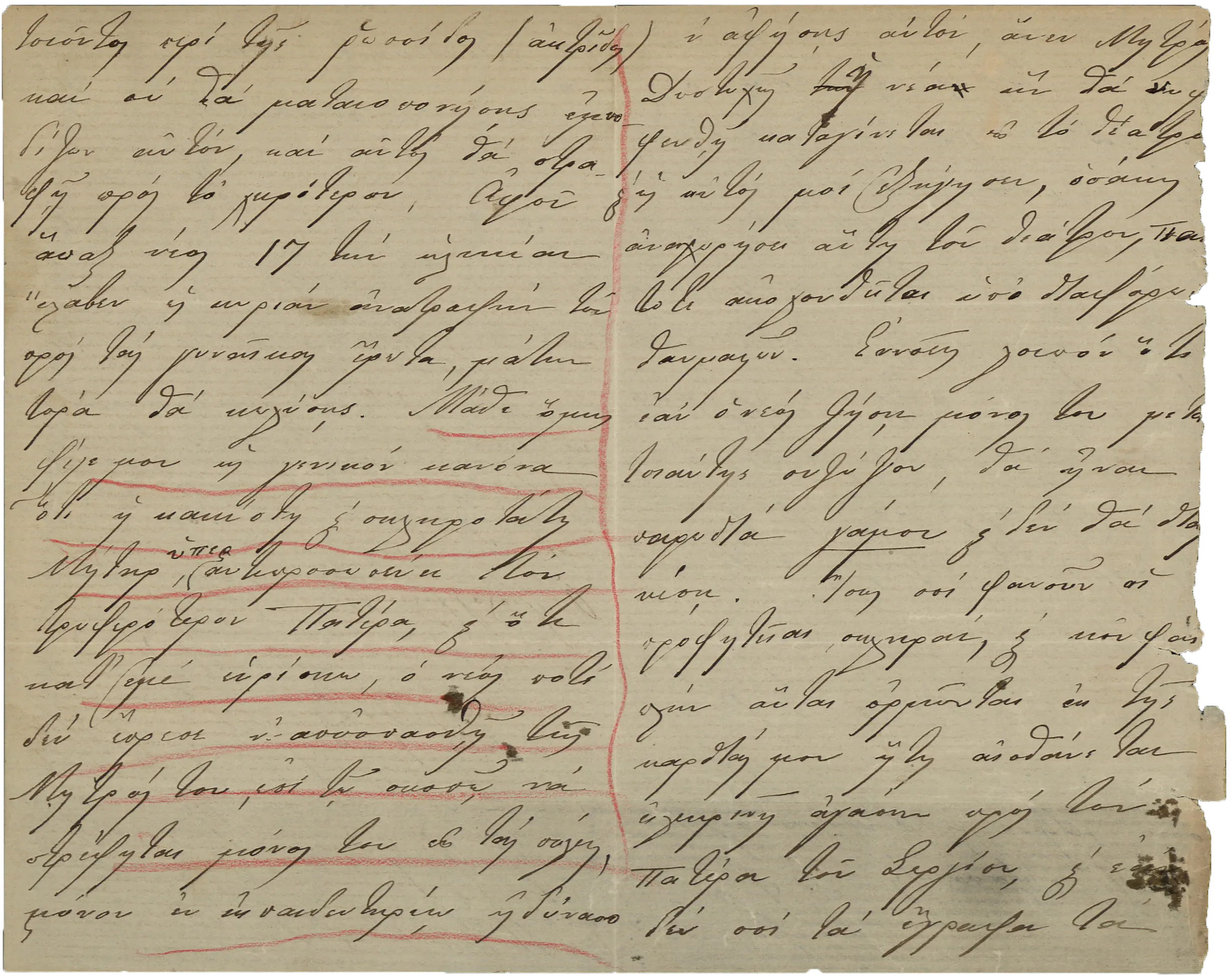

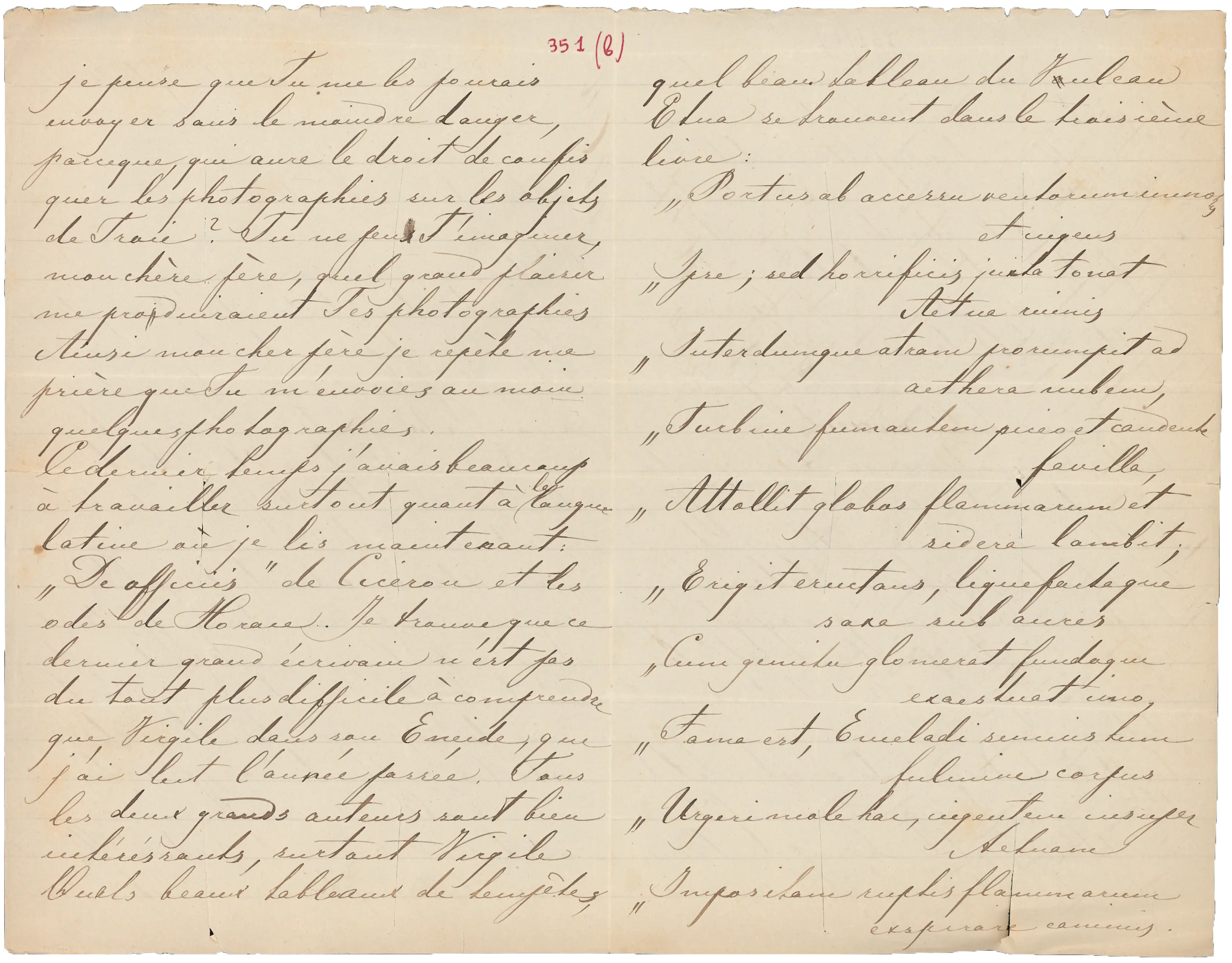

If there was one thing that Schliemann wanted more than Sophia, it was her active participation in his excavations. This was quite unusual at a time when the roles of the spouses were distinct and married women were not involved in their husbands' professional life. Sophia refused to accompany Schliemann in the autumn of 1871 on his first official excavation at Troy, with the excuse that Andromache was too little to be left in the care of others. Schliemann did not write to her for a while, and when he decided to reply (in French) he reminds her of how hurt he was by her refusal to go with him to Troy.

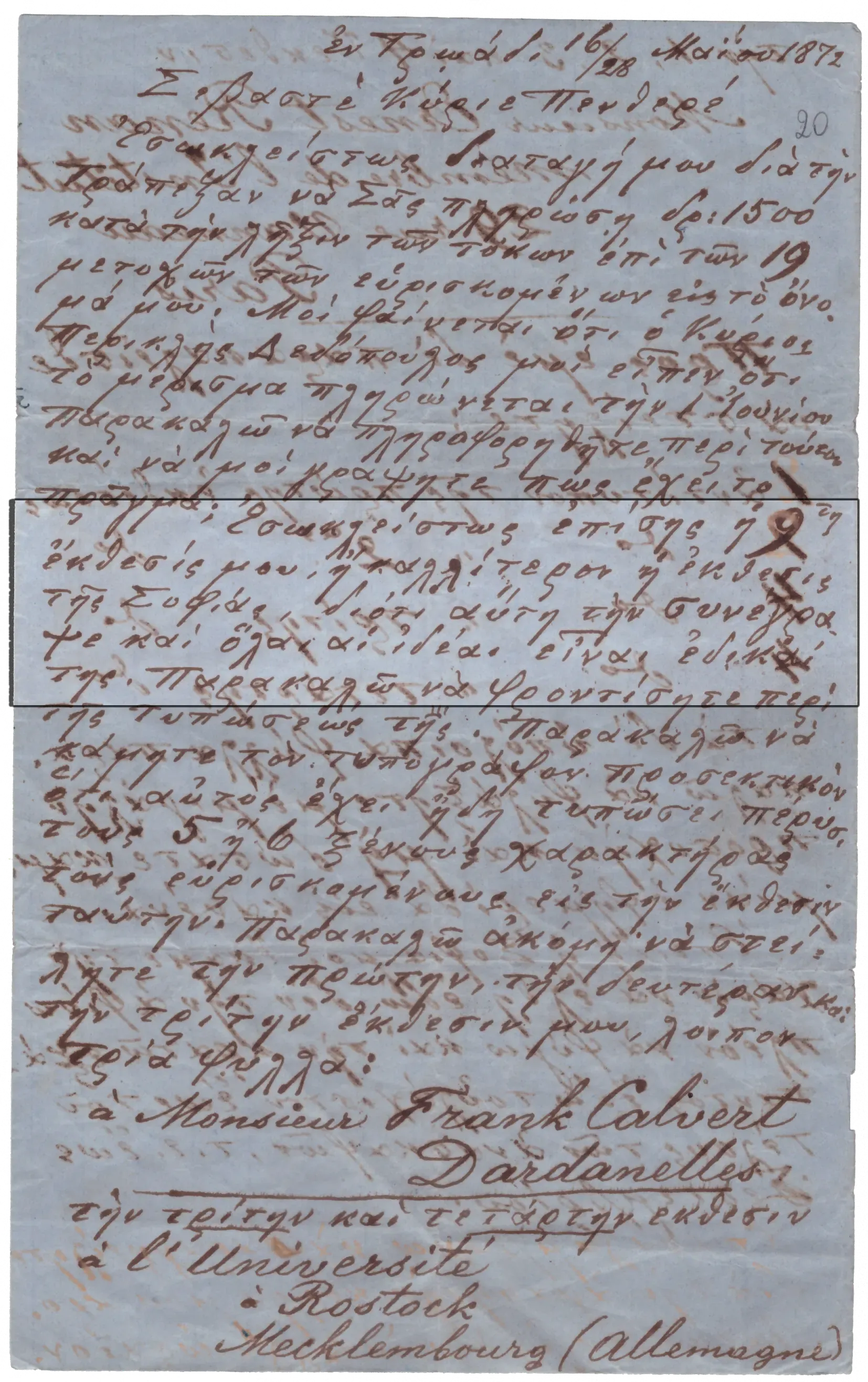

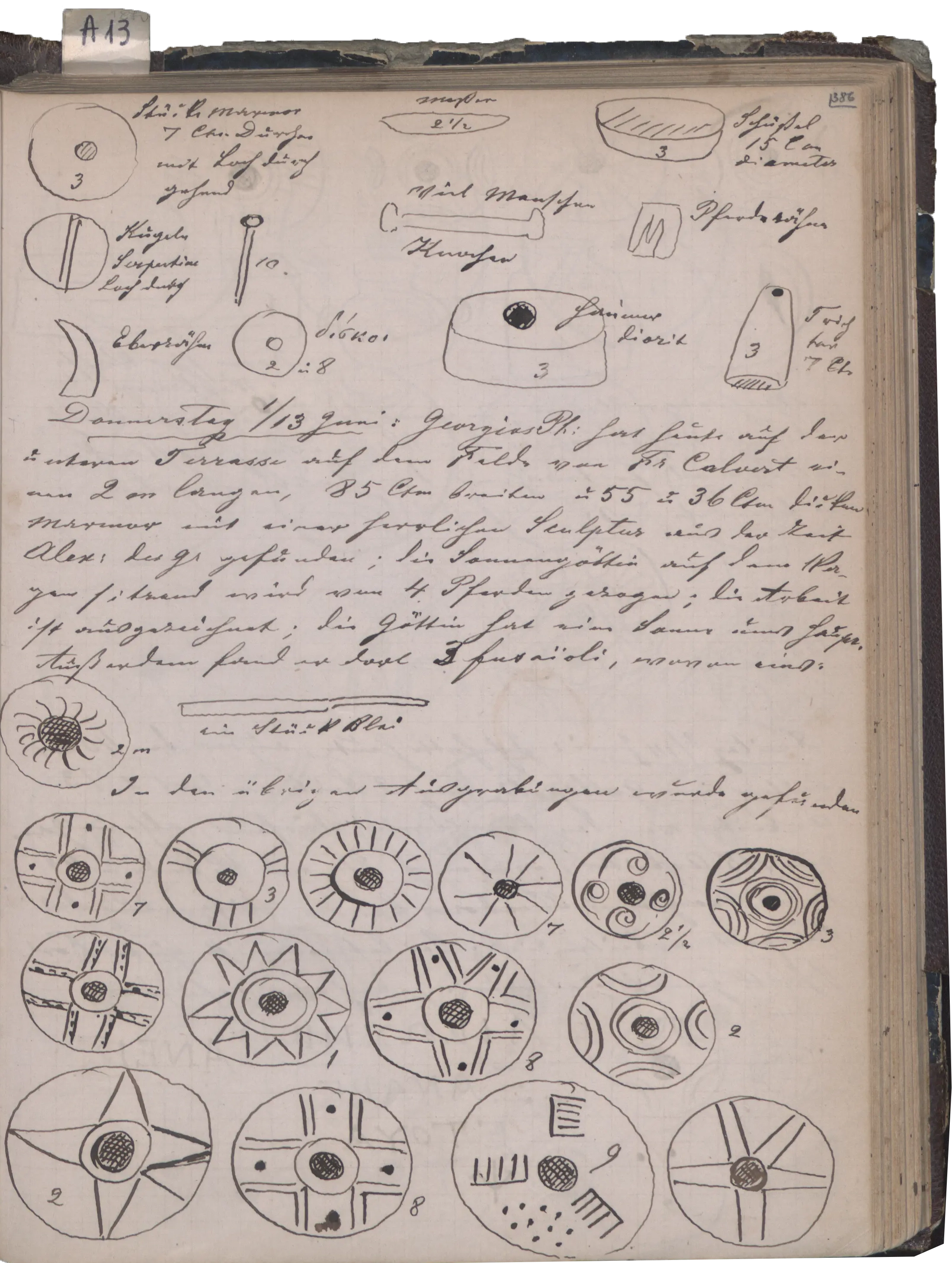

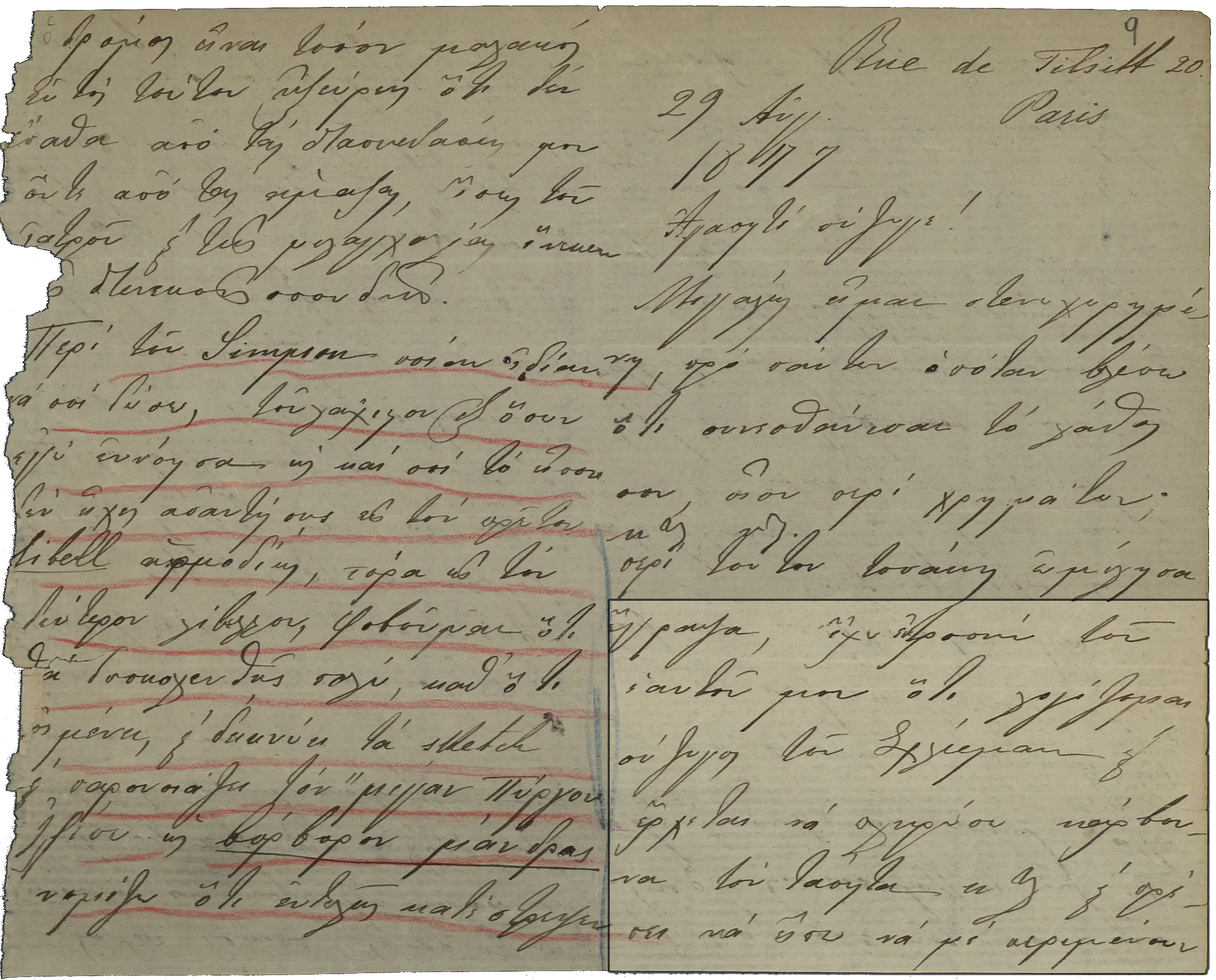

After the 1871 excavations, Schliemann returned to Troy in April 1872. By late May, Sophia went to join him, leaving one-year-old Andromache with her parents. At first, Schliemann set her to oversee two workers, but later he placed her in charge of an excavation trench. It is clear he wanted Sophia with him at the dig and not in some subsidiary role in the excavation house. During this time, he sent his father-in-law a report of the excavations for printing: 'I also enclose my 9th report, or rather Sophia's report, since she co-wrote it and all the ideas are hers.' He not only relied on her to write his reports about the excavation but had no hesitation in giving her credit for them.

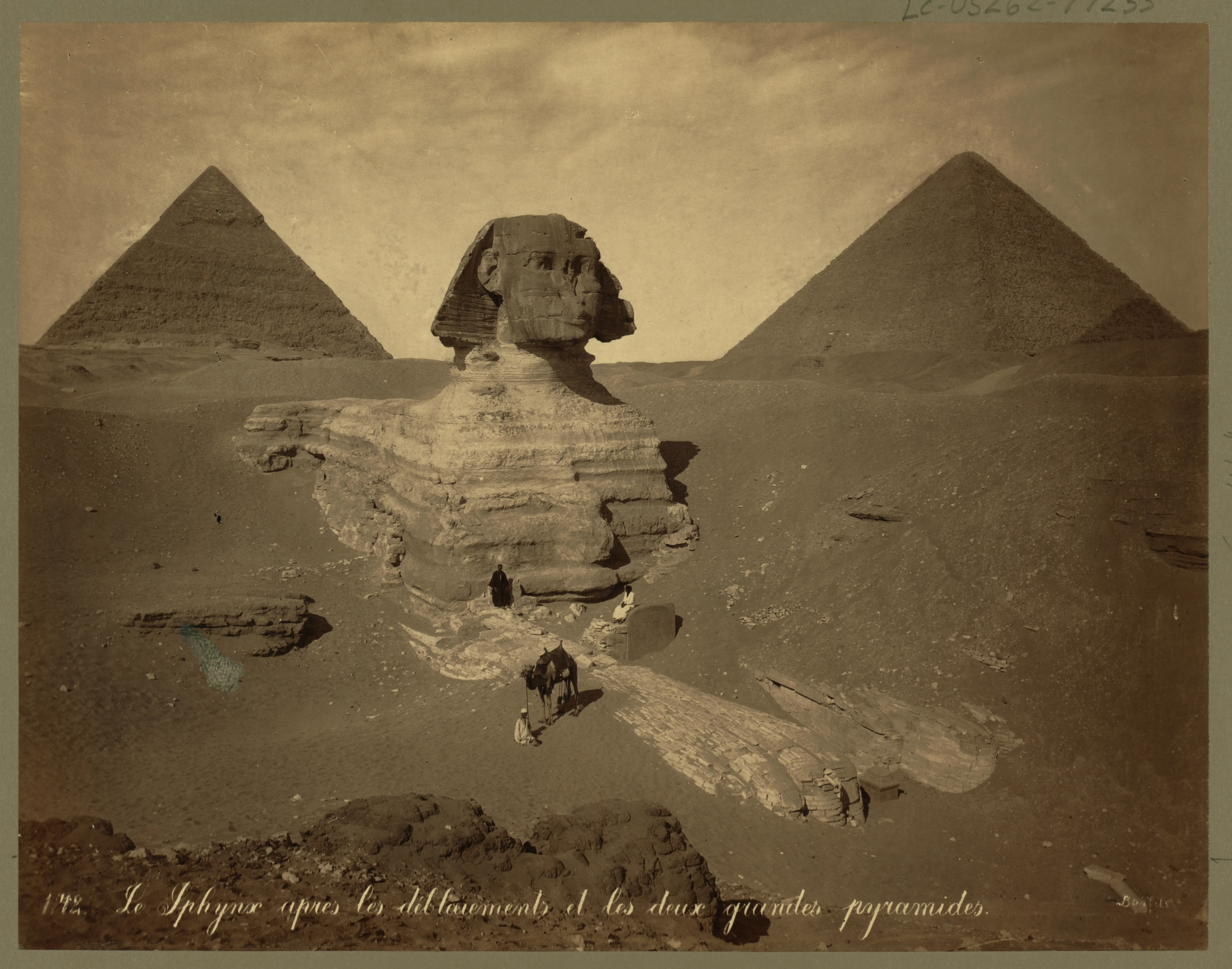

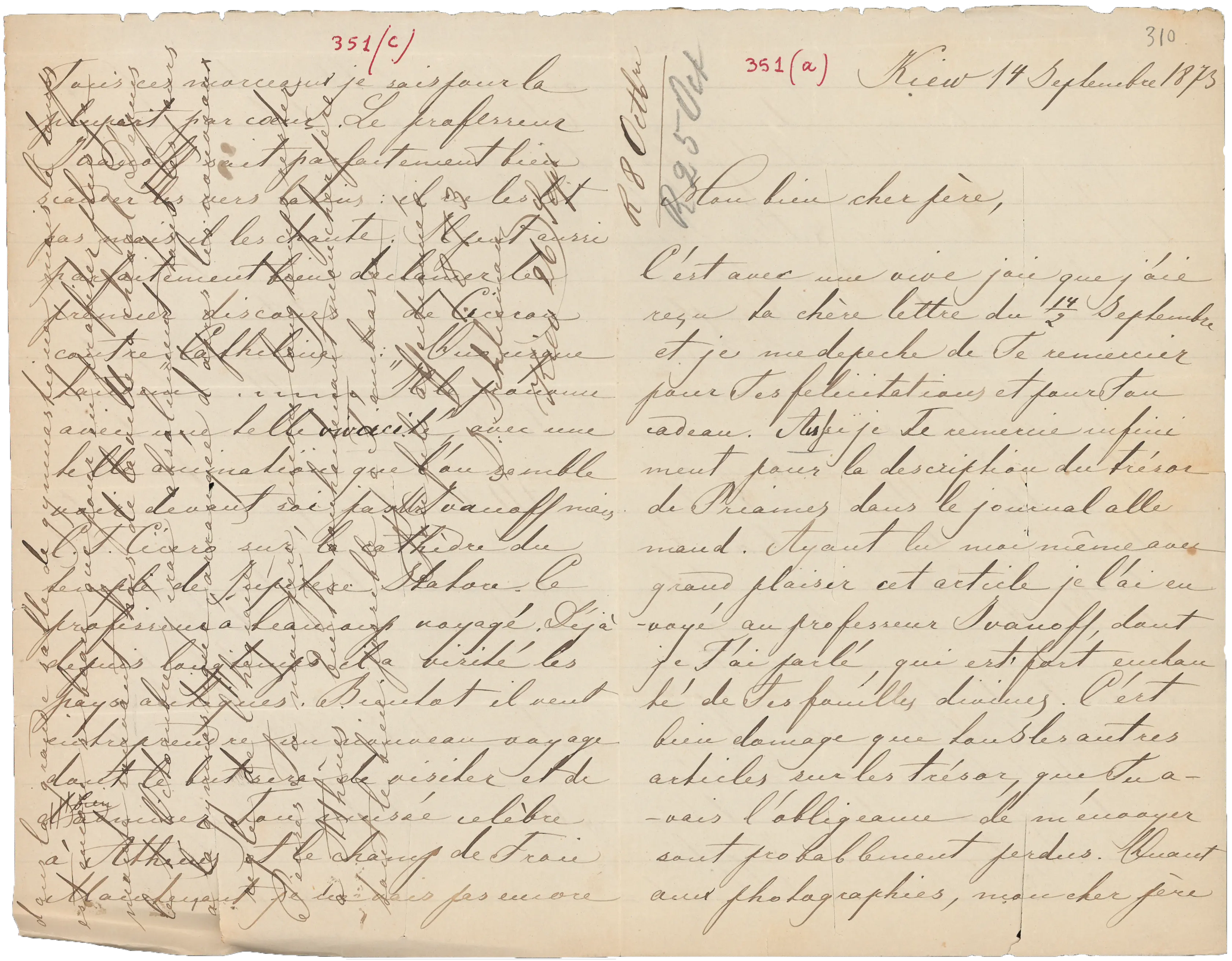

The excavations at Troy were continued in February 1873, when the cold was severe and the weather bad. Sophia travelled to Troy in April, intending to stay with him throughout the excavation. This time he put her in charge of the excavations at Pasha Tepe (Koulmasi 2005, p.129), but the news of her father's death obliged her to leave Troy at the beginning of May. At the end of May, Schliemann discovered the Treasure of Priam. He did not share what was possibly the most important moment of his life with Sophia, even though in his books he asserted that she was with him at the discovery. Much ink has been spilled by researchers in their attempt to explain why Schliemann invented Sophia’s presence at the discovery of the Treasure. The most likely answer is in a letter he sent to the Director of the British Museum, Charles Newton, on the 27th December 1873 (the letter is in the Museum Archives and was published by Lesley Fitton).

“... On acc[oun]t of her father’s sudden death Mrs Schliemann left me in the beginning of May. The treasure was found end of May; but since I am endeavouring to make an archaeologist of her, I wrote in my book that she had been present and assisted me in taking out the treasure. I merely did so to stimulate and encourage her, for she has great capacities. So f[or] i[nstance] she has learned Italian here in less than two months.”

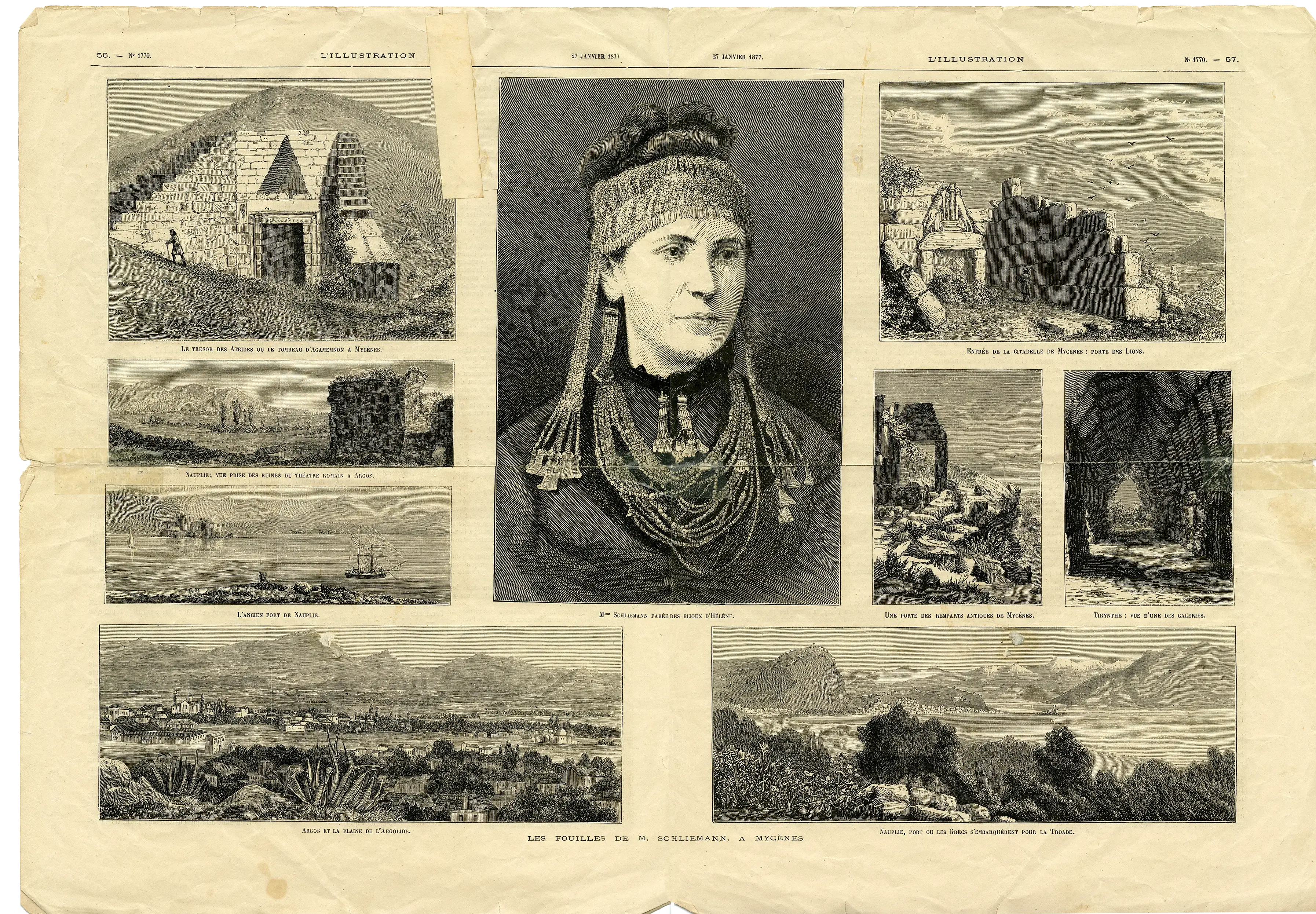

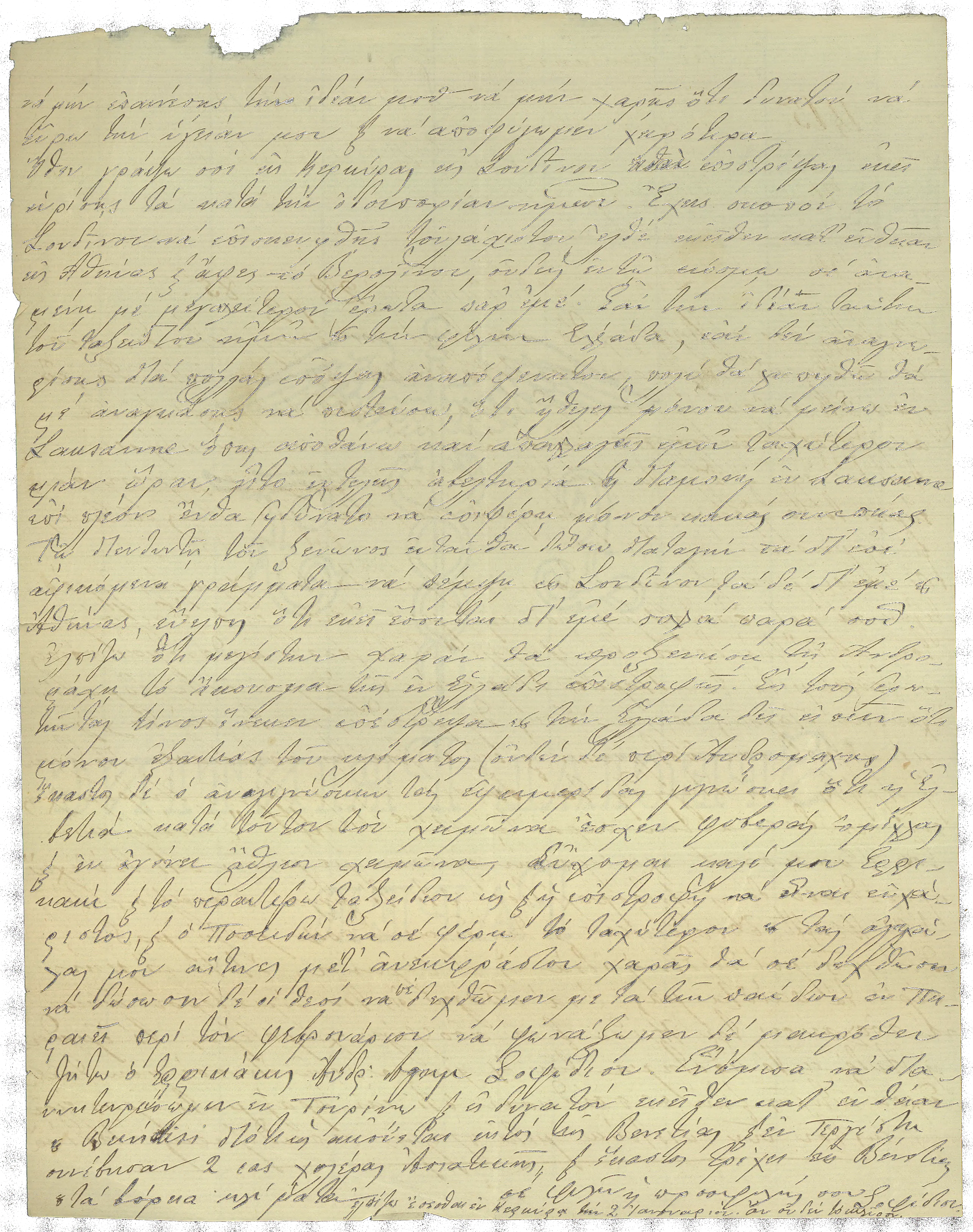

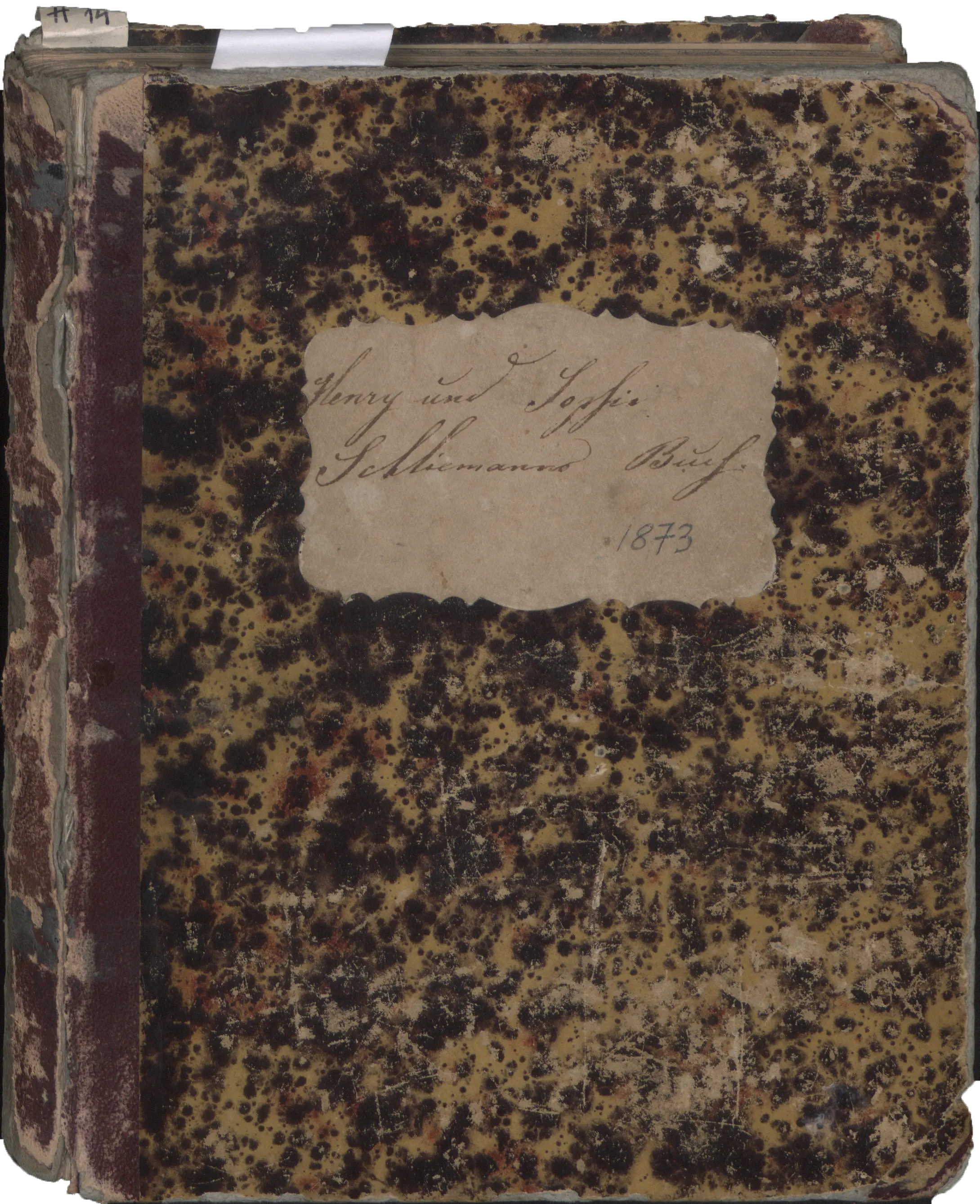

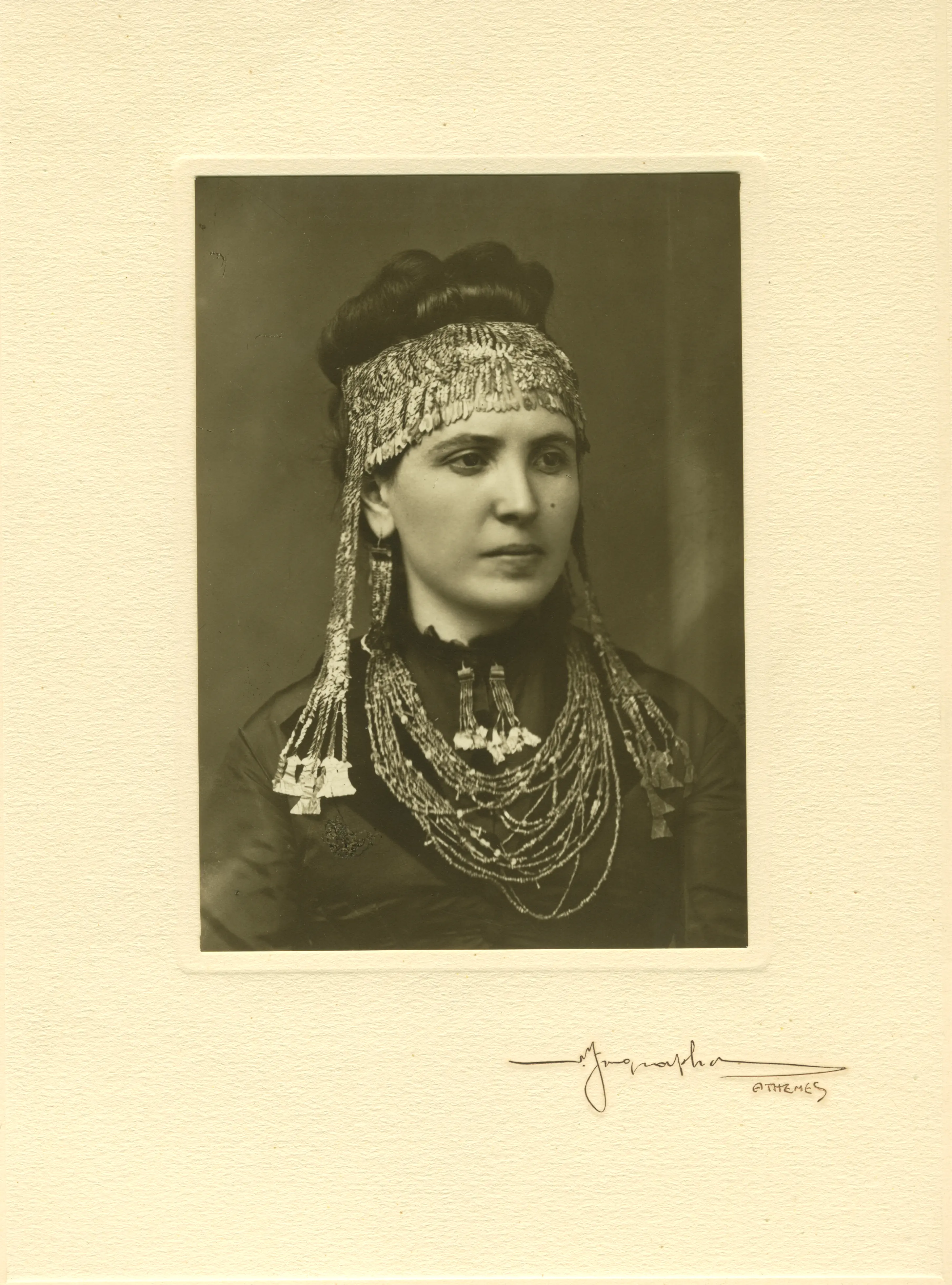

On the hard cover of the diary of the excavations at Troy for the year 1873, Schliemann wrote 'Henry und Sophia', even though she was only with him at the dig for a few days that year. Sophia never refuted Schliemann, even after his death. In fact, sometime between 1873 and 1877 Sophia posed for a photograph as Helen of Troy, wearing part of the so-called Treasure of Priam. She would be identified by this image not just during her lifetime but after it. It remains the most widely reproduced photograph on the covers of books dealing with Heinrich Schliemann and the excavations at Troy.

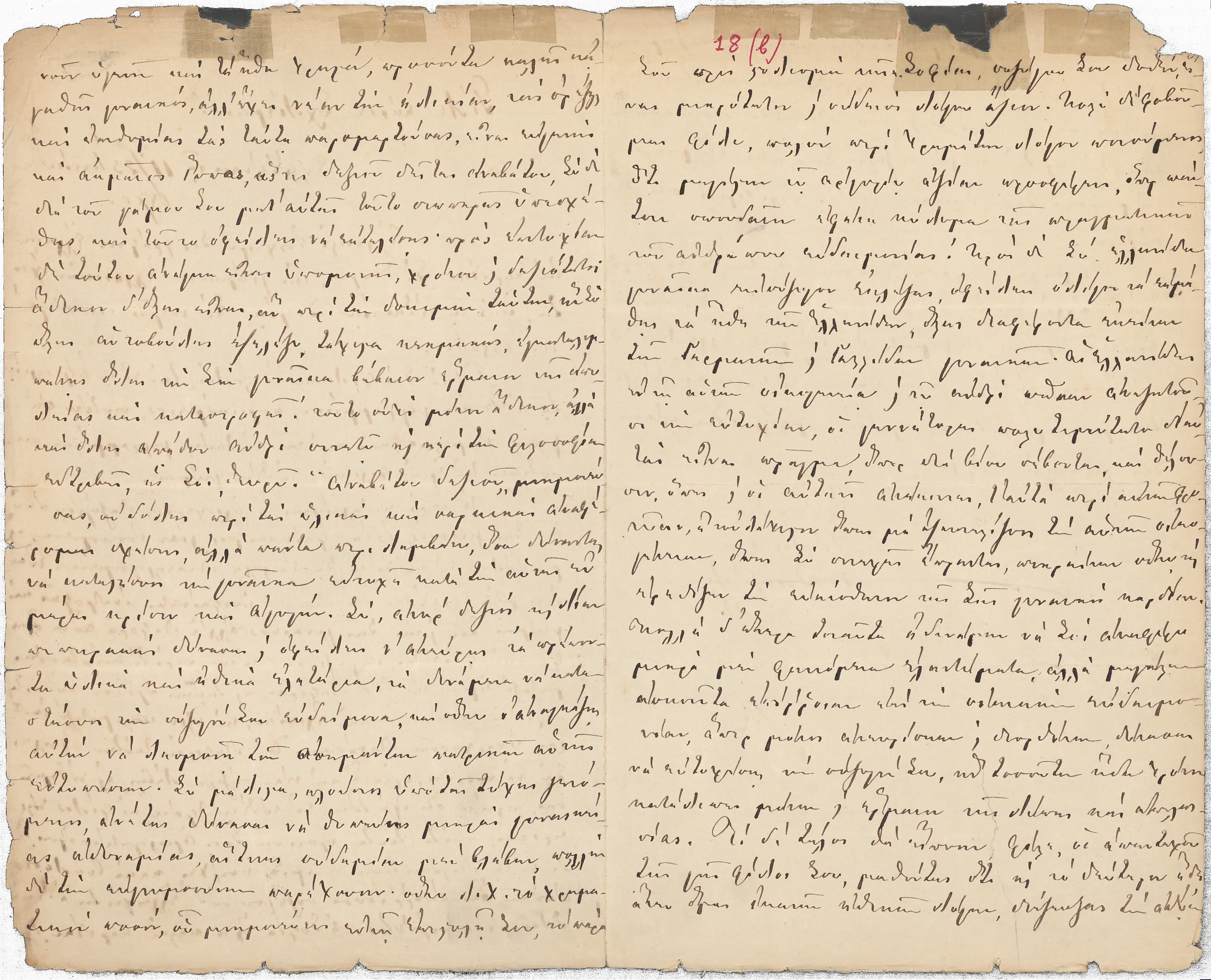

Insofar as she was able, particularly before the birth of their second child in 1878, Sophia accompanied Heinrich to the excavations and actively participated in the laborious everyday life of the site. It should be noted (and has gone relatively unremarked in the research) that Sophia suffered many miscarriages during her life. At Mycenae she was with him at the discovery of the intact shaft graves of Grave Circle A in 1876. Once again, Schliemann drew attention to her presence, showing her participation in the excavation. (On the other hand, he chose to downplay the role of the archaeologist Panagiotis Stamatakis who had been sent by the Archaeological Society to oversee the excavations at Mycenae). We learn from Stamatakis's diaries (published by Vasilikou in 2011) that in some cases Sophia conducted herself with a regal haughtiness which astounded Stamatakis, who wrote in a letter to Stephanos Koumanoudis, secretary to the Archaeological Society: 'My relations with Mr Sch. remain broken off, and we communicate through the foremen. His lady has returned here from Athens, but it would be better if she had not come. For she has been the cause of everything and I much fear the same will happen again' (Vasilikou 2011, p.203).

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

5. MARRIED TO A SOCIOPATH?

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Lynn and Gray Poole Papers.

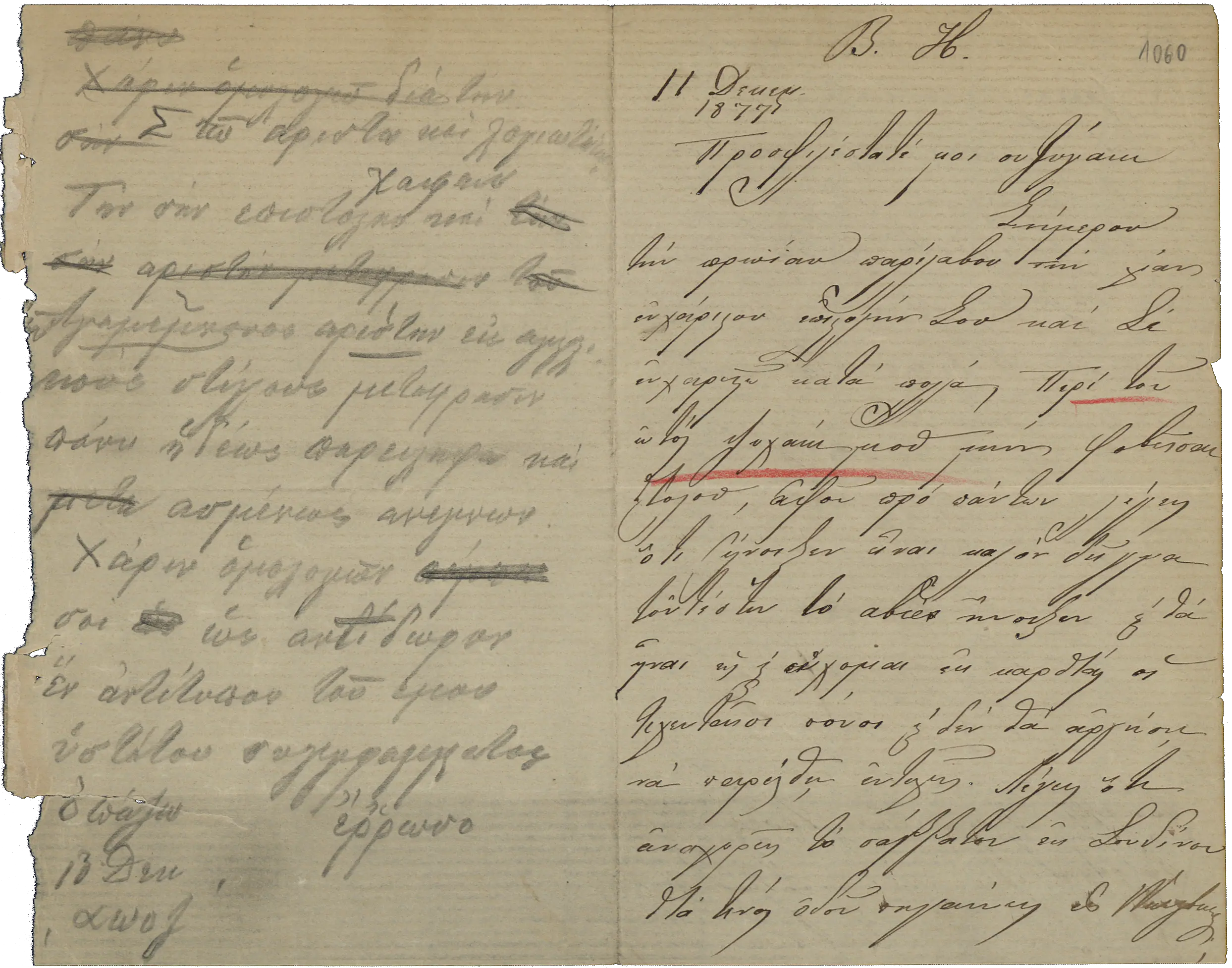

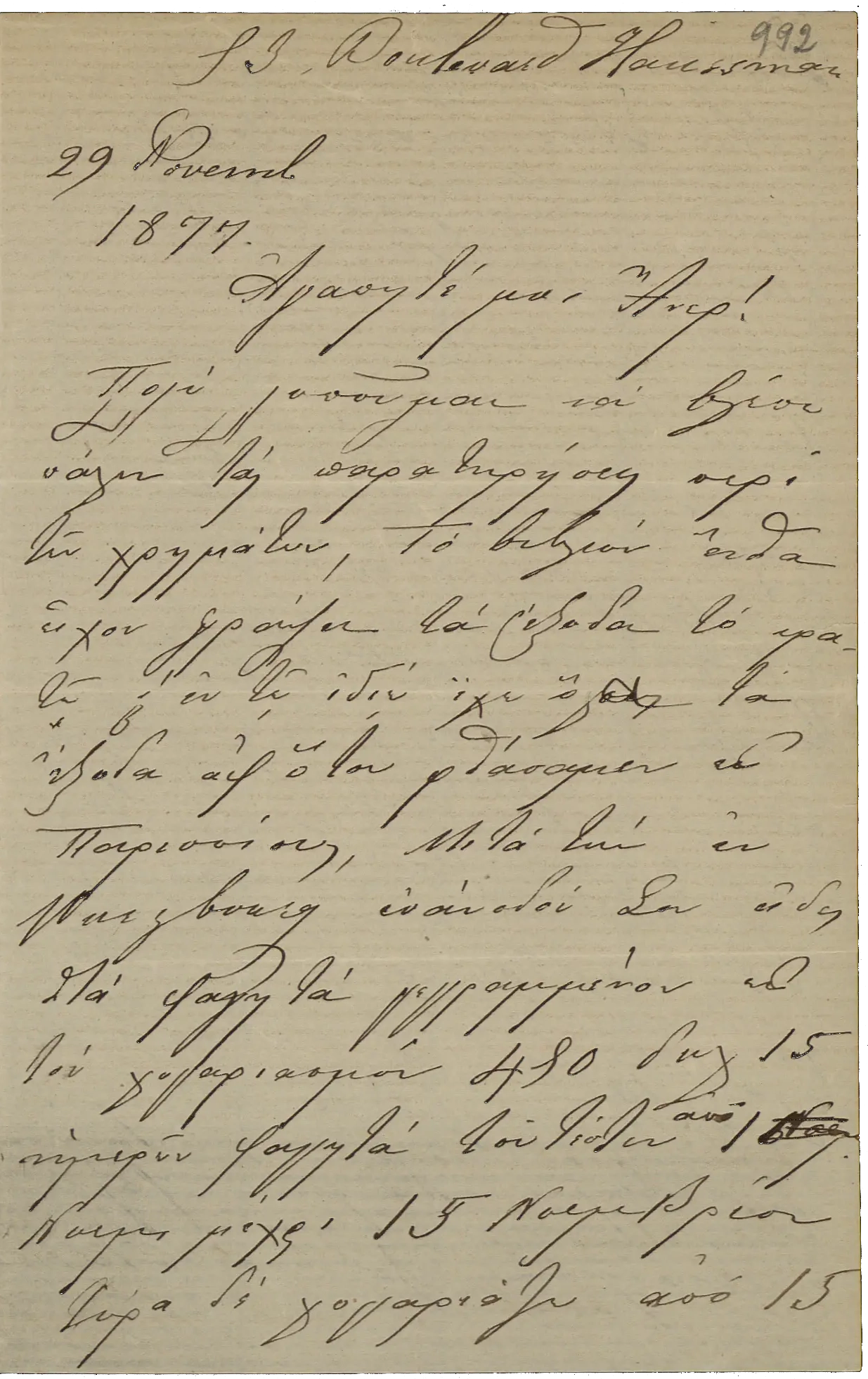

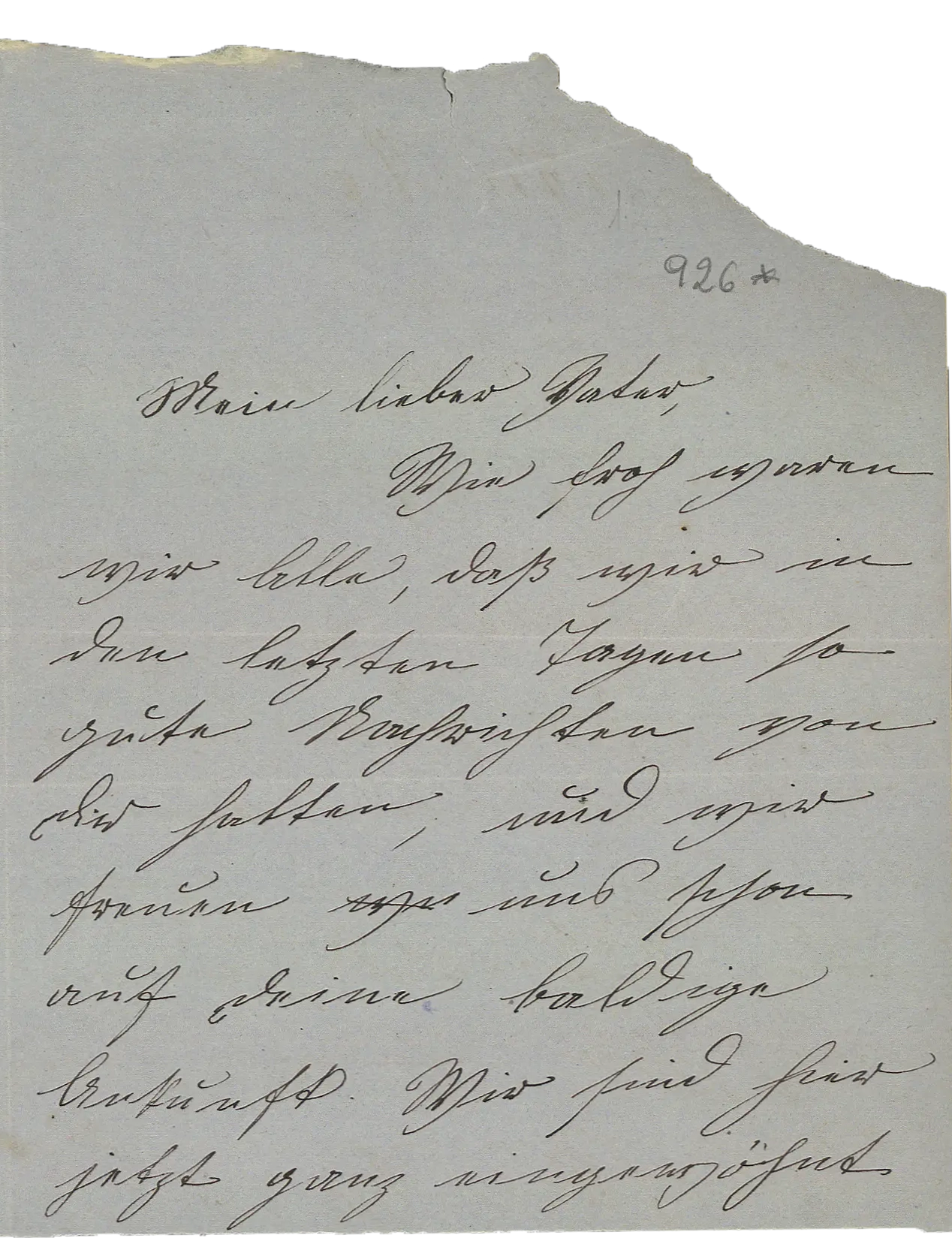

After their successful appearance in London, the couple left for their beloved Boulogne-sur-Mer, where they stayed for five weeks at the Hôtel du Pavillon Impérial.

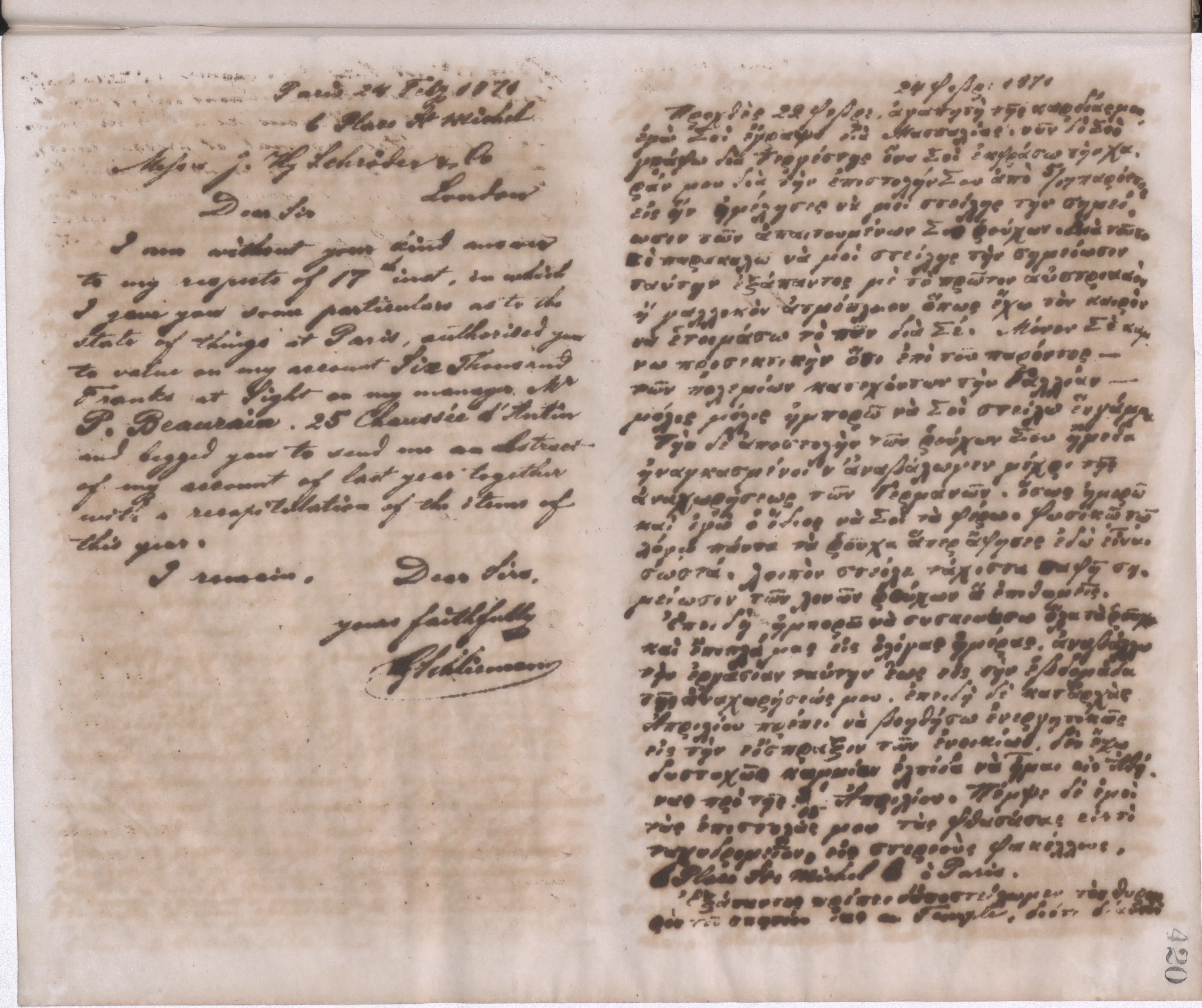

From there, instead of returning to Greece, Schliemann established the pregnant Sophia in Paris, under the superintendence of French and Greek physicians, in order to prevent yet another miscarriage after the many she had undergone after the birth of Andromache. For the following months, up until the birth of Agamemnon in March 1878, Sophia remained alone in Paris with Andromache and the French nanny, with occasional visits from her brother Spyros and, towards the end of her pregnancy, from her mother. Heinrich paid them only one two-day visit, on his way from Würzburg to Athens. He returned to Paris a week before his son's birth on the 16th March 1878

David Traill argues that only a sociopath and egoist like Schliemann could leave his wife alone in a foreign country throughout her pregnancy (Traill 1986). Even Lynn and Gray Poole, authors of One Passion, Two Loves, who painted a very romantic picture of the relationship between Heinrich and Sophia, find Schliemann's behaviour inexplicable.

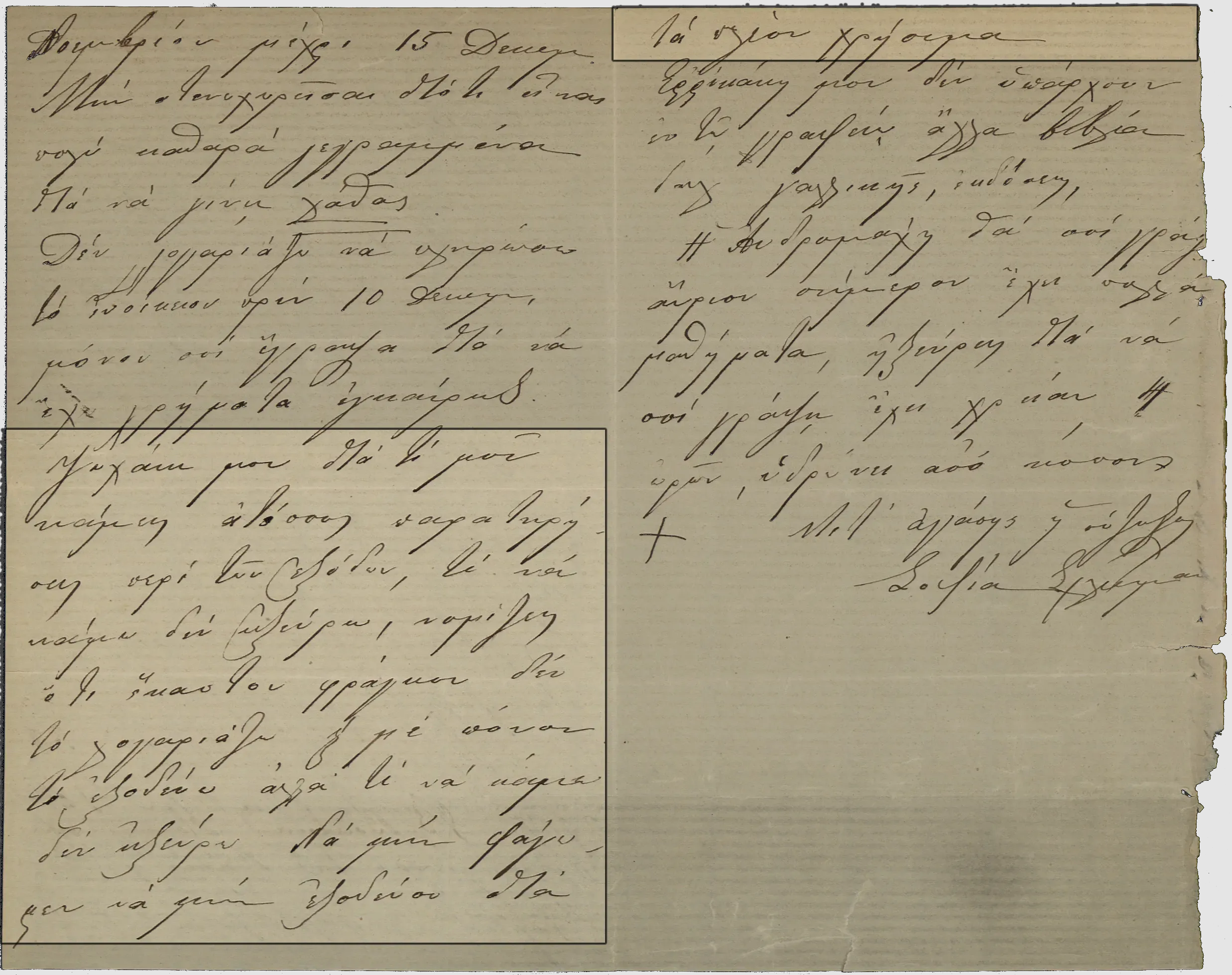

6. SOPHIA REACHES HER LIMITS!

Aside from Heinrich's miserliness, another thorn in their relationship was his insistence on the curative properties of water, whether spas, cold baths or sea-bathing. He himself swam winter and summer. When in Athens he would go every morning on horseback down to Faliron. Even at Troy he never missed the chance of riding to the sea to bathe

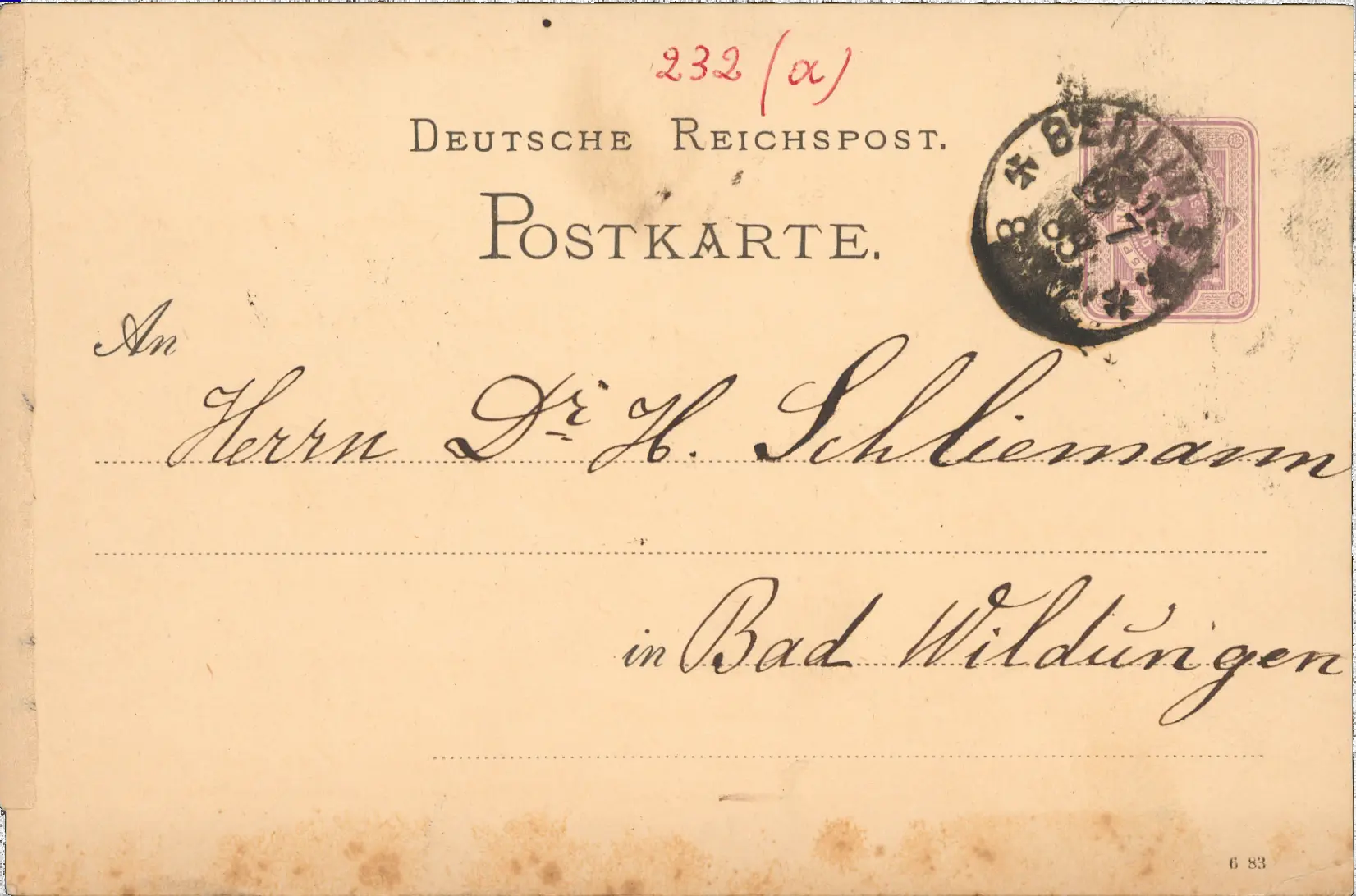

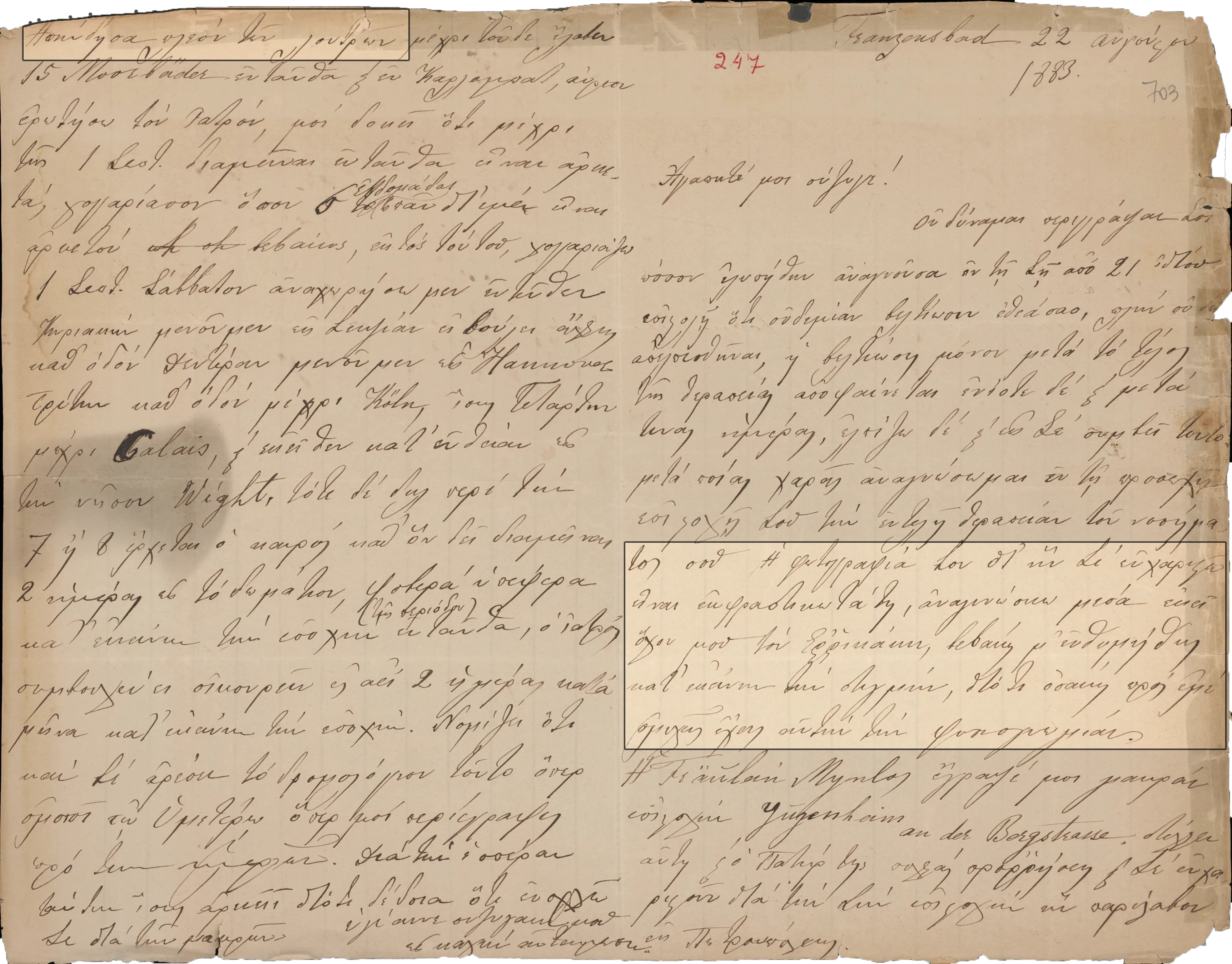

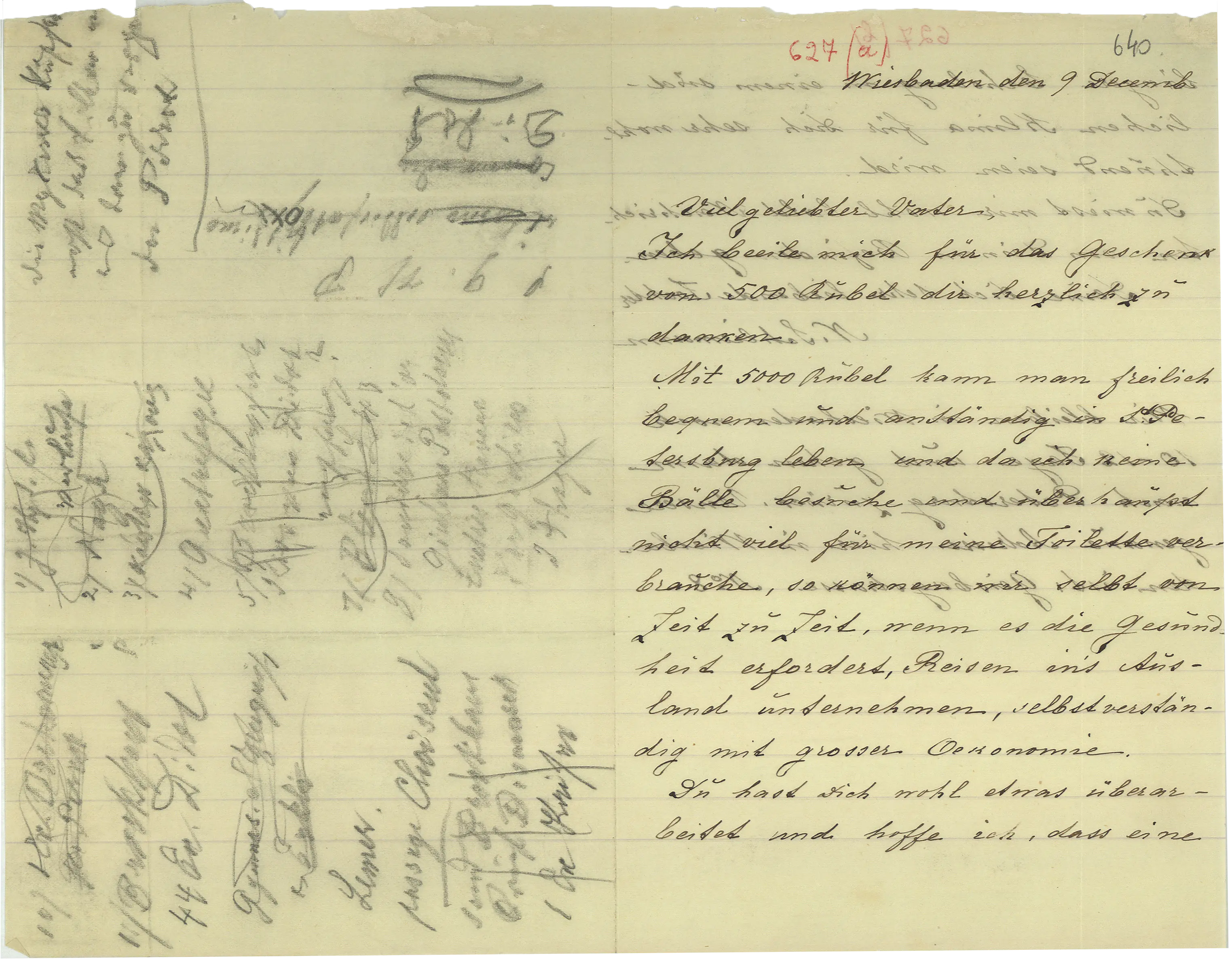

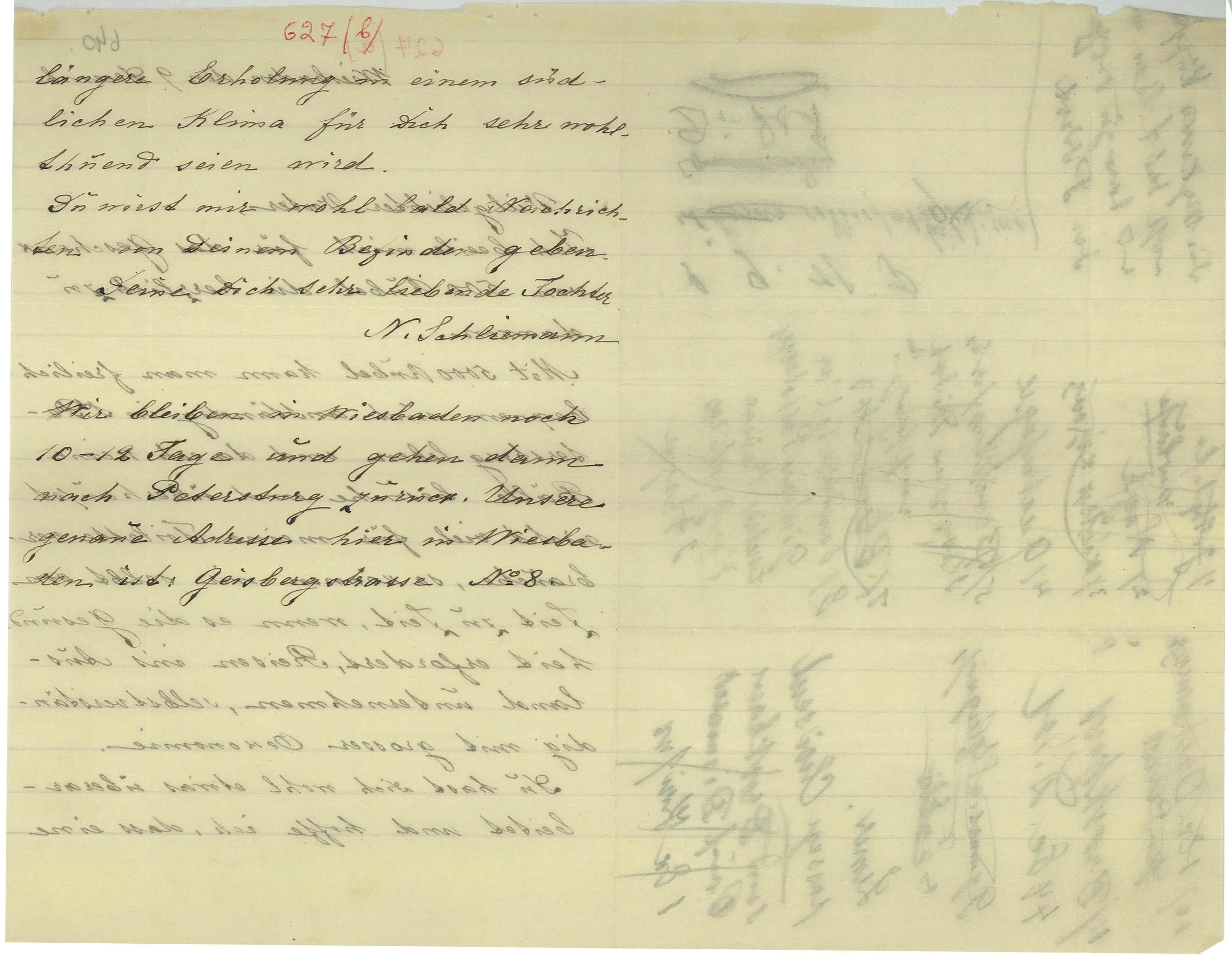

From 1880 the almost obligatory holidays would begin for Sophia and the children at some European spa town in Germany or Austria. Schliemann was usually absent or would take the waters at some other nearby resort, as in the summer of 1883 when he was at Bad Wildungen in Germany while Sophia and the children went to Carlsbad and Franzenbad in Bohemia

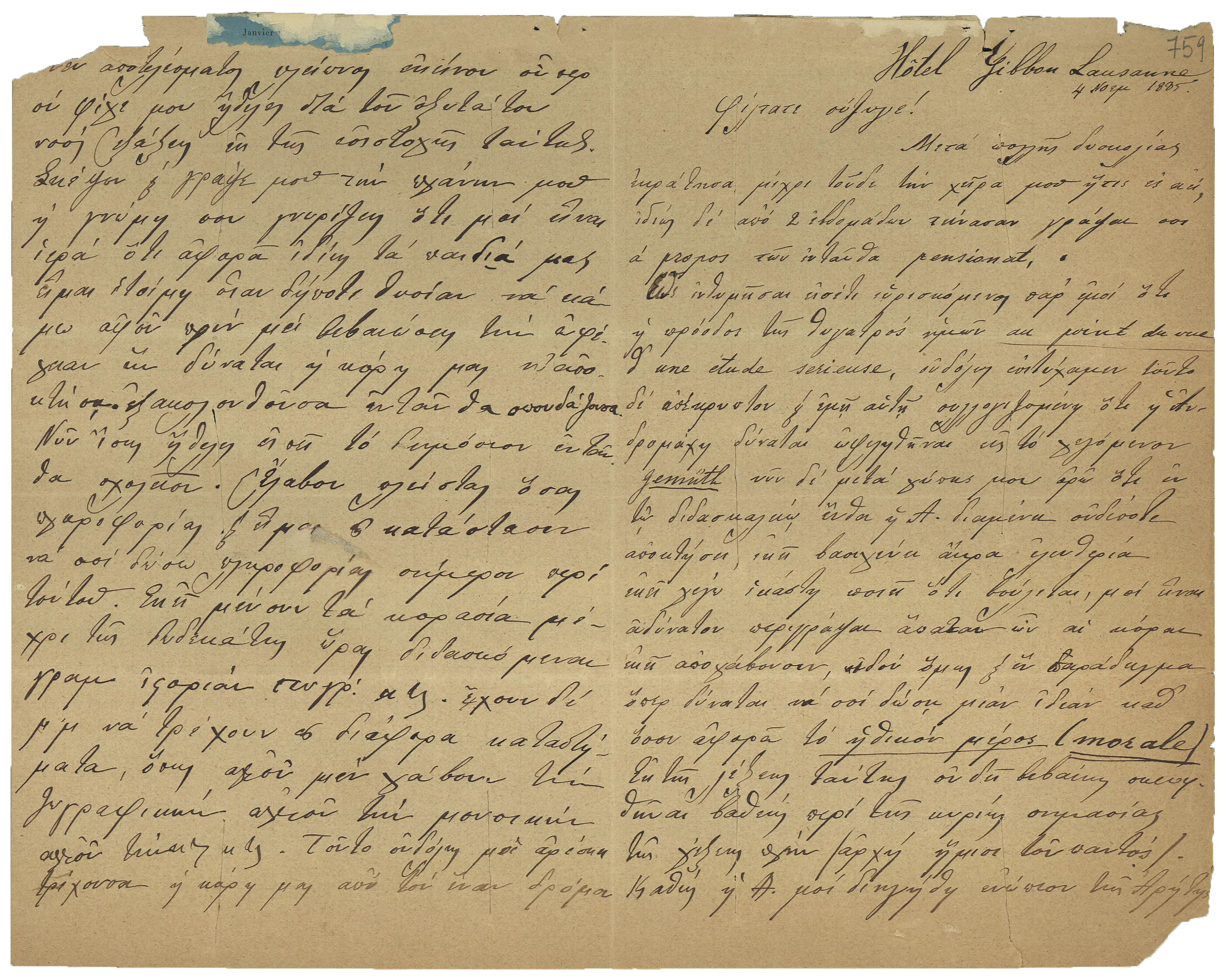

Sophia's most significant revolt happened at the end of 1885, when Schliemann was on holiday in Cuba, and she took it upon herself to make the important decision to cut short Andromache's studies at Lausanne boarding school for girls and return to Athens. Sophia disagreed with the progressive principles of the school. Deep down, it is possible that she could not stand the idea of yet another 'exile' from her beloved Athens.

One year later, at the end of summer 1886, having once more endured the 'exile' of the European spa towns far from the sea she adored, she decided, without his approval, to take the children and go to Ostend on the Belgian coast.

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers.

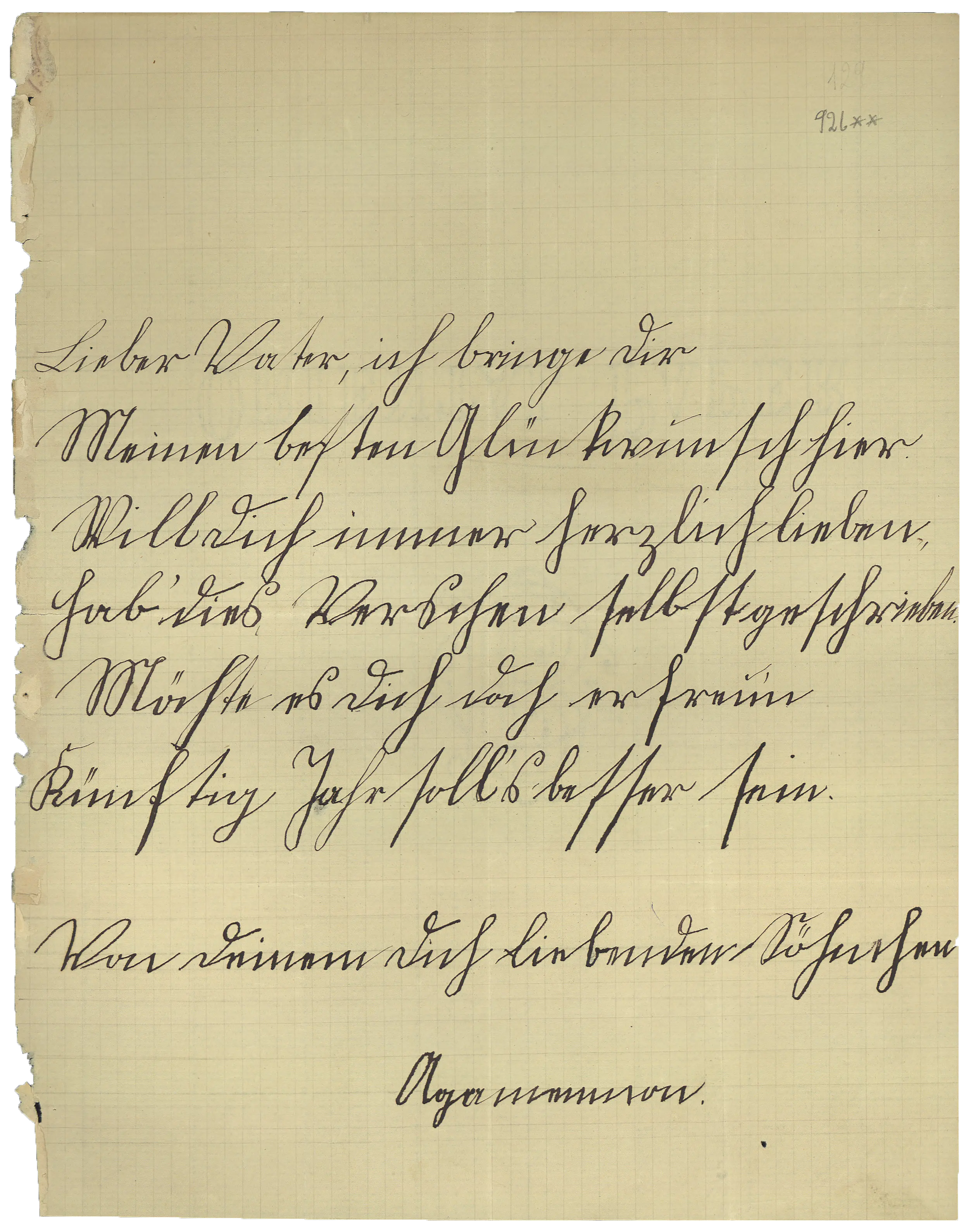

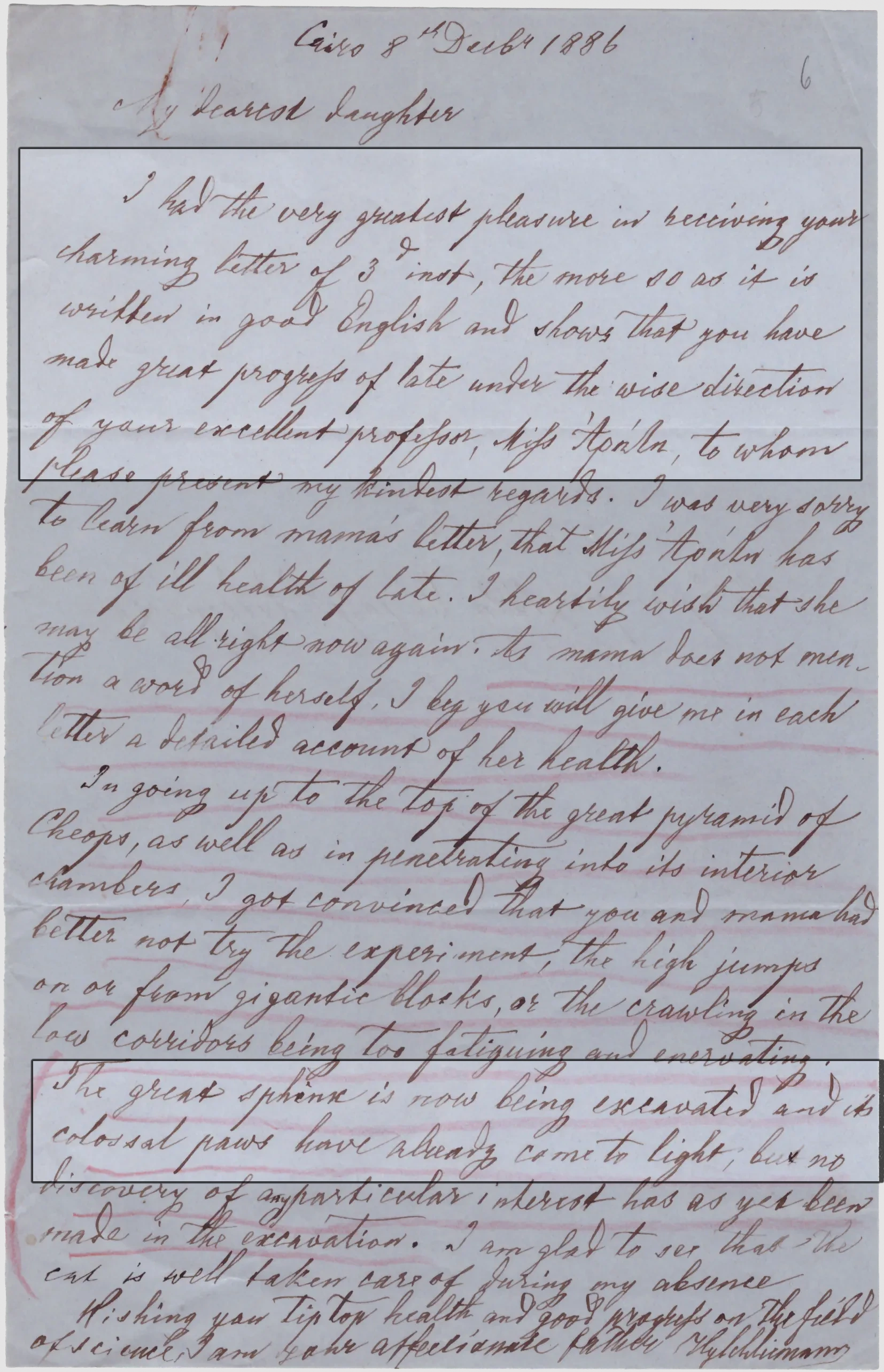

7. 'MY DEAR PAPA'

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers.

With Schliemann absent for long periods, Sophia had the primary role in the upbringing and supervision of their children. In the Heinrich Schliemann Papers there are more letters from Andromache, who was the eldest, and fewer from the younger Agamemnon. Sophia always gave Heinrich news of the children and sometimes made them add one or two lines to her own letters

Schliemann had three children from his first marriage with the Russian Ekaterina Lyschina: Sergei (1855-1939), Natalya (1858-1869) and Nadezhda (1861-1935). Schliemann was on his honeymoon with Sophia when he heard of the death of his daughter Natalya. In a letter to her father Sophia described that painful time: when the news arrived, 'for three days he resembled a dead man'

In the Heinrich Schliemann Papers there are about 115 letters from Nadezhda and 411 from Sergei, which prove that Schliemann maintained close contact with the children of his first marriage. Since most of them, with very few exceptions, are written in Russian, we cannot reach a clear understanding of the relations between them. But it seems that Sophia had a good relationship with Heinrich's children, at any rate with Sergei.

8. WHOM GOD HAS JOINED TOGETHER

The construction of the Iliou Melathron mansion took three years (1878-1880). It was Heinrich's life's dream, but not Sophia's, who was emotionally attached to their first house on Mouson Street. The size and magnificence of the new house reminded her more of a museum than a home.

'...I see that the Fates have healed many of our woes but have also bestowed on us many joys; and as we tend to see the past through rose-coloured spectacles, forgetting its sufferings and recalling only its moments of joy, I cannot praise our marriage sufficiently. For you have never ceased to be for me my beloved wife, a pure-minded companion and trustworthy guide in difficulties, as well as a gentle fellow-traveller and remarkable mother.'

After Heinrich's death, Sophia lived in the Iliou Melathron until 1926, when she moved to Palio Faliro. The Iliou Melathron was for many years a social and intellectual landmark of Athens, with Sophia and her daughter Andromache as gracious hostesses, honoring Schliemann’s legacy.

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Vasilikou, N. 2011. The chronicle of the excavation of Mycenae 1870-1878, Athens

- Daleziou, E. and N. Vogeikoff-Brogan, 2022. The Stuff of Legend: Heinrich Schliemann’s Life and Work. Celebrating the Bicentennial of His Birth (https://schliemannlegend2022.gr/index.php/en/)

- Herrmann, J., E. Maaß, C. Andree, and L. Hallof, c. 1990. Korrespondenz zwischen Heinrich Schliemann und Rudolf Virchow: 1876-1890, Berlin.

- Coulmasi, D. 2006. Schliemann & Sophia: A Love Story, Athens

- Bobou-Protopappa, E. 2005. Sophia Engastromenou-Schliemann: Letters to Heinrich, Athens.

- Trail, D. A. 1986. “Schliemann’s Acquisition of the Helios Metope and his Psychopathic Tendencies,” Myth, Scandal, and History: The Heinrich Schliemann Controversy and a First Edition of the Mycenaean Diary, ed. W. M. Calder III and D. A. Traill, Detroit, 48-80.

- Poole L. and G. 1967. One Passion, Two Loves: The Schliemanns of Troy, London.

- Stager, J. 2022. “Sophia’s double: photography, archaeology, and modern Greece,” Classical Receptions Journal 20, 1–42.

CREDITS

- ORGANIZATION

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives - EXHIBITION CURATORS

Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan

Leda Costaki - EXHIBITION DESIGN

MainSys